Is there any more dismissive response to a film than slagging it off as “dated?” Does a film lose its relevance merely because its clothing and hair styles are passé, its slang forgotten, its topicality turgid, its passions yoked to a particular time and place?

It’s a charge related to, but ultimately distinct from, the realization that a beloved film’s attitudes toward gender or race are indefensible. It shouldn’t be controversial to acknowledge that The Birth of a Nation (1915) advocates white supremacy, that Gone with the Wind (1939) puts a positive spin on marital rape, or that casting Mickey Rooney as a Chinese landlord in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) is an act of thermonuclear indifference. It’s legitimate to view those films as products of the culture that produced them, as failures of empathy and imagination that reflect the limitations of their social horizons.

Grasping and articulating that failure is an act of engagement; curtly writing a film off as “dated” is not.

It’s a label that’s most frequently applied to films that were treated as profound generation statements when they were new: The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) or Rebel Without a Cause (1955) or Easy Rider (1969). The very earnestness of these films—the aspiration to articulate a social vision in thoroughly contemporary terms—marks them as too rooted, too specific for viewers who come to them later. At best, the films might enjoy resurgence as emblems of retro chic. A similar fate may well befall the unapologetically ambitious, sprawling network narratives of the 1990s and 2000s such as Short Cuts (1993), Magnolia (1999), Babel (2006), or the already-dismissed-and-dismembered Crash (2005).

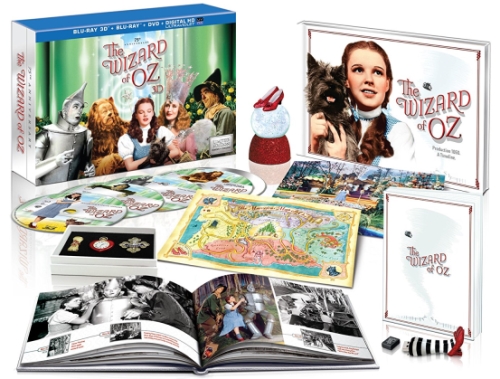

And what is the opposite of a “dated” film, exactly? The obvious answer—a “timeless” film—reveals the limitations of these terms. For what is a “timeless” film, other than one ratified by evergreen salability? The prime examples of so-called “timeless” films are those that are marketed to us over and over again—The Wizard of Oz (1939), the Disney animated classics, the Star Wars films—in periodic theatrical reissues, deluxe DVD and Blu-ray box sets, and innumerable toys, lunchboxes, apparel, etc. (Indeed, it is often the very act of suppressing the “dated” aspects—the practical effects of Star Wars [1977] replaced by CGI in the Special Editions, the racist “black Centaurette” imagery in Fantasia [1940] eliminated in subsequent releases—that renders these works “timeless.”)

And what is the opposite of a “dated” film, exactly? The obvious answer—a “timeless” film—reveals the limitations of these terms. For what is a “timeless” film, other than one ratified by evergreen salability? The prime examples of so-called “timeless” films are those that are marketed to us over and over again—The Wizard of Oz (1939), the Disney animated classics, the Star Wars films—in periodic theatrical reissues, deluxe DVD and Blu-ray box sets, and innumerable toys, lunchboxes, apparel, etc. (Indeed, it is often the very act of suppressing the “dated” aspects—the practical effects of Star Wars [1977] replaced by CGI in the Special Editions, the racist “black Centaurette” imagery in Fantasia [1940] eliminated in subsequent releases—that renders these works “timeless.”)

The Film Society has a well-established taste for “dated” films. All other things being equal, an offbeat topical hook can often be the decisive factor that places a film onto our line-up. Over the past five years, we’ve shown films steeped in hippie-tinged country rock and the trad jazz revival, films about Wild West shows and Wild Boys of the Road, cautionary films about a weaponized thermos that could level Los Angeles and computerized defense systems that could destroy the whole world, jaundiced but not-unsympathetic critiques of quack medicine shows and tent revivals, romantic comedies revolving around radio jingles and wartime immigration quotas, and popular entertainment from the 1930s with singing hoboes and talking tenement buildings. Hell, we showed an entire feature film preposterously spun out from an AM radio hit about CB-talkin’ truckers.

There’s a thrilling sense of dislocation that arises when you realize that the film you’re watching was made to be absorbed immediately, enjoyed momentarily, and discarded thoughtlessly like a crumpled-up newspaper. You’re fifty or sixty or seventy years past the sell-by date, which means you probably shouldn’t eat it, but you might learn something regardless. What a stupendous accident when a film, fragile as it is, proves durable enough to outlive the people who made it and the sentiments that aroused them. This effect isn’t limited to narrative films either; one of our most consistently popular films is a fifteen-second snipe inveighing against the dangers of daylight savings time. Do people laugh because the “Save Standard Time” side lost so decisively, or because it’s staggering to contemplate anybody being sufficiently incensed about turning the clock back an hour to fund the production and distribution of an anti-D.S.T. P.S.A. to America’s theater owners?

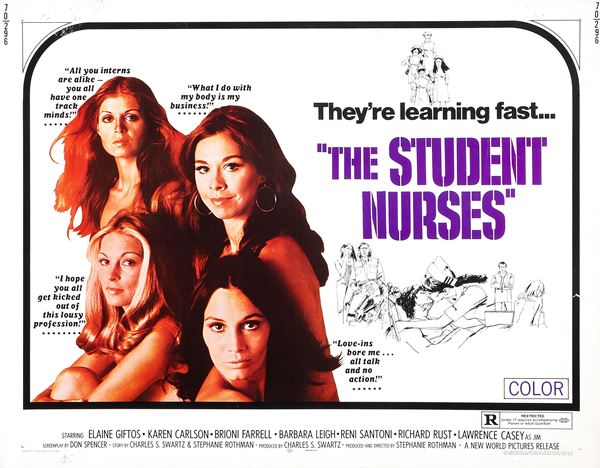

Sometimes a movie’s topicality is subtle and requires a fair bit of knowledge about contemporary tropes, anxieties, and short hand to decode successfully. Other times, the film is a screaming, all-caps, full-frontal bid for fleeting relevance. We like ’em both! No one would describe Stephanie Rothman’s The Student Nurses (1970) as a subtle movie, but this sexed-up exploitation show addresses a woman’s right to an abortion (and, for that matter, the burgeoning artistic and political consciousness of the Chicano movement) much more directly than any of the sober, responsible big studio productions of its era.

Another NWCFS favorite, Zardoz (1974), is so bizarre that it can only be assigned to the distant, incomprehensible past—and yet it’s generally underrated as a sincere reflection of its addled, terrifying moment. With Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb flying off store shelves and unprecedented resource shortages forcing drivers to queue up for gasoline, Zardoz portrays immortality and abundance as illusory, the product of a class war waged by a giant stone head and a cabal of liberated, post-heterosexual womyn. It’s not coherent enough to rate as a volley from the Left or the Right, but it cannily dismantles the utopias dreamed in 1968 as just another kind of oppression.

Another NWCFS favorite, Zardoz (1974), is so bizarre that it can only be assigned to the distant, incomprehensible past—and yet it’s generally underrated as a sincere reflection of its addled, terrifying moment. With Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb flying off store shelves and unprecedented resource shortages forcing drivers to queue up for gasoline, Zardoz portrays immortality and abundance as illusory, the product of a class war waged by a giant stone head and a cabal of liberated, post-heterosexual womyn. It’s not coherent enough to rate as a volley from the Left or the Right, but it cannily dismantles the utopias dreamed in 1968 as just another kind of oppression.

Appreciating a dated film often requires a sensibility that film reviewers are trained to reject. Are the performances good? Is the story logical? Is the craft competent? A film can fail—sometimes decisively fail—these tests and still leave us uniquely informed. There is, after all, a world outside the film—and that world matters more.

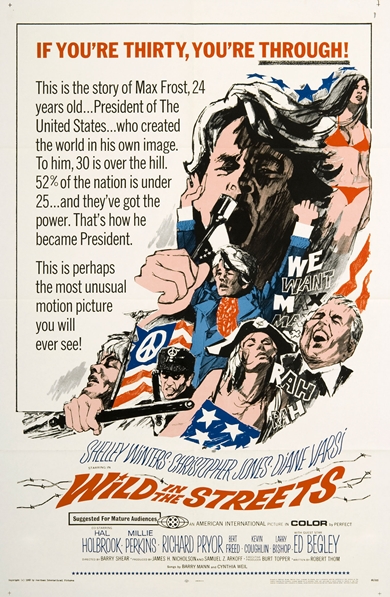

A good topical film reflects the zeitgeist in its own terms, with all the crudity, genuflection, question-begging, and ambiguity intact. AIP quickies like Wild in the Streets (1968) and Gas (1970) never would have garnered the endorsement of Students for a Democratic Society, but their satiric fury is a fair representation of the clichés, fantasies, and sentimentalities projected onto the youth movement by America at large. When we screened An American Romance (1944), my colleague Julian described this epic immigrant’s saga as a “hyper-enthusiastic, pro-American film [that] may as well have been an industrial film to boost morale at General Motors.” He meant that as a compliment: the film is the truest version of itself.

The value of topical films has been articulated most fully by the late Raymond Durgnat as an aside in his essay “Auteurs and Dream Factories”:

[Howard Hawks’] early films have ‘aged’ very well—or, more accurately, perhaps, they suit current taste. Wellman’s Public Enemy, with its serious appeal to primitive sociology, with its complex counterpoints of sympathy and contempt towards its central figure, now ‘creaks’ in the context of our changed ideas and assumptions, whereas Scarface, with its complete lack of interest in anything except revealing that Scarface is not only a rat but a coward too, who cannot but destroy all his friends and then himself, is extremely naïve . . . .

My own reaction is to find the other films more interesting than Hawks’, just because they have dated, and so say, to me, something new; whereas Hawks’ merely say, with a special deftness, what innumerable American films are interminably, and boringly, saying.

The Durgnat framework is still productive. The presidential campaign of Donald Trump has reignited interest in a cluster of films that contemplate American society’s fitness in facing down a demagogue: All the King’s Men (1949), A Face in the Crowd (1957), Bob Roberts (1992), and Idiocracy (2006), among others. They’re works of art—and undisguised social criticism. For better and worse, these films flatter their audience: your neighbor might fall for this act, but you’re too smart for that, you recognize the threat. They speak to the feelings many people experience today—the equivalent of the article about a “misinformed” voter that you share on social media, amidst approving comments from your like-minded friends. The dog whistle has changed, but the tune remains the same. Recognizing that continuity is genuinely important.

But there’s another cycle of demagogic cinema, represented by titles like The Star Witness (1931), Gabriel Over the White House (1932), Okay, America! (1932), and This Day and Age (1933). These films are “dated” in a precise fashion: they come from a brief moment when the shape of American society was actively contested and there was a substantial constituency that hoped for an American “strong man” along the lines of Benito Mussolini or Adolf Hitler—and a sizable bloc that regarded F.D.R. in precisely those terms. These films address civil liberties and the perils of mob rule, but they don’t always come to the conclusions that we want to hear from the vantage of 2016. For that reason, they remain highly educational and disarming. If you want to understand the appeal of demagoguery, you would do well to look at films in thrall to it, rather than focusing only on those that proudly know better.