If a major American studio falls in the forest, does it make a sound?

If a major American studio falls in the forest, does it make a sound?

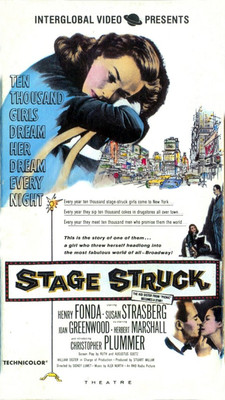

To the average movie fan in 1956, probably not. For those who got their Hollywood news from Hedda Hopper’s syndicated newspaper column, RKO’s Stage Struck sounded like business as usual, with casting news and production leaks coming at regular intervals. Early chatter had pegged Jean Simmons for the starring role of ingénue actress Eva Lovelace, but Bill Dozier, Joan Fontaine’s ex-husband and producer of high-class fare like Letter from Unknown Woman, now held the reins at the newly restructured RKO and had his sights set on Susan Strasberg. The 18-year-old actress, daughter of legendary acting instructor and Method prophet Lee Strasberg, had already acquitted herself with supporting parts in Picnic and The Cobweb, but her profile had been raised immeasurably by the Broadway success of The Diary of Anne Frank, then in the midst of a run that would exceed 700 performances. Strasberg was signed. Cameras would roll in January 1957 in New York City.

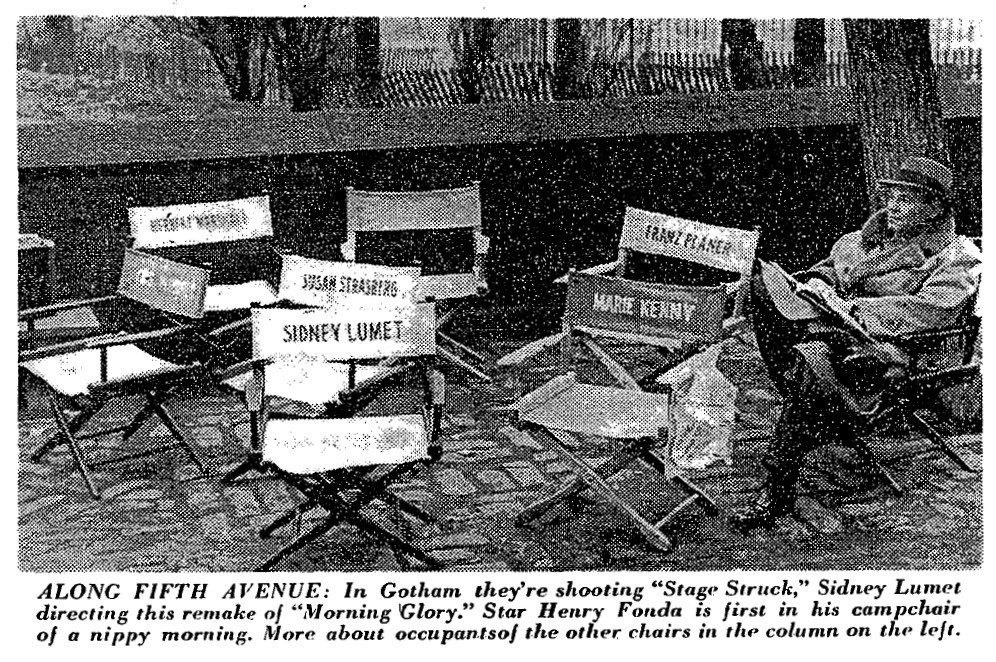

Henry Fonda’s participation was announced in August 1956. That same month, Sidney Lumet was attached as director. This spoke to enormous confidence in the theater- and television-trained Lumet, whose feature debut 12 Angry Men had already been shot but would not be released by United Artists until the following spring. Herbert Marshall was added to the rolls in September and Christopher Plummer in December.

After the shoot began the following month, Walter Winchell fanned whispers that Strasberg had been romancing James MacArthur, her co-star in the upcoming Underdog. (The son of Helen Hayes, MacArthur suggested a parallel, irresistible case of theatrical royalty.) Another syndicated columnist, Leonard Lyons, noted that the Stage Struck crew had briefly rendezvoused with the FBI when the feds paid a visit to photograph the Commies assembling at the Chateau Garden next door. The Washington Post reported on Mrs. Lee Strasberg watching her daughter with “hawklike intentness” every day on the set. “Isn’t she amazing?,” the stage mother asked. “How her grandfather would have adored her. She just IS theater, isn’t she?” Talk about Method.

All conventional stuff.

More informed industry observers saw a very different picture. Stage Struck went into production amidst the ugly and protracted unwinding of RKO, the final blow for a studio that had been mired in one crisis or another almost consistently since its founding a generation before. By the time Stage Struck finally limped to theaters in 1958, RKO itself was gone.

Stage Struck was announced as a remake of Morning Glory, an RKO hit from nearly a quarter-century ago. As Morning Glory and the Zoe Atkins play from which it was adapted were conceived fairly narrowly as vehicles for Katharine Hepburn, tailored carefully to evoke the actress’s own familiar New England-to-Broadway ascent, this was not a natural property for a Technicolor facelift.

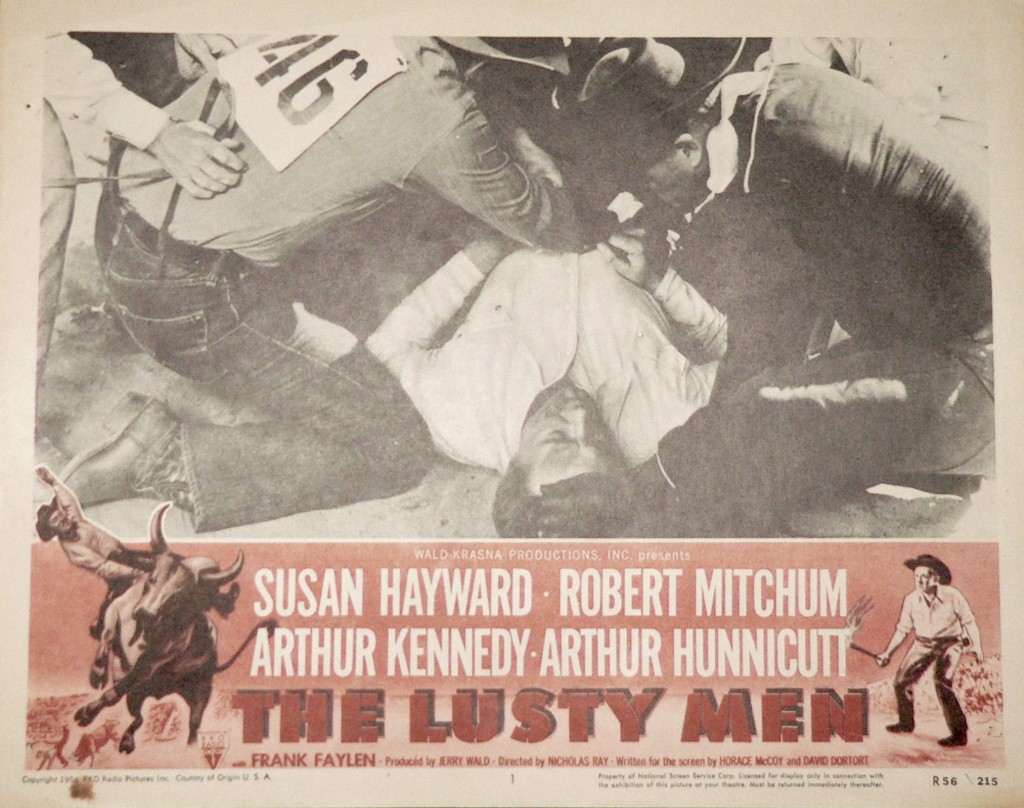

The recent success of Warner’s remake of A Star is Born surely helped, but probably not as much as the fact that cash-strapped RKO would have found any pre-existing script appealing in 1956. After a disastrous seven years under the lackadaisical management of Howard Hughes, the studio had recently been sold to the General Tire & Rubber Company. Inheriting a barely functioning studio with massive debt, General initiated a fire sale of corporate assets throughout 1955-’56. Hughes’s regular production shutdowns, cash flow problems, and endless tinkering had left a puny theatrical slate, which the new RKO complemented with an uncommonly high number of reissues—re-releasing not only proven box office hits like King Kong and I Walked with a Zombie but also a half-remembered succès d’estime like Citizen Kane. It’s a measure of RKO’s desperation that they pushed The Lusty Men, scarcely four years old and no exhibitor’s idea of hotly-demanded return engagement, as a reissue attraction.

But theatrical oldies were, at best, a side story for RKO in 1956, which had recently made a decisive step towards disseminating its library assets through TV. General Tire’s television subsidiary, General Teleradio, had already demonstrated tremendous success with its Million Dollar Movie slot on New York’s WOR, which in its earliest incarnation ran the same movie sixteen times (!) over the course of a single week. But quality product was hard to come by, with the major studios extremely reluctant to license their back catalogue to TV. British fare and low-budget independents were the rule, with studios sitting on the sideline. (Remarkably, the studios’ collective reticence to lease their libraries to television at rock-bottom prices was pursued—unsuccessfully—as an anti-trust action by the Justice Department; remember that studios, following the Supreme Court’s 1948 Paramount ruling, were under intense scrutiny on all matters with any appearance of collusion.)

But theatrical oldies were, at best, a side story for RKO in 1956, which had recently made a decisive step towards disseminating its library assets through TV. General Tire’s television subsidiary, General Teleradio, had already demonstrated tremendous success with its Million Dollar Movie slot on New York’s WOR, which in its earliest incarnation ran the same movie sixteen times (!) over the course of a single week. But quality product was hard to come by, with the major studios extremely reluctant to license their back catalogue to TV. British fare and low-budget independents were the rule, with studios sitting on the sideline. (Remarkably, the studios’ collective reticence to lease their libraries to television at rock-bottom prices was pursued—unsuccessfully—as an anti-trust action by the Justice Department; remember that studios, following the Supreme Court’s 1948 Paramount ruling, were under intense scrutiny on all matters with any appearance of collusion.)

General Teleradio—now merged with RKO into a new entity called RKO Teleradio—saw the immediate potential to unload its assets. Selling the entire 741-feature library outright to cola manufacturer C&C, which in turn licensed the films in perpetuity to stations across the country, RKO had gone whole hog for television.

In 1956, RKO Teleradio circulated a glossy catalogue of its library offerings, RKO’s Finest Fifty-Two, which promised a year’s worth of quality television programming. (Even civil servants with long-standing concerns about the vertically-integrated film industry could never have anticipated this new market efficiency: the hard-cover RKO’s Finest Fifty-Two was bound in Bolta flex, a product of General Tire & Rubber Co.) For a studio with its back against multiple walls, the RKO Teleradio catalogue struck a notably triumphalist tone in describing recent broadcast history:

Network television itself began to change. The hour-and-a-half “spectacular” or one-shot came into being. But the formidable production costs and difficulties of such shows ruled out the possibility of sponsorship on any regular basis. And there was no guarantee that anyone could come up with a hit every time he took a gamble on one of these shows.

What might happen then, some advertisers began to wonder, if a sponsor or group of sponsors could provide a weekly program of feature films of network caliber—finished, polished to Hollywood’s highest gloss, and already proved in the decisive arithmetic of box-office success?

The answer was, nobody could. The major Hollywood studio vaults remained locked to television.

And then General Teleradio unlocked them. And overnight the whole film-on-television picture changed.

According to RKO, its antique wares represented hundreds of millions of dollars in mature investment, each film filled with star power that TV producers could never afford to attain. RKO features had already been audience-tested and audience-approved. (“Movies are better than ever—on television,” said RKO, cheekily tweaking an industry slogan launched to get the audience back in the theater. Did they even care anymore?) Further, RKO features reminded sophisticated viewers of production values they’d come to miss on TV programs, for “Hollywood budgets of time and money permit actual background and locations.” “Never a fluffed line or the sight of a mike boom or stage hand to break the illusion,” RKO chortled.

In truth, RKO was caught up in its own corporate illusions. Despite cracks about unprofessional product, RKO would need to emulate TV methods if it hoped to maintain any standing as a studio. Industry veterans took notice when television vets Morton Fine and David Friedkin adapted tube practices to deliver the 86-minute Capital Offense (re-titled Hot Summer Night for release) to typically bloated M-G-M in a mere nine days. Meanwhile RKO contracted to release The Violators, an independent production shot at New York’s Production Center Inc., a flexible three-sound-stage facility that leased space to television crews between film shoots.

In truth, RKO was caught up in its own corporate illusions. Despite cracks about unprofessional product, RKO would need to emulate TV methods if it hoped to maintain any standing as a studio. Industry veterans took notice when television vets Morton Fine and David Friedkin adapted tube practices to deliver the 86-minute Capital Offense (re-titled Hot Summer Night for release) to typically bloated M-G-M in a mere nine days. Meanwhile RKO contracted to release The Violators, an independent production shot at New York’s Production Center Inc., a flexible three-sound-stage facility that leased space to television crews between film shoots.

Just before Christmas, 1956, RKO President Daniel O’Shea denied rumors that the company planned to shutter its Hollywood studio, while allowing that RKO was indeed shuffling some personnel to a Culver City office and had already discharged many of its 2,000 staff. (The Culver City office, still known as the old Pathé lot, would soon be rented out as a studio-for-hire, allegedly at a profit.) All four productions planned for early 1957 (including Stage Struck) would be shot on location and the studio itself had thus become superfluous. RKO promised an investment of $10 million for this quartet. Disarray was rampant, with new details trickling out in trade rags like Boxoffice. One big production, Bangkok, was postponed when topline talent proved unwilling or unable to travel to Thailand during the optimal seasonal timeframe of December-January. Around the same time, the studio quietly announced it had sold two pieces of Washington, DC real estate (including its flagship Keith Theatre) for $1.5 million.

As planned, Stage Struck began filming on 14 January 1957. The next week, RKO announced the dissolution of its domestic distribution infrastructure, which resulted in some 800 pink slips at 32 exchange offices throughout the country. Universal-International would handle ongoing theatrical requests on the studio’s 1953-’56 product, slashing mounting red ink for RKO. The studio’s publicity staff was cut to two people. All appearances to the contrary, RKO maintained it was still a going concern. After all, it was making Stage Struck, wasn’t it?

Incidentally, Universal had not contracted to distribute Stage Struck or any of the studio’s other unreleased films. To hear RKO tell it, this move demonstrated the beleaguered studio’s good faith intent to resume full operation after eliminating assorted liabilities. But it begs the question: could Universal even bank on the RKO team finishing Stage Struck?

If Stage Struck was the last gasp of a dying studio, the talent betrayed no sympathy for the style and principles that RKO represented. Shooting in the midst of a Gotham blizzard with ace cameraman Franz Planer, 27-year-old producer Stuart Millar relished the location difficulties. “We don’t want any Hollywood sunlight in this one,” he told the New York Times.

Lumet’s bluster went further in shunting traditional glamour:

The movie audience has been shown over and over again what war was like on D-Day. But do they know the tension, the color, the anticipation and the excitement backstage on opening night? Susie’s nervous. The audience is waiting. Lights are ready, curtains, all the technicians are in touch over the squawk boxes. Then the curtain goes up. When Susie makes her entrance, there’ll be an absolute hush. I want to show what it’s really like. No hoke, no propping, no music with violins backing it. The real thing.

Lumet may as well have been describing the behind-the-scenes anxieties plaguing Stage Struck. By May 1957, while Stage Struck was reportedly in the final stages of post-production (scoring and editing), RKO announced Millar’s voluntary departure from the studio. It was only the second picture of the young producer.

Would Stage Struck be released? The film had most definitely been previewed for industry types by August 1957: Hedda Hopper saw it and pushed fresh-faced Christopher Plummer as M-G-M’s next Judah Ben-Hur. “To me, he outshone them all, and I do mean Susan Strasberg, Henry Fonda and Hebert Marshall — and brother, that’s outshining.”

In October, industry buzz linked Strasberg to a new project, William Dieterle’s The Texas Trail. “She is still to be seen in the unreleased Stage Struck with Henry Fonda in the pictures,” the Los Angeles Times noted dryly. On 15 March 1958, Strasberg appeared with Arthur Knight and Yael Woll in a pilot episode of The Story of Film Techniques for New York’s WRCA-TV. A clip from the forthcoming Stage Struck was to be discussed. The New York Times promised a charity premiere “late next month” to benefit the Actors Fund of America.

Stage Struck finally opened in Los Angeles on 9 April 1958. The New York charity premiere followed on 22 April. At last—a promise kept!

Stage Struck finally opened in Los Angeles on 9 April 1958. The New York charity premiere followed on 22 April. At last—a promise kept!

Only it wasn’t RKO presenting Stage Struck at the Normandie. Distribution was overseen by Buena Vista, the Disney subsidiary established in 1954 when the animation studio feared the imminent collapse of its releasing partner of the past two decades—RKO. Exhibitors in sophisticated eastern cities like Boston and New York returned above-average grosses, but the film stalled out west, with Los Angeles, Indianapolis, and Denver reporting mediocre box office.

The reputation of Stage Struck has hardly shifted since 1958. Its cast and crew rarely mentioned it in subsequent interviews and home copies remain scarce. (Does anyone even know who owns it these days? Presumably not InterGlobal Video, the outfit that released it on VHS in 1986.)

In one respect, Stage Struck was crucially and uncharacteristically lucky. Buena Vista saw fit to treat this maligned orphan to release prints in IB Technicolor. Although new 35mm prints of Stage Struck have likely not been made since 1958, original copies still retain their brilliant, garish color. (‘Baghdad-on-the-Hudson,’ the New York Times called its Greenwich Village footage.) This is more than can be said for original prints of M-G-M and 20th Century-Fox productions released with considerably more fanfare in ’58, by which time both studios had foregone the expensive Technicolor dye-transfer process. Stage Struck is more than due for a reevaluation—and thanks to private collectors, it can have one.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Stage Struck in an original 35mm IB Technicolor print on August 1 at the Portage Theater as part of its Classic Film Series. Print courtesy of the Radio Cinema Film Archive. Please see our current calendar for further information.