Often the answer is obvious enough (housewives, teenage boys, the Friday night drive-in bumpkin, the half-conscious grindhouse denizen, etc.), but in some special cases, the interrogation itself opens up and deepens the mystery of the film in question. In those instances, the absence of a readily identifiable target audience makes the fact of a film’s production and release all the more beguiling.

Let’s talk about Wild Boys of the Road. It’s commonly reckoned an exemplar of the social problem film as developed by Warner Bros. in the 1930s. As Nick Roddick points out in his study of the studio corpus, A New Deal in Entertainment, such films were memorable and distinctive, but hardly plentiful. Warner Bros., like every other major studio, released a film a week in the 1930s, most of them bread-and-butter pictures that kidded campus life or military hijinks. The ambitious, socially-conscious pictures like Black Legion or They Won’t Forget were the exception to the surly, comfortable rule.

On a film-for-film basis, the distinction between the Warners output and that of every other studio seems to shrivel. Jack Warner made no effort to keep his politics off the backlot and modern audiences are still somewhat surprised by the forthrightly partisan gestures that crop up in the studio’s films, like the FDR portrait in Footlight Parade or the ubiquitous National Recovery Act eagle in judge’s chambers in Wild Boys. But Fox’s contemporaneous The Man Who Dared showed no compunction about the stridently Democratic remarks made by politico Preston Foster, a transparent stand-in for the recently assassinated Anton Cermak. Warner’s famous I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang is strong stuff, but so is RKO’s less-heralded chain gang picture Hell’s Highway. Urban poverty permeates the Warner Bros. pictures, but it’s equally strong in Columbia’s Man’s Castle or UA’s Hallelujah, I’m a Bum.

The whole notion of a studio-specific attitude towards daily life is a convenient critical device, but one that sometimes runs at compelling cross-purposes with the way the studio itself tried to position its films. In the case of Wild Boys of the Road, it was one of a handful of titles triumphantly announced by Warner Bros. in June 1933. (Depression or no Depression, the 1933-1934 season would see the largest capital commitment on Warner’s part in the past eight years.) The centerpiece of that announcement was, of course, the immediate production of Footlight Parade, the natural follow-up to the mega-hits 42nd Street and Gold Diggers of 1933. Without any marquee names, Wild Boys took a back seat to numerous star vehicles—including some that never reached the screen, like the Napoleon biopic that Edward G. Robinson was supposedly set to make right after completing Red Meat (itself re-titled, much less evocatively, as I Loved a Woman before release.)

The whole notion of a studio-specific attitude towards daily life is a convenient critical device, but one that sometimes runs at compelling cross-purposes with the way the studio itself tried to position its films. In the case of Wild Boys of the Road, it was one of a handful of titles triumphantly announced by Warner Bros. in June 1933. (Depression or no Depression, the 1933-1934 season would see the largest capital commitment on Warner’s part in the past eight years.) The centerpiece of that announcement was, of course, the immediate production of Footlight Parade, the natural follow-up to the mega-hits 42nd Street and Gold Diggers of 1933. Without any marquee names, Wild Boys took a back seat to numerous star vehicles—including some that never reached the screen, like the Napoleon biopic that Edward G. Robinson was supposedly set to make right after completing Red Meat (itself re-titled, much less evocatively, as I Loved a Woman before release.)

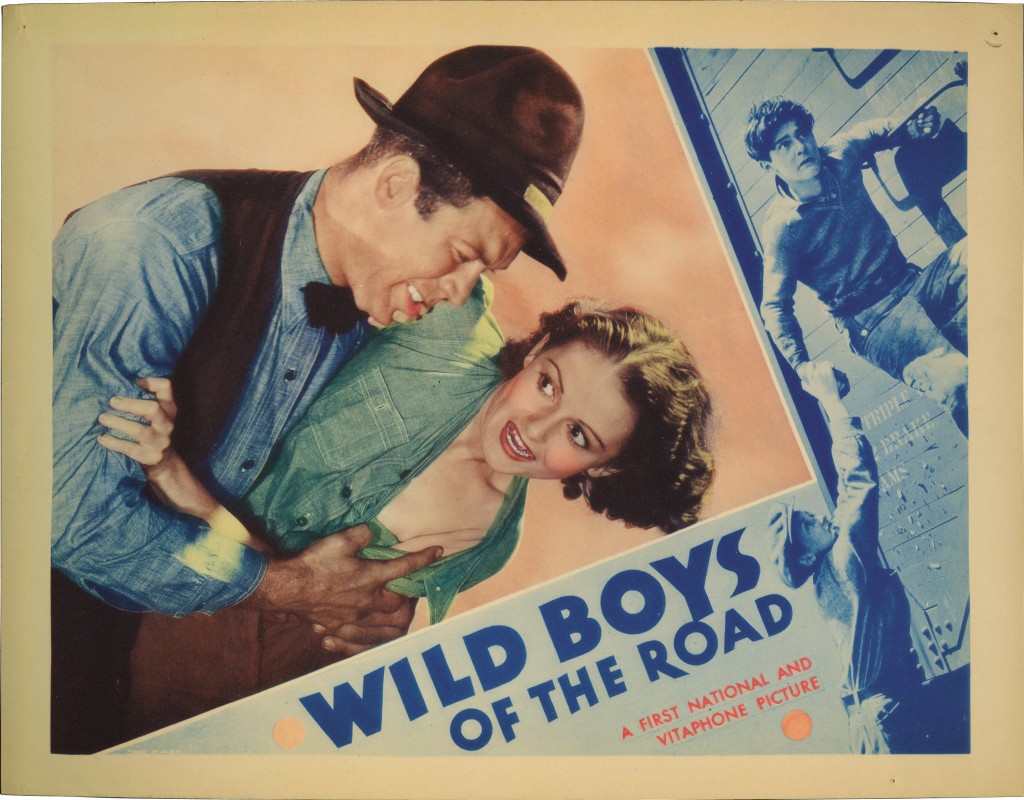

The adults in Wild Boys of the Road were below-the-line character actors in decidedly supporting roles. (Ward Bond, recognizable today but totally unknown in 1933, played the bit part of the freight train rapist.) The juvenile leads were hardly the stuff to hang a publicity campaign on. To get some idea of just how far afield Wild Boys was from a conventional business proposition for Warner Bros., consider the studio’s big pre-release gambit in the New York Sun:

Dorothy Coonan has many freckles—182 in fact. Now in her teens, Dorothy earns her living by facing the cameras and exposing her good-looking but freckled countenance to the public gaze on movie screens. [Coonan had appeared uncredited as a chorine in several Busby Berkeley musicals for Warners.] Her contract provides that she’s out of a job if she loses her freckles. So yesterday she applied for $100,000 worth of freckle insurance.

If only those kids in Wild Boys of the Road had freckle insurance; no riding the rails for them. (Coonan never had to cash in her insurance claim; she married director William A. Wellman in 1934.)

Was Wild Boys a daring social problem picture with a touch of uplift, as we tend to regard it today, or an awkward exploitation challenge with no ready roadmap? It certainly wasn’t promoted to the public as a righteous act of corporate protest. Warner’s trailer promises something like the vaguely educational cinema-smut hawked not in conventional theaters but in ad hoc fairground tents:

the LIVING TRUTH about

600,000 WILD BOYS

… INNOCENT GIRLS

Driven to

VAGRANCY!

CRIME!

FATES worse than DEATH!JOLTING FACTS about humanity’s SHAME

THE ABANDONED GENERATION!

A Thousand Times More Sensational Than

“I AM A FUGITIVE”SHOCKING ENOUGH

to make the very earth TREMBLE IN TERROR

By all accounts, when the Wild Boys were released into the wild, box office returns proved disappointing. (It didn’t help that Wellman ran $29,000 over-budget for a lean, 68-minute movie destined for double bills.) Exhibitors can be forgiven for lax support in light of Variety’s extraordinary notice:

Granting that boys on the road is a vital public question and that this picture gives it absorbing treatment, the outstanding fact is that it makes a depressing evening in the theatre, one that the general fan public would gladly avoid. Fact is that while the picture has been very well done, it should never have been done at all for general commercial release. Subjects of this class as a business proposition are a good deal like a man who ran a restaurant and insisted upon putting on his bill of fare only those items that he felt sure were good for his customers—spinach for instance—and ignored the desires of his customers for viands that might not be so good for them in general, but which they liked and wanted to buy. You might applaud his good intentions, but you’d have a poor opinion of his business capacity.

Indeed the very merits of ‘Wild Boys of the Road’ are its difficulties. The acting is so gripping and the incidents so graphic that they conspire to make the hour’s running of the subject one of considerable discomfort to the spectator. The picture presents a distressing condition only too absorbingly ….

It may be a public service to herald these facts to unwilling ears, but the theater cannot well hope to prosper materially in such a venture …. The times, in short, have anxieties enough without going to the theatre to learn about more.

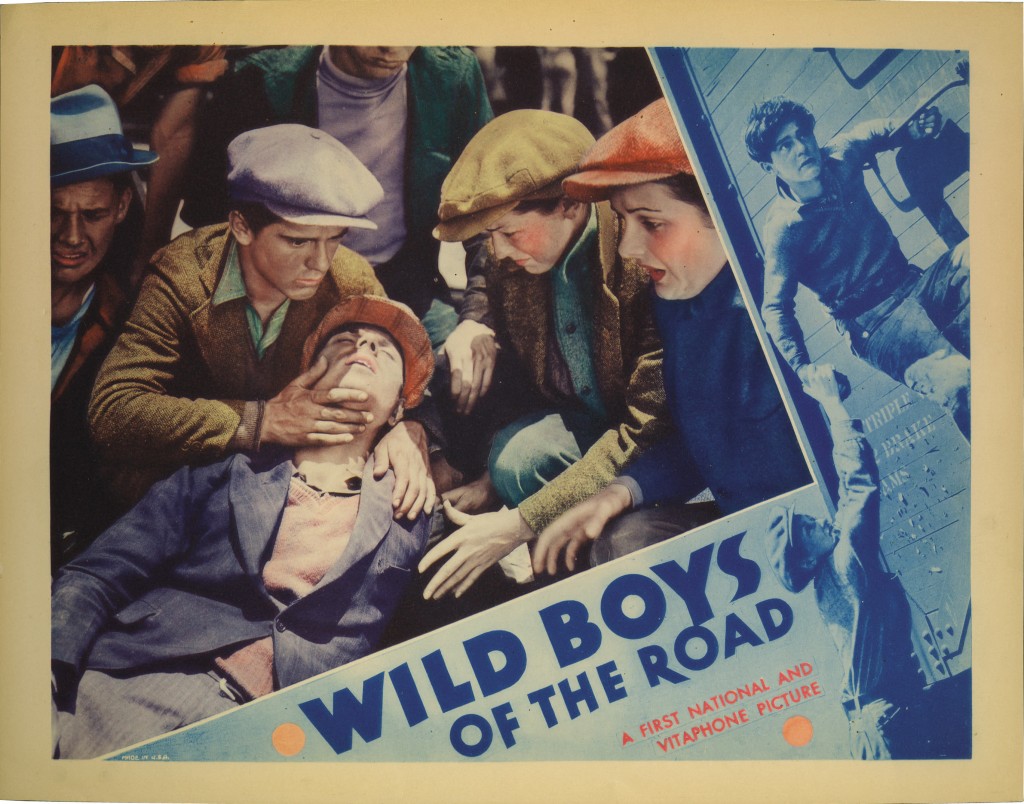

Perhaps the bottom line-oriented Variety misjudged the effect of the admittedly downbeat subject. The Motion Picture Herald advised exhibitors that the air of familiar unease could be a net-positive at the box office, with possible community tie-ins. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Times reported that Warner Bros. sponsored a preview of the film for a hundred boys from the local forestry camp, who offered a different verdict: “The boys considered the event a great lark and undoubtedly a source of satisfaction to view themselves portrayed as besting both railroad and city police in pitched battles in their travels over the land. Judge Sam Blake of the juvenile court said the picture revealed stories he hears every day in court.”

(Boys will be boys: the Wild Boys extras were paid three dollars a day to throw eggs at the police, decidedly better than standing in a breadline.)

No one would deny that Wild Boys of the Road is a confused venture on many levels. The social challenge of Wild Boys of the Road has received skeptical treatment from subsequent critics, who are quick to note that the original, harsher ending was softened and re-filmed at the behest of the studio. Yet the optimism of the finale hardly negates what’s preceded it: the half-serious notion of the kids setting up a squatter’s republic, the basically untroubled endorsement of violent resistance to police brutality, the barely-expressed but deeply felt account of fluid adolescent sexuality. (It’s a testament to artless efficiency of Wild Boys of the Road that its implied ménage-a-trois is much more affecting than the explicit arrangement of Lubitsch’s Design for Living from the same year.) These facts are more than enough to confirm Wild Boys’ radical credentials. (And besides, the re-tooled ending provides the set-up for one defiantly exuberant gesture and a related moment of recognition that’s as devastating as anything else in the film.)

No one would deny that Wild Boys of the Road is a confused venture on many levels. The social challenge of Wild Boys of the Road has received skeptical treatment from subsequent critics, who are quick to note that the original, harsher ending was softened and re-filmed at the behest of the studio. Yet the optimism of the finale hardly negates what’s preceded it: the half-serious notion of the kids setting up a squatter’s republic, the basically untroubled endorsement of violent resistance to police brutality, the barely-expressed but deeply felt account of fluid adolescent sexuality. (It’s a testament to artless efficiency of Wild Boys of the Road that its implied ménage-a-trois is much more affecting than the explicit arrangement of Lubitsch’s Design for Living from the same year.) These facts are more than enough to confirm Wild Boys’ radical credentials. (And besides, the re-tooled ending provides the set-up for one defiantly exuberant gesture and a related moment of recognition that’s as devastating as anything else in the film.)

A follow-up article in the Times offered an equally upbeat account of the city’s migrant youth dilemma, going so far as to conclude that “from them Los Angeles might gain the leaders for the next crop of useful citizens.” It’s this attitude that makes Wild Boys of the Road a quintessential picture of New Deal ideology—for once in American life, the system was blamed and the victim lionized, rather than vice versa. In today’s austerity atmosphere, where centrist wisdom supports entitlement cuts and bolsters the status quo on foreclosure, taxation, and all manner of other destructive policy choices, Wild Boys of the Road remains a rare achievement in empathy.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Wild Boys of the Road in a 35mm preservation print from the Library of Congress on May 2 at the Portage Theater as part of our Classic Film Series. Please see our current calendar for more information. Special thanks to Rob Stone and Lynanne Schweighofer. Wild Boys of the Road is the inaugural screening in our collaborative series with portoluz. Please visit portoluz to learn more about their WPA 2.0: A Brand New Day programming.