Last week the Los Angles Times published an unusual op-ed about young peoples’ attitudes towards movies from Neal Gabler, the writer responsible for such insightful social histories as An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood.

I call the article unusual not because its topic is especially exotic (more on that in a moment) but because it reads with such befuddled contempt for an entire generation. Withholding any constructive solution to the supposed problem, Gabler seems less interested in fostering film appreciation than in griping about kids these days. In other words, it calls to mind the class of knee-jerk sociology which Empire of Their Own or Gabler’s more recent Walt Disney biography studiously avoid. Here’s a representative paragraph:

Young people, so-called millennials, don’t seem to think of movies as art the way so many boomers did. They think of them as fashion, and like fashion, movies have to be new and cool to warrant attention. Living in a world of the here-and-now, obsessed with whatever is current, kids seem no more interested in seeing their parents’ movies than they are in wearing their parents’ clothes. Indeed, novelty may be the new narcissism. It obliterates the past in the fascination with the present.

Perhaps Gabler speaks of narcissism with more affection than I can ascertain, but the curiously moralizing proposition remains: some inner deficiency prevents kids today from grokking their parents’ favorite movies, passing them over in favor of Twitter or iPads or whatever new widget commands their attention. (This claim is especially suspicious given that Gabler opens his article with a complaint about The Amazing Spider-Man supplanting collective memory of 2002’s Raimi-Maguire Spider-Man—a less urgent or sincere crisis could not be imagined. For an article nominally about marketing imperatives distorting cultural priorities, Spider-Man is one loaded proposition.)

Perhaps Gabler speaks of narcissism with more affection than I can ascertain, but the curiously moralizing proposition remains: some inner deficiency prevents kids today from grokking their parents’ favorite movies, passing them over in favor of Twitter or iPads or whatever new widget commands their attention. (This claim is especially suspicious given that Gabler opens his article with a complaint about The Amazing Spider-Man supplanting collective memory of 2002’s Raimi-Maguire Spider-Man—a less urgent or sincere crisis could not be imagined. For an article nominally about marketing imperatives distorting cultural priorities, Spider-Man is one loaded proposition.)

Gabler goes on to pronounce the situation totally different from prior generation gaps, incredibly citing his own baby boomer compatriots as avid consumers of antique media. “[B]oomer audiences didn’t necessarily believe their aesthetics were an advance over those that had preceded them,” Gabler writes, though for every ’60s student who hung a W.C. Fields poster in her dormitory, there were doubtless many others who reflexively distrusted any old John Wayne Western in the wake of The Green Berets. Boomers had their Rolling Stones and their Zappa, but surely they too longed for the way Glenn Miller played just like Archie Bunker, no?

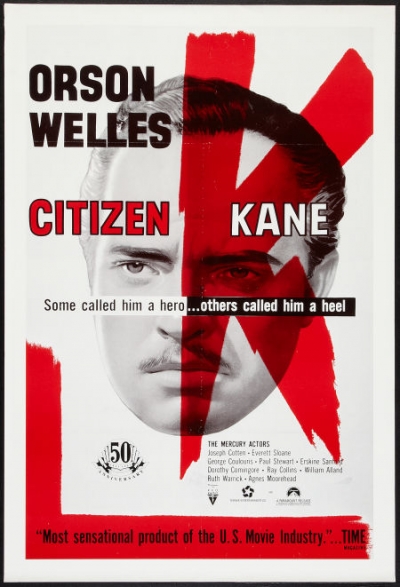

Boomers, Gabler says, followed critics like the late Andrew Sarris, who excavated the movies of the past. (This is the same decidedly non-boomer Sarris who once revised his opinion on 2001: A Space Odyssey “while under the influence of a smoked substance that I was assured by my contact was somewhat stronger and more authentic than oregano on a King Sano base.”) But these days even film students find Citizen Kane and The Godfather boring, insufficient distractions in today’s 24/7 media landscape:

What this points to is that movies may have become a kind of “MacGuffin” — an excuse for communication along with music, social updates, friends’ romantic complications and the other things young people use to stoke interaction and provide proof that they are in the loop. A film’s intrinsic value may matter less than its ability to be talked about. In any case, old movies clearly cannot serve this community-building function as they once did. More, the immediacy of social networking, a system in which one tweet supplants another every millisecond, militates against anything that is 10 minutes old, much less 10 years.

This is a paragraph that swells with strange contradictions. Movies today are, on one hand, mere adjuncts to social experience, just another Facebook update. They’re not autonomous works of art to be studied and revered on their own terms. And yet the classic movies fail to fulfill their ‘community-building function’—something they presumably achieve only by acquiescing to the whims of said community. (Perhaps even on Facebook, where over 2,400 users have linked Gablers’ article?) Somehow, people getting together and talking about movies doesn’t count as people getting together in the first place.

All movies were, of course, once new, and likewise competed for the attention of addled young people against the considerable appeal of the jukebox, the radio, the sock hop, comic books, and endless television programming—or, in another era, the Atari arcade and the disco. Having seen a movie was always just as much a bragging right as an aesthetic privilege. How else would movies foster community other than acting as disposal cultural currency? Likewise, how much consideration did previous generations give individual movies when they automatically saw two or three a week as a cheap and rewarding form of recreation? Are these experiences any less legitimate if moviegoers forgot the details ten minutes after the show ended? Ultimately, it comes down to whether you think films are degraded by being part of a broader cultural flotsam or whether they’re inextricably and productively bound up with those circumstances.

What would Gabler think about Michael King’s account of the audiences at our predecessor, the late LaSalle Bank Cinema, who resolutely refused to revere the holy celluloid:

[T]hey were just movies. More than anything, the Bank was a throwback to an even earlier time, when movie theaters were social hubs for the surrounding community. People don’t show up at the AMC River East hours before every single show to talk with friends that they made there, and then hang around talking afterwards until the last possible minute, when the programmer sends them home. This happened without fail, before and after every Bank show I ever worked, and is ultimately what I’ll miss most about the place: the feeling that the movies were incidental.

But this deeply social idea of film-going—with the community as an end, rather than the films themselves—is unfashionable these days. Perhaps as unfashionable as kids rushing out to see their parents’ movies.

But the fact of the matter is that Gabler’s grim observations are nothing especially new. Almost ten years ago, Ty Burr penned a much more respectful, if equally puzzled, piece in the Boston Globe Magazine surveying the ‘roughneck new canon’ of Pulp Fiction and Run Lola Run. (Burr also interviewed a few hot-shot auteurs for the piece, including David Fincher, who ruled that ‘Casablanca now feels like a stage play. It’s beautifully, classically made, but in terms of the language of cinema, it’s almost irrelevant.’)

But the fact of the matter is that Gabler’s grim observations are nothing especially new. Almost ten years ago, Ty Burr penned a much more respectful, if equally puzzled, piece in the Boston Globe Magazine surveying the ‘roughneck new canon’ of Pulp Fiction and Run Lola Run. (Burr also interviewed a few hot-shot auteurs for the piece, including David Fincher, who ruled that ‘Casablanca now feels like a stage play. It’s beautifully, classically made, but in terms of the language of cinema, it’s almost irrelevant.’)

As someone who is under 30 and has spent his entire professional life showing films and trying to get other people to see them, let me suggest a semantic distinction with rather far-ranging implications. I’ve never thought to describe any movie as ‘old,’ just as surely as I’ve never promoted one on that basis. Though the vintage of a film may tell us a lot about what to expect with respect to attitude, pacing, and craft, it reveals next to nothing about quality or lasting value. (There’s an endless supply of bad old movies, just as surely as there are an overwhelming number of worthwhile modern ones.)

Instinctively, of course, many people do leap to these judgments at the sight of, say, a black-and-white film on television. For what it’s worth, I’ve found that this antipathy has no significant correlation to the age of the viewer, with some of the oldest folks expressing the most vehement objections. If such a prejudice does exist, why exacerbate it by putting forward ‘old movies’ as a category of cultural patrimony? (Can the government make you buy broccoli?, Antonin Scalia recently mused, fishing for reasons to gut the Affordable Care Act. Perhaps conservative jurists would have prevailed in NFIB v. Sebelius with the equally frightening question, Can the government make you watch old movies?)

In enumerating some sample reasons that millenials may be disenchanted with old movies, Gabler pointedly broaches the possibility of the movies being “politically incorrect,” as if too-sensitive souls reject them out of misplaced offense. But taking note of an older film’s misogyny or racism or homophobia actually represents a critical engagement with the material and acknowledges the film as a legitimate artifact of evolving social mores. Would it be better to simply ignore this content and lionize the movies anyway?

In enumerating some sample reasons that millenials may be disenchanted with old movies, Gabler pointedly broaches the possibility of the movies being “politically incorrect,” as if too-sensitive souls reject them out of misplaced offense. But taking note of an older film’s misogyny or racism or homophobia actually represents a critical engagement with the material and acknowledges the film as a legitimate artifact of evolving social mores. Would it be better to simply ignore this content and lionize the movies anyway?

Simply stated, pushing ‘old movies’ misstates the reasons for being excited about them in the first place. Why should anyone watch something for the sole reason that it’s old? This is a sputtering revanchist position guaranteed to provoke backlash. (Gabler draws an analogy to literature, but never promotes the cause of ‘old books,’ much less ‘old plays’ or ‘old music.’ Does anyone?) It’s unrealistic, too, to assume that young people will flock to ‘old movies’ on the basis of the nostalgic sales pitches—the stars, the memories, the magic of the silver screen!—which they often receive these days. How can anyone feel authentic nostalgia toward things that predate one’s own life?

If young people are still going to find old movies relevant in the new century, it stands to reason that a different kind of case needs to be made on their behalf, one that’s less about received opinion and instead acknowledges these films as living, contested, strange, and sometimes dangerous things. Perhaps Citizen Kane and The Godfather are now too familiar to provoke awe and mystery, but perhaps, too, this is a good reason to promote a less static canon. (Anyone up for My Son John, Uptight, The New Centurions, Force of Evil, or One Way Passage?) Shifts in narrative structure, editing rhythm, screenwriting technique, political consciousness, and, yes, fashion, have rendered earlier run-of-the-mill productions baroque and beguiling. The entirety of silent cinema is now unfathomably radical and interactive in its unfinished, natively open-ended form. But only for those who want to be surprised.