By Becca Hall & Kyle Westphal

Twenty years ago, or even ten, the place of home movies within film history and film culture was contested and precarious. Thinking about them was uncomfortable. You remembered posing for the camera, mom rushing into the shot to fix your hair, dad barking directions, your sister rolling her eyes while her camera-less friends enjoyed a real vacation. Even the archivist’s preservation instincts butted up against memories of interminable reels of last summer in Sedona and being held hostage in the den as dad recounted each detail to any passing interloper. Is it so strange that documents of such profound embarrassment and coercion came late to respectability? (At the box office a few weeks ago, a man was looking at the Home Movie Day poster we had on display. “Oh, are you going to come? Do you have any home movies?” His reply: “Looking at those things is always so sad…”)

Twenty years ago, or even ten, the place of home movies within film history and film culture was contested and precarious. Thinking about them was uncomfortable. You remembered posing for the camera, mom rushing into the shot to fix your hair, dad barking directions, your sister rolling her eyes while her camera-less friends enjoyed a real vacation. Even the archivist’s preservation instincts butted up against memories of interminable reels of last summer in Sedona and being held hostage in the den as dad recounted each detail to any passing interloper. Is it so strange that documents of such profound embarrassment and coercion came late to respectability? (At the box office a few weeks ago, a man was looking at the Home Movie Day poster we had on display. “Oh, are you going to come? Do you have any home movies?” His reply: “Looking at those things is always so sad…”)

Yet these films—posed, planned, rehearsed, fussed over, and haphazard nevertheless—often say and show a great deal more than their makers intended. They spur us to recognize the highly social character of our relationships and routines (our whole lives, really) in a distinctive way.

Yet these films—posed, planned, rehearsed, fussed over, and haphazard nevertheless—often say and show a great deal more than their makers intended. They spur us to recognize the highly social character of our relationships and routines (our whole lives, really) in a distinctive way.

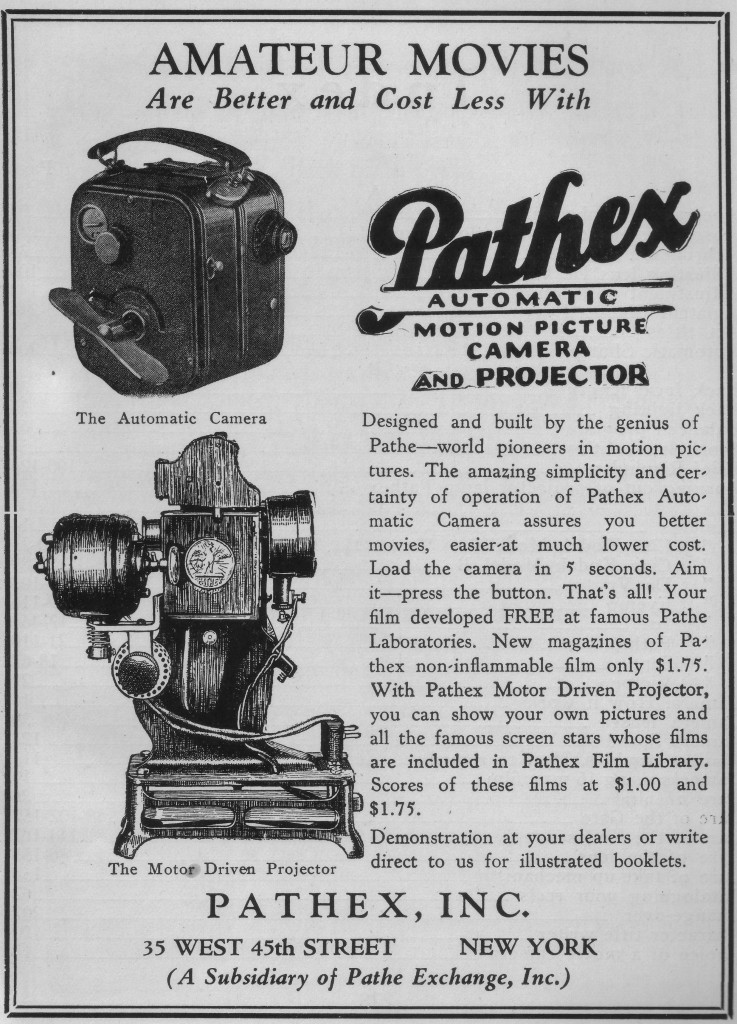

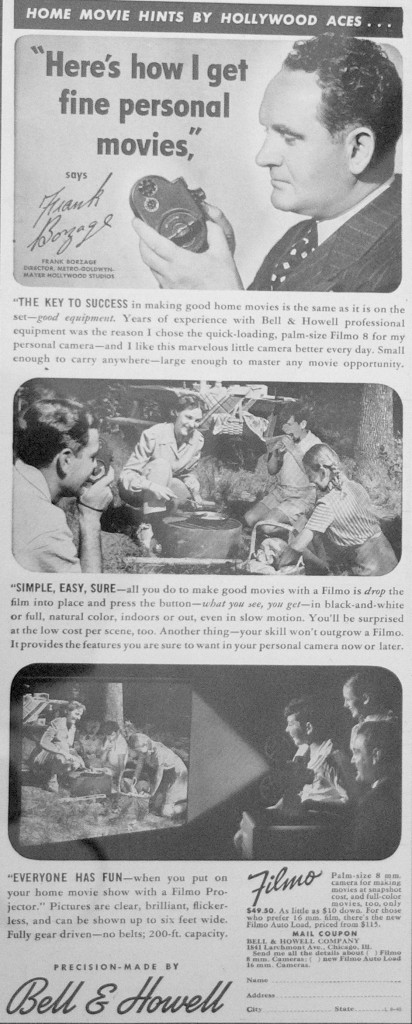

With Home Movie Day fast approaching, it’s easy to take the present stature of these films (itself very much a product of HMD’s laudable successes) for granted. In their heyday, home movie makers reinforced each other’s activities with an array of periodicals and hobbyist clubs–but outside of the insulation of enthusiasm, their type became well known and a frequent target for satire. An early example: in 1939, Robert Benchley made a short for M-G-M, Home Movies, that promised tips for the amateur. As Benchley’s audience falls asleep or gets up to make a telephone call, the cinematographer-editor-projectionist-narrator goes on about using red filters and attributing out-of-focus shots to bad lenses.

Indeed, there was no baser insult than to suggest that a film (Hollywood or otherwise) possessed any resemblance to a home movie. When Pauline Kael wanted to rip 2001: A Space Odyssey, she called it “the biggest amateur movie of them all, complete to the amateur-movie obligatory scene—the director’s little daughter (in curls) telling daddy what kind of present she wants.” Arthur Knight, assuring the readers of the Saturday Review that they needn’t pay much heed to the so-called New American Cinema, invoked more familiar tropes in his review of Dog Star Man: “Brakhage, like so many talented amateurs, has a tendency to fall in love with every frame he shoots. He must find a place for every precious foot, be it overexposed, underexposed, or out of focus.”

Indeed, there was no baser insult than to suggest that a film (Hollywood or otherwise) possessed any resemblance to a home movie. When Pauline Kael wanted to rip 2001: A Space Odyssey, she called it “the biggest amateur movie of them all, complete to the amateur-movie obligatory scene—the director’s little daughter (in curls) telling daddy what kind of present she wants.” Arthur Knight, assuring the readers of the Saturday Review that they needn’t pay much heed to the so-called New American Cinema, invoked more familiar tropes in his review of Dog Star Man: “Brakhage, like so many talented amateurs, has a tendency to fall in love with every frame he shoots. He must find a place for every precious foot, be it overexposed, underexposed, or out of focus.”

In short, if you wanted to convey displeasure with a film—beyond an unsatisfying performance or an unlikely plot twist, but something so unsettling that it rightfully exiled the film from the broader cinema—you invoked those fuzzy 8mm reels and the consummately boring people who made them. In an era when much of America was proudly square, here was an unfortunate figure that even squares could snicker over. Nothing was less compelling than someone else’s family memories.

was an unfortunate figure that even squares could snicker over. Nothing was less compelling than someone else’s family memories.

It’s relevant, then, that Home Movie Day was instigated by a generation that came of age in the twilight of the form, or afterwards. Nowadays we get together one Saturday every October—International Home Movie Day—and pore over other people’s reels. Many of us are young enough to have grown up with no filmed record of our own lives. We don’t have baggage around home movies, nor, on the other hand, a nostalgic yearning for a magically resurrected past (we never lived in it).

What we do have is a materialist consciousness about history. While local HMD organizers often offer tips about where and how to transfer old films to DVD, the emphasis is on screening the films themselves in their original state. Often, curious community members will traipse in with a box of Super 8; there might be a projector in the attic and it probably doesn’t work, or at least, I tried to turn it on once and I think it sparked. Is it supposed to do that?

From this point of view, a part of the value of looking at old home movies is that they reacquaint us with our machine selves. We marvel at a sizable portion of the public threading cameras, choosing lenses, and splicing bits and pieces with an ease that seems very remote now, even and especially for those who make their livings through video editing. Our amateur grandparents really did all this?

But the physical fascination goes beyond this—even divorced from their Bolexes and Bell & Howells, the films themselves carry an attraction. They were recorded on film stocks with distinctive characteristics that enlarge and make solid their subjects. One can be totally uninterested in a stranger’s fishing expedition or a periwinkle birthday party or in any of the feelings or aspirations that originally made those subjects worth recording to the people who picked up the camera – but fascinated by the form they inhabit on screen, the beautifully refined grain of a b&w reversal or the vivid saturation of a Kodachrome reel. (It is ironic—and perhaps just—that Kodachrome maintains its brilliant color today while contemporaneous big-budget Hollywood features have faded to magenta mush.)

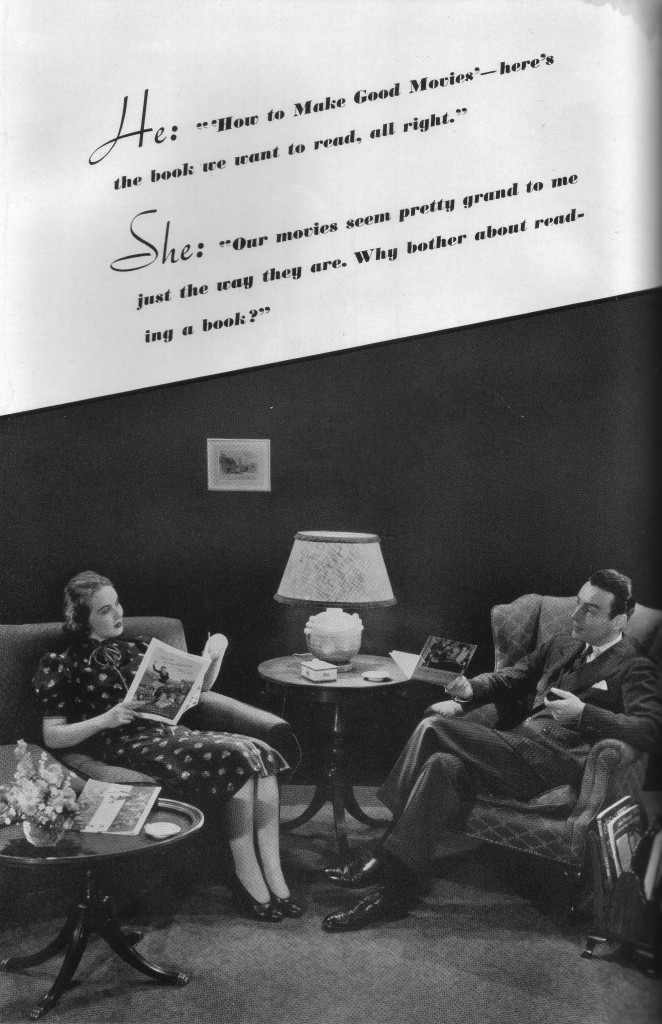

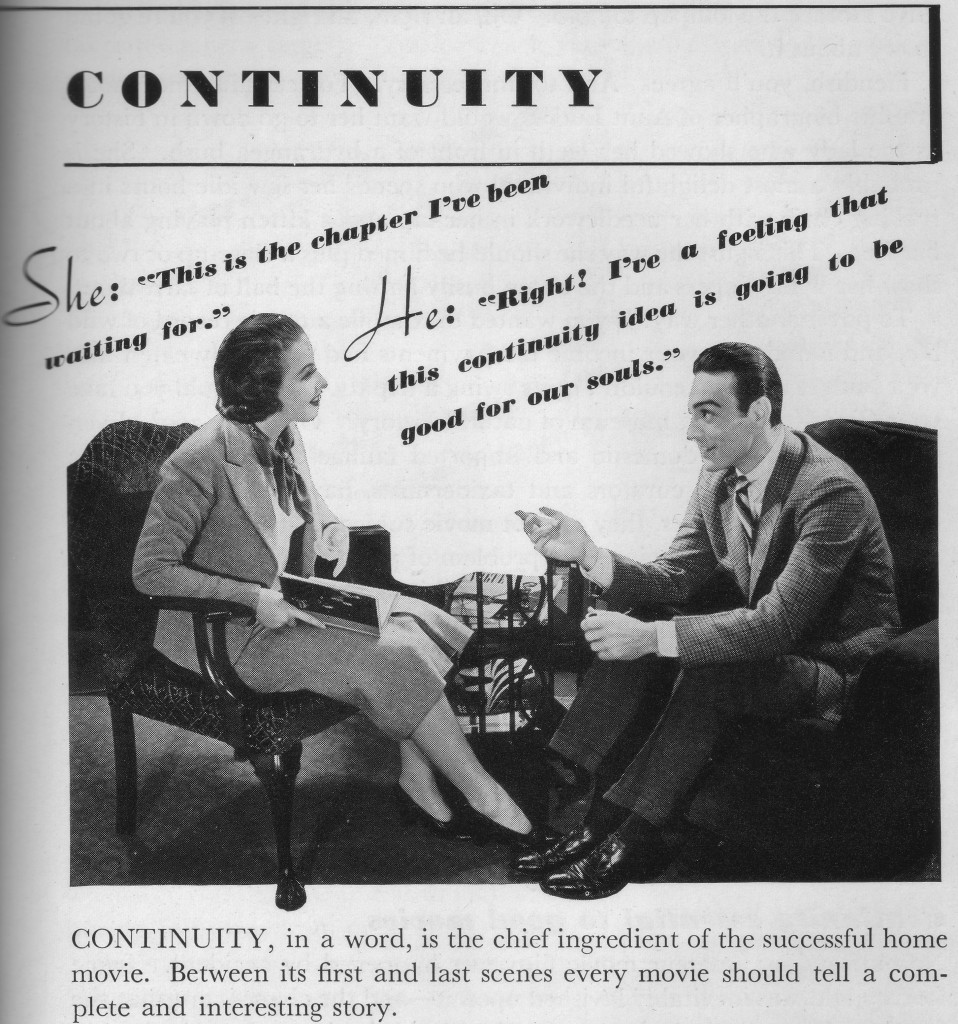

As Patricia Zimmerman has exhaustively documented in her book Reel Families, the literature directed at home movie makers was endlessly prescriptive, continuity-orientated, and generally imitative of Hollywood values. (Some pages from Kodak’s How to Make Good Movies, circa 1950, serve as illustrations throughout this post.) But the experience of watching home movies does not demonstrate these lessons. The practical challenges of working with non-professional equipment often dictated something quite different. The relatively brief recording times afforded by the size of small-gauge camera rolls and magazines necessitated a precious and considered style of shooting. No one wanted to waste footage, and few had the patience to edit it later. Rapid cuts and brutal changes of scenery in amateur productions abound. (Watch enough home movies and the technique looks closer and closer to avant-garde cinema.) The camera would glimpse something for a few seconds at a time, or maybe a few frames. The ecstatic accretion of landscapes, character sketches, familiar buildings, adorable animals, life’s milestones, and mundane incidents genuinely reflected the unordered psychic life of the amateur cameraman (or woman). It’s personal expression shaped by essentially material considerations of the medium.

As Patricia Zimmerman has exhaustively documented in her book Reel Families, the literature directed at home movie makers was endlessly prescriptive, continuity-orientated, and generally imitative of Hollywood values. (Some pages from Kodak’s How to Make Good Movies, circa 1950, serve as illustrations throughout this post.) But the experience of watching home movies does not demonstrate these lessons. The practical challenges of working with non-professional equipment often dictated something quite different. The relatively brief recording times afforded by the size of small-gauge camera rolls and magazines necessitated a precious and considered style of shooting. No one wanted to waste footage, and few had the patience to edit it later. Rapid cuts and brutal changes of scenery in amateur productions abound. (Watch enough home movies and the technique looks closer and closer to avant-garde cinema.) The camera would glimpse something for a few seconds at a time, or maybe a few frames. The ecstatic accretion of landscapes, character sketches, familiar buildings, adorable animals, life’s milestones, and mundane incidents genuinely reflected the unordered psychic life of the amateur cameraman (or woman). It’s personal expression shaped by essentially material considerations of the medium.

The aspects of home movies that irritated acquaintances and supplied fodder for caricatures seem especially notable, even radical, today–not least the naturally social aspects of their exhibition. Home movies (and their kissing cousin, the slide carousel) were screened privately, between friends, often with narration. (The wide diffusion of Super 8 equipped with recordable magnetic soundtracks allowed the amateur to preserve this narration on the film strip itself, along with other supplemental audio. Kodak even issued an LP of music and sound effects tailor-made for this purpose.) Home movies were not flung to the wind or leveraged for amorphous recognition. They were shared purposefully in a frankly intimate way that necessarily affirmed the communal underpinnings of experience. Talk about social media. For those of us whose lives and interactions have been mediated more by Facebook and the internet than by Kodak and the living room, the levels of sustained mutual interest – genuine or not – involved in such presentations is almost unimaginable. Home Movie Day becomes a way of attempting to imagine our lives without the need for privacy settings or “like” buttons.

The aspects of home movies that irritated acquaintances and supplied fodder for caricatures seem especially notable, even radical, today–not least the naturally social aspects of their exhibition. Home movies (and their kissing cousin, the slide carousel) were screened privately, between friends, often with narration. (The wide diffusion of Super 8 equipped with recordable magnetic soundtracks allowed the amateur to preserve this narration on the film strip itself, along with other supplemental audio. Kodak even issued an LP of music and sound effects tailor-made for this purpose.) Home movies were not flung to the wind or leveraged for amorphous recognition. They were shared purposefully in a frankly intimate way that necessarily affirmed the communal underpinnings of experience. Talk about social media. For those of us whose lives and interactions have been mediated more by Facebook and the internet than by Kodak and the living room, the levels of sustained mutual interest – genuine or not – involved in such presentations is almost unimaginable. Home Movie Day becomes a way of attempting to imagine our lives without the need for privacy settings or “like” buttons.

• • •

We haven’t reckoned entirely with the whole phenomenon of home cinema yet. Often lacking titles, credits, stories, genres, and precise dates, home movies upset our traditional habits of criticism and cataloging. In the list-obsessed milieu of film culture, we emphasize fully achieved, ornately constructed masterpieces; how can a nameless hundred-foot stretch about cows compete? It’s easier to get grant money for preserving local landmarks than you might think (you should try it!), but the difficult work required to assure its circulation and exhibition is too often an afterthought. Home movies record real people in real places–and deserve real dissemination rather than virtual real estate on YouTube.

We haven’t reckoned entirely with the whole phenomenon of home cinema yet. Often lacking titles, credits, stories, genres, and precise dates, home movies upset our traditional habits of criticism and cataloging. In the list-obsessed milieu of film culture, we emphasize fully achieved, ornately constructed masterpieces; how can a nameless hundred-foot stretch about cows compete? It’s easier to get grant money for preserving local landmarks than you might think (you should try it!), but the difficult work required to assure its circulation and exhibition is too often an afterthought. Home movies record real people in real places–and deserve real dissemination rather than virtual real estate on YouTube.

Archival consciousness about the value of home movies has been raised in recent years, but there are still pockets of resistance. As late as 2006, The Advanced Projection Manual (a publication of the International Federation of Film Archives, no less!) explicitly denigrated small-gauge filmmaking and strongly advised against its exhibition in cinémathèques. A snide caption reminded readers of ‘Narrow gauge projection in its appropriate context’—a squirrelly-looking boy unspooling a reel by hand. (Needless to say, much more than home movies are swept up in this dismissal of small-gauge cinema; the layout of The Advanced Projection Manual pointedly lavishes attention on the relative handful of 3-D and 70mm productions while ignoring mountains of experimental films, educational reels, sponsored shorts, and Scopitones that populate the substandard field.)

One hopes that such a sentiment would be politically indefensible today. Still, if home movies are henceforth found in archives rather than in living rooms —if they’re to be more than just a plentiful source of stock footage for mediocre television documentaries—we must engage and exhibit them. The social horizon that bred home cinema is gone, but Home Movie Day—the resurrection, affirmation, and expansion of its spirit—only grows.