Short subjects never get enough credit. (We’re the only venue in Chicago that shows them regularly.) We like this week’s feature, Of Human Bondage, quite a bit, but “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter,” the short that will be accompanying it, is even better. – Ed.

Can a cartoon also be a documentary?

Can a cartoon also be a documentary?

It’s common enough to hear a fiction feature acclaimed for its so-called documentary qualities—ragged streets or bumpy camerawork, grubby, unshaven performers and the like. In other words, unpolished and unprofessional, but for solid, condescendingly proletarian reasons. (See, among other things, Call Northside 777, Panic in the Streets, and the rash of dreary semi-documentary procedurals popular in the late forties and early fifties.)

There’s certainly a documentary value in many narrative films of the past, but rarely for conscious reasons. It comes across in the storefronts and backrooms—details judged too unimportant to retouch and smooth out. Some aspects of everyday life simply rated too unconscious to fictionalize, too second-nature to fake.

Cartoons would seem to lack this possibility—everything is drawn out on the page, never simply photographed. One thinks instead of the heroic animated journalism of Winsor McCay and his imagined account of “The Sinking of the Lusitania” of 1918—a frenzied, conscientious recreation of the present down to its every rivet. A flip-book newspaper.

Cartoons would seem to lack this possibility—everything is drawn out on the page, never simply photographed. One thinks instead of the heroic animated journalism of Winsor McCay and his imagined account of “The Sinking of the Lusitania” of 1918—a frenzied, conscientious recreation of the present down to its every rivet. A flip-book newspaper.

But there are unconscious cartoons, too, and Friz Freleng’s “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” is this sort of rare achievement. We can cite several interlocking reasons that this Merrie Melody exists: to harmlessly fill out a theater program, to promote sales of related “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” merchandise (sheet music, 78 rpm records, etc.), to meet contractual booking obligations between distributors and exhibitors. Pristinely documenting the movie-going experience of 1937 was the least of these motivations.

At first, this sounds somewhat silly. The theater patrons of “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” are dogs and ducks and hippos and pigs and goats. Some realism there.

And yet there’s so much to learn about the experience of going to the movies here. From the start, there’s the listlessness of double bills—a Depression-minded value innovation that was already regarded as exhausting in 1937. (Surprising to learn today, but double features were routinely condemned by the same community groups concerned with film content. Around this time, Chicago’s Parent-Teacher Association even sponsored a citywide anti-double bill ordinance.)

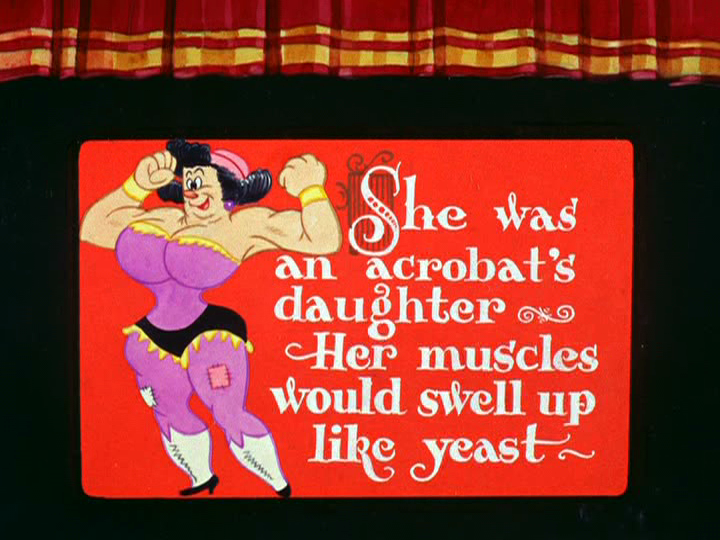

Every detail is just accidentally right. The way the traveler curtain opens immediately after the first frame hits the screen—a classy touch that today’s curtain-less multiplexes can’t touch. The ever-present popcorn pitch. (Say, is this just one big concession stand that happens to also show movies?) The awful sightlines—made even worse when that fat bozo in front of you waddles his way to the aisle. The loudmouth kid who ruins the whole movie. The free-wheeling and untidy movement between on-screen subjects and live performances. The song slides that audiences lap up. (How’s this for attention to detail? Two of the slides are broken, with prominent cracks indifferently thrown up on screen. No exhibitor worth his salt would bother replacing these slides—or check to make sure that a spittoon announcement didn’t find its way into a song sequence.)

Nothing is exaggerated enough to qualify as satire, per se.

Nothing is exaggerated enough to qualify as satire, per se.

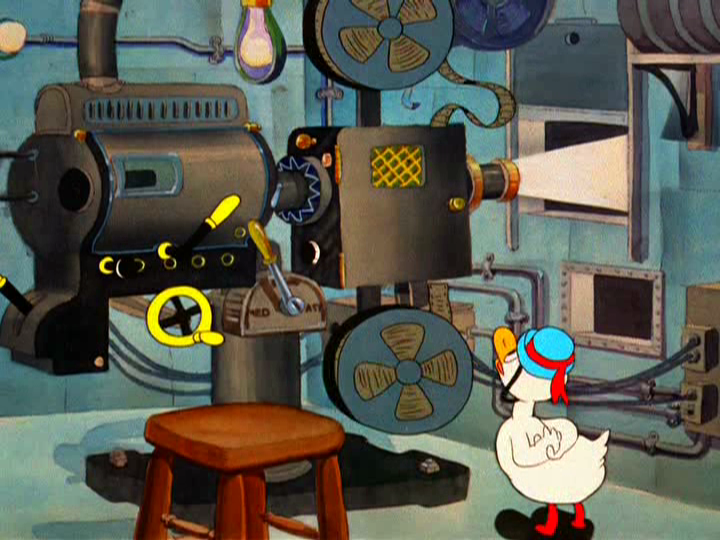

Even when “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” tries to be totally fabulist, Freleng and his writers can’t help but inject some correct observation. Late in the picture, the little duck wanders into the unattended (!) projection booth. We’ve never seen a 35mm optical sound projector that invites the projectionist to select Slow, Med., or Fast, but damned if threading the feed reel clockwise wouldn’t produce the jerky pulldown shown here.

And this is to say nothing of the chutzpah of Warner Bros. skewering The Petrified Forest, one of the studio’s major hits of the previous year, in the effete doggerel of Petrified Florist.

Above all, “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” emphasizes the strange sociality of movies in the thirties. There’s a whole communal component outside the movies themselves and perhaps greater than them. “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” possesses a cumulative energy, as if goading the audience to recognize its own nightly plight and chuckle about that recognition. It supposes a certain shared experience (and a fondness for it) that seems especially moving today. (Can you imagine a comparable short that kids anti-piracy notices and army recruitment trailers? Present-day accessories are simply not enjoyable.)

It didn’t matter what was playing. You were bound to get something good. (Actually, among the features, you were, more often than not, bound to get something bad, but many a newsreel and musical short could save an otherwise forgettable program.) “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” reminds us just how good it could be.

FOR FURTHER READING

Margaret Farrand Thorp’s America at the Movies (Yale University Press, 1939) is practically a book-length elaboration upon “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter.” It’s also among the two or three most profound books ever written about cinema. It’s long out of print, but you can usually find it among the usual suspects.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening “She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter” before Of Human Bondage at the Portage Theater on November 2 as part of its Classic Film Series. See our current calendar for more information. And please do not spit on the floor!