Who says there are no more frontiers?

Who says there are no more frontiers?

When movie trade magazine Boxoffice asked this question in January 1954, they were referring, of course, to a new independent production in the wilds of Kansas City, Missouri. A celebration of ‘Corn and Youth,’ this new film was the product of a band of amateurs ‘pioneering in feature production … and loving it.’

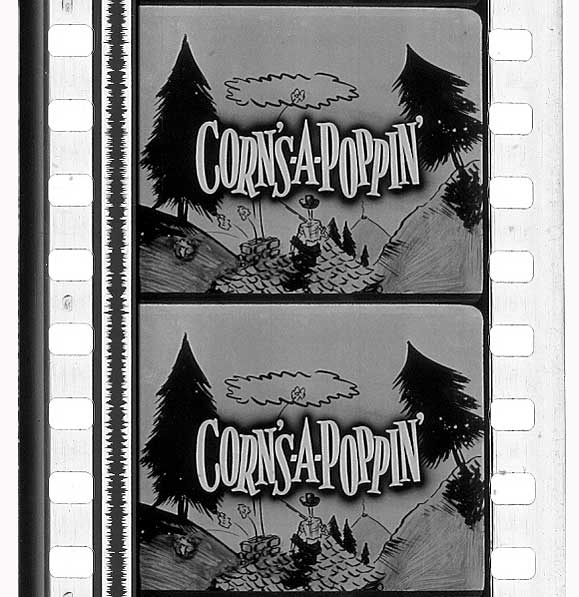

The financing had been set up by Elmer Rhoden, Jr., an executive for the Commonwealth Theatres chain, which controlled several dozen screens in six states. Show business ran in the family. His father Elmer C. Rhoden spent four decades with National Theatres and was elected its president after 20th Century-Fox’s court-ordered divestment from the chain. Brother Clark Rhoden was chairman of the Popcorn Institute, a kernel-pushing trade group. Thus the production’s shift from working title Ozark Hoedown to the more industry- and exploitation-friendly Corn’s-a-Poppin’.

To come upon Corn’s-a-Poppin’ today is to glimpse another frontier—a frontier made legible by recent shifts in the archival field. Situated at the woozy (and suddenly respectable) intersection of regional cinema, orphan media, and sponsored film, Corn’s-a-Poppin’ is an expansive aberration. Never self-important enough to suggest itself as a ‘key text,’ Corn’s-a-Poppin’ nevertheless emerges to exemplify a certain kind of unaccountable film. Its production and existence still sound like a fanciful rumor, even after you’ve seen it.

The Altman Connection?

Distractingly, Robert Altman is credited as co-screenwriter. Some, including anonymous contributors to the Internet Movie Database, upgrade his involvement to co-director. This is ironic, given that Altman disowned the film and requested that any surviving copies be destroyed. It’s not much discussed in the expanding body of Altman literature, though one biographer, Patrick McGilligan, does name a chapter after it, but only to mock the film and use its title as obviously-absurd har-har shorthand for a particularly fallow period in Altman’s career. You can’t get any lower than a picture called Corn’s-a-Poppin’, right?

A rabid auteurist might stretch the connection and claim Corn’s-a-Poppin’ as a clear antecedent to Nashville or The Prairie Home Companion, as all three share a vaguely similar down home milieu. But this suggests a clear line of personal development—and one that leads quickly, conveniently, and inexorably away from Corn’s-a-Poppin’—rather than the messier, and inherently collective, mystery of the film itself.

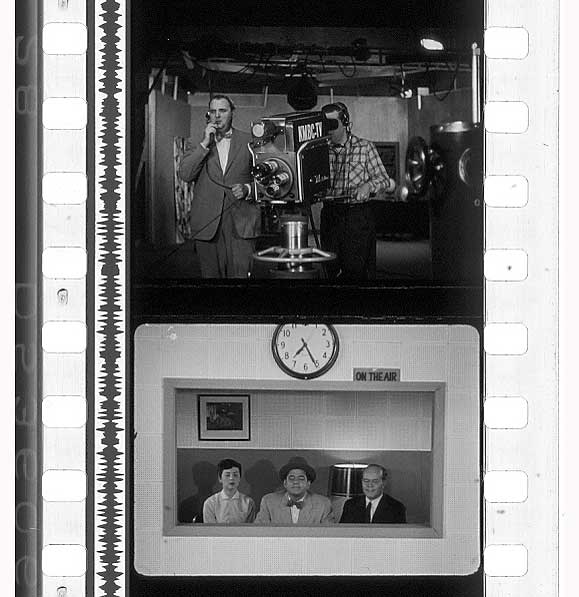

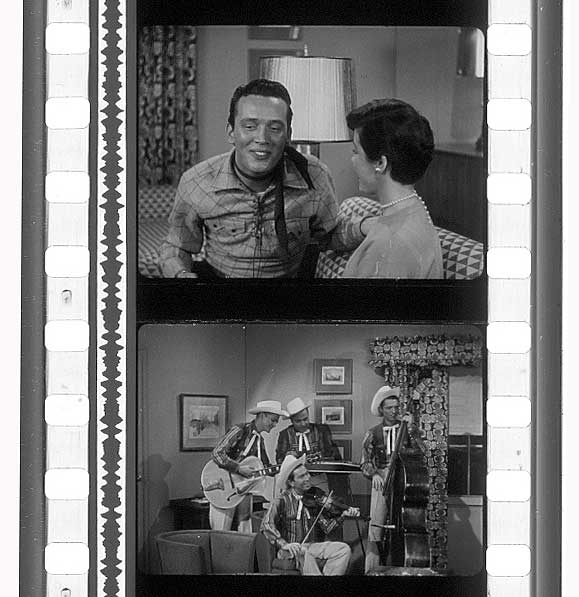

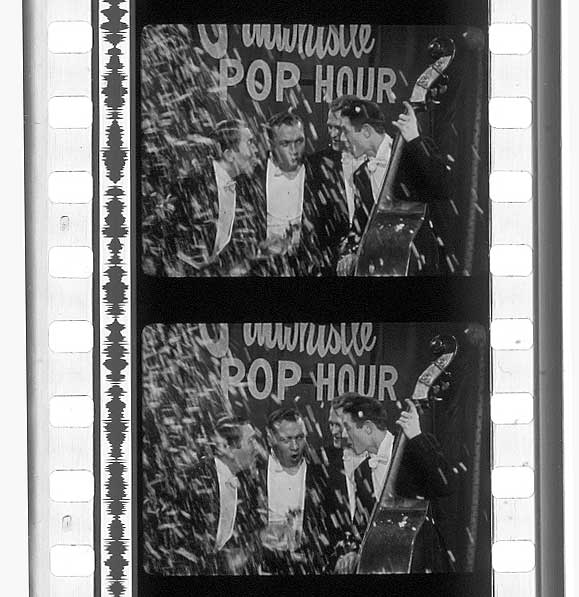

On its own, Corn’s-a-Poppin’ is a beguiling experience. Few films have seemed prouder of their low-rent constraints. The sets are dressed-down television leftovers, which is actually appropriate, as the plot revolves around the trials of producing an inept program called The Pinwhistle Popcorn Hour. The show, a wild scheme hatched by marketing man Waldo Crummit (James Lantz) to boost sales for Thaddeus J. Pinwhistle (Keith Painton) hovers between an embarrassment and outright sabotage. In the first reel Waldo introduces Pinwhistle to his newest headliner, former hog-caller Lillian Gravelguard (Nora Lee Benedict) whose rendition of “Drink Only to Me” actually makes the anemic popcorn seem the rightful highlight of the program. Just about the only positive effect of this enterprise is the flirtatious manner affected by Pinwhistle’s “more-than-a-secretary” secretary Sheila (Pat McReynolds) and folksy Pinwhistle Popcorn Hour announcer Johnny Wilson (Jerry Wallace), whose charm helps viewers to forget that the show only runs half an hour. The only obstacle to their union is Johnny’s pushy kid sister Susie (Little Cora Rice) who orders him around like hen-pecking wife and airs her opinions about his TV show with minimal tact. Susie speaks with all the bluster and toughness of a boozed-out Hollywood sideshow, cooks all of Johnny’s meals in an apron, and possesses a disposition very unbecoming of a child star.

On its own, Corn’s-a-Poppin’ is a beguiling experience. Few films have seemed prouder of their low-rent constraints. The sets are dressed-down television leftovers, which is actually appropriate, as the plot revolves around the trials of producing an inept program called The Pinwhistle Popcorn Hour. The show, a wild scheme hatched by marketing man Waldo Crummit (James Lantz) to boost sales for Thaddeus J. Pinwhistle (Keith Painton) hovers between an embarrassment and outright sabotage. In the first reel Waldo introduces Pinwhistle to his newest headliner, former hog-caller Lillian Gravelguard (Nora Lee Benedict) whose rendition of “Drink Only to Me” actually makes the anemic popcorn seem the rightful highlight of the program. Just about the only positive effect of this enterprise is the flirtatious manner affected by Pinwhistle’s “more-than-a-secretary” secretary Sheila (Pat McReynolds) and folksy Pinwhistle Popcorn Hour announcer Johnny Wilson (Jerry Wallace), whose charm helps viewers to forget that the show only runs half an hour. The only obstacle to their union is Johnny’s pushy kid sister Susie (Little Cora Rice) who orders him around like hen-pecking wife and airs her opinions about his TV show with minimal tact. Susie speaks with all the bluster and toughness of a boozed-out Hollywood sideshow, cooks all of Johnny’s meals in an apron, and possesses a disposition very unbecoming of a child star.

Part of what makes Corn’s-a-Poppin’ so unaccountable is the way it moves effortlessly between studied sarcasm and stiff line readings. Waldo Crummit seems like a creation shoplifted from a Frank Tashlin comedy—a vulgar showbiz mover who profits in proportion to the talent’s bust. When Pinwhistle finds Crummit making a deal with an executive at Chicago’s Crinkly Corn, Crummit deploys some improbable hooey about negotiating with a senator. We’re clearly meant to take Crummit’s listless recitation as a bad joke. Likewise when he insists that the vocal talents of Miss Gravelguard are not a danger to Pinwhistle or his popcorn, reasoning that his business is about corn, not critics. Or when he laments a strain of ‘vocal cord-itis.’ These are lousy one-liners and lame locutions infused with a consciously pathetic air. Much in the same manner, Gravelguard’s singing is meant to be bad, horrendous, an ongoing train wreck of a thing. She becomes the butt and embodiment of a familiar joke about no-talent floozies crooning through a sea of cheap whiskey tears.

The performances are all over the map. How are we to reconcile the knowing dumbness of James Lantz’s performance and the near-documentary coyness of Pat McReynolds and Jerry Wallace? Keith Painton screams all his lines into an intercom, frets while twirling his girly fisticuffs, and always dances on the line of being hip to the whole ploy but never quite crosses it.

The performances are all over the map. How are we to reconcile the knowing dumbness of James Lantz’s performance and the near-documentary coyness of Pat McReynolds and Jerry Wallace? Keith Painton screams all his lines into an intercom, frets while twirling his girly fisticuffs, and always dances on the line of being hip to the whole ploy but never quite crosses it.

Satirically speaking, the main targets of Corn’s-a-Poppin’ are amateur ambition, outsized egos, outrageous shysterism. Yet all these qualities are abundantly present in the film, too. If the Pinwhistle Popcorn Hour is supposed to be a pathetic outpost for fifth-rank talent—horrible enough to wreck the whole popcorn empire—then what does that make Corn’s-a-Poppin’? Even rowdy crowds in the back row intuit the silliness (and limited promotional value) of pelting musicians with popcorn during a set.

And yet, the characterizations are so insistent that they overwhelm the material. After seeing Corn’s-a-Poppin’, you may find yourself referring to someone as ‘a real Waldo Crummit.’ If only more people could see this film, the name might enter the cultural lexicon and take on a real Dickensian largess. It’s such a useful and illustrative shorthand—a spot-on accurate rendition of a certain kind of marketing sensibility that has made so many of our relationships stilted and false. There’s a lesson here.

Out of This World

Evan Chung, one of the earliest advocates of Corn’s-a-Poppin’, tipped his hat to James Agee and nominated it a plausible candidate for ‘the godamndest thing ever seen.’ Writing about Corn’s-a-Poppin’ and a body of related films, he offered a compelling entry point for novices: “The immediate conclusion a viewer may draw after seeing these movies is that they are not manmade at all, but are some sort of alien artifact – a parody of cinema made by some distant race with only vague familiarity with human and filmic conventions.”

Evan Chung, one of the earliest advocates of Corn’s-a-Poppin’, tipped his hat to James Agee and nominated it a plausible candidate for ‘the godamndest thing ever seen.’ Writing about Corn’s-a-Poppin’ and a body of related films, he offered a compelling entry point for novices: “The immediate conclusion a viewer may draw after seeing these movies is that they are not manmade at all, but are some sort of alien artifact – a parody of cinema made by some distant race with only vague familiarity with human and filmic conventions.”

Indeed, the first impulse when looking at a film like Corn’s-a-Poppin’ is to say it lies beyond terrestrial film history. Some sources date Corn’s-A-Poppin’ to 1951, others to 1956. The studious compilers of the AFI Catalog of American Feature Films admit that trade sources betray little about its production and that it would be presumptuous to assume that the film was ever exhibited in commercial cinemas at all.

A little detective work goes a long way. The 1951 date is clearly specious, though oft cited in Altman filmographies; the lyrics of the climatic number “On Our Way to Mars” make explicit reference to Cinemascope (about which more later), which was not commercially exhibited until late 1953. No copyright was ever registered for the film, though a surviving one-sheet distributed though National Screen Service carries a 1955 tag.

As it turns out, Corn’s-a-Poppin’ is manmade and contains within it several strands of regional history. The figure of the popcorn mogul was particularly close to home. Kansas Citian Charles T. Manley was the real Pinwhistle, a true innovator whose electrical popper assured popcorn’s passage from fairground snack to movie theater staple. Manley’s building (now a condominium dubbed the Popcorn Lofts) dominated the four-square-block Film Row, the Midwest distribution beachhead for Hollywood features.

Though Manley had been dead since 1946, his shadow loomed large. A 1949 profile in the Saturday Evening Post began:

Two substantial delegates to a manufacturers’ convention stood at the bar of a St. Louis hotel a few years ago.

“What’s your line,” one asked.

“Popcorn,” said the other, and handed over a card. “Manley, Inc.,” it said. “The Biggest Name in Popcorn. Charles T. Manley, president.”

“Believe it or not,” he remarked confidentially, “the popcorn business isn’t peanuts.”

It’s the kind of bluster that would fit comfortably in Corn’s-a-Poppin’. Could Waldo Crummit’s plan to liquidate Pinwhistle and pay “peanuts for popcorn” be just a coincidence? A photograph featuring the junior Manley hobnobbing with Wallace, Woodburn, and Rhoden on the set strongly suggests the Pinwhistle character was meant as an affectionate tribute to a local legend.

Kansas City was also a hub of industrial filmmaking, home as it was to the Calvin Company, the Midwest’s biggest and most innovative sponsored film shop. Many Corn’s-a-Poppin’ personnel cut their teeth with Calvin, including Altman, Woodburn, Lantz, and Painton. (Painton is a featured player in Murder on the Screen, the 1958 responsible-film-handling educational short commissioned by Eastman-Kodak that may well be Calvin’s masterpiece.)

And yet Corn’s-a-Poppin’ doesn’t look like a Calvin film. It’s more slash-dash than stylish. Despite Woodburn’s TV work (two years making TV movies, one year as manager at Chicago’s WBKB), it doesn’t look like TV either, seemingly ignorant of the multi-camera shooting style then becoming dominant. The closest cousins of Corn’s-a-Poppin’ are probably the hopelessly anonymous soundies of the 1940s, equally unaffected by the temptation of directorial invention. Most of the scenes in Corn’s-a-Poppin’ are one-take wonders, sometimes spoiled by an unexpected cut-in. The lighting is of the lowest possible quality: while the figures are always intelligible, shadows begin to converge whenever a performer walks towards the corner of a room. The act of opening a door becomes a kaleidoscopic moment when the set is lit with half a dozen stray fill-lights.

And yet Corn’s-a-Poppin’ doesn’t look like a Calvin film. It’s more slash-dash than stylish. Despite Woodburn’s TV work (two years making TV movies, one year as manager at Chicago’s WBKB), it doesn’t look like TV either, seemingly ignorant of the multi-camera shooting style then becoming dominant. The closest cousins of Corn’s-a-Poppin’ are probably the hopelessly anonymous soundies of the 1940s, equally unaffected by the temptation of directorial invention. Most of the scenes in Corn’s-a-Poppin’ are one-take wonders, sometimes spoiled by an unexpected cut-in. The lighting is of the lowest possible quality: while the figures are always intelligible, shadows begin to converge whenever a performer walks towards the corner of a room. The act of opening a door becomes a kaleidoscopic moment when the set is lit with half a dozen stray fill-lights.

History on Cinemascope

Gone from prints today is any suggestion that Corn’s-a-Poppin’ was shot in color. Boxoffice initially reported Anscocolor photography and a pleasing Film Row preview of the color rushes. What happened between shooting and release remains a mystery.

The intended aspect ratio is also a puzzle. The credits, which fill the frame from top to bottom, imply 1.37:1. But the balance of the feature is curiously unbalanced. Common practice would have the cinematographer (also Woodburn in this case) shooting with the assumption that exhibitors would crop the picture anywhere from 1.66:1 to 2:1 depending on their situation. Most films shot to accommodate varying exhibition ratios center all the action in the frame, leaving dead air at the top and bottom that a projectionist could chop off without any dramaturgical loss. Not so with Corn’s-a-Poppin’, where the characters hover towards the bottom half of the frame, leaving empty spaces (bare walls, kitchen cabinets, windows looking out on nowhere) in the upper half. No combination of lenses and aperture plates can disguise Corn’s-a-Poppin’ as a conventional film. It’s touching, actually; these kids wanted to jump on the widescreen band wagon but their combined experience in 16mm and TV filmmaking did not prepare them for the technical niceties of it.

The intended aspect ratio is also a puzzle. The credits, which fill the frame from top to bottom, imply 1.37:1. But the balance of the feature is curiously unbalanced. Common practice would have the cinematographer (also Woodburn in this case) shooting with the assumption that exhibitors would crop the picture anywhere from 1.66:1 to 2:1 depending on their situation. Most films shot to accommodate varying exhibition ratios center all the action in the frame, leaving dead air at the top and bottom that a projectionist could chop off without any dramaturgical loss. Not so with Corn’s-a-Poppin’, where the characters hover towards the bottom half of the frame, leaving empty spaces (bare walls, kitchen cabinets, windows looking out on nowhere) in the upper half. No combination of lenses and aperture plates can disguise Corn’s-a-Poppin’ as a conventional film. It’s touching, actually; these kids wanted to jump on the widescreen band wagon but their combined experience in 16mm and TV filmmaking did not prepare them for the technical niceties of it.

The aspect ratio question is of more than technical interest. It’s a linchpin of the emotional experience. In the midst of the penultimate number, “On Our Way to Mars”—a piece of minimalist s-f with Susie and Johnny floating in a cardboard rocket ship while crooning about finding a grilled cheese sandwich on the moon—Little Cora Rice declares, “We’ll make history on CinemaScope!” If only! Its actors will never see their names on a marquee or headline a Hollywood production. The reference to unattainable aesthetic luxuries has the effect of reminding us that Corn’s-a-Poppin’ constitutes a wooly alternative to them.

Aficionados of Corn’s-a-Poppin’ have faced several challenges, not least the assumption that affection for the film is rooted in a taste for camp and ‘so bad it’s good’ cheese. More fundamentally, the film is presently available only in original 35mm release prints, scattered between public and private hands. Suffice it to say, it’s never been released on home video. The original negative was destroyed years ago and proselytizing for the Corn’s-a-Poppin’ cause entails exhuming these fragile prints and coaxing them through a projector. Balancing our enthusiasm for Corn’s-a-Poppin’ with our responsibility to save it for posterity has always been difficult.

We have recently acquired a very good 35mm print of Corn’s-a-Poppin’—very likely the best one still extant—and we’ll be screening it once at Cinema Borealis before putting it on lockdown for preservation. If you find yourself singing along with “Running After Love,” please consider donating to the cause.