Which version of The Devils are you going to show on Monday?

Which version of The Devils are you going to show on Monday?

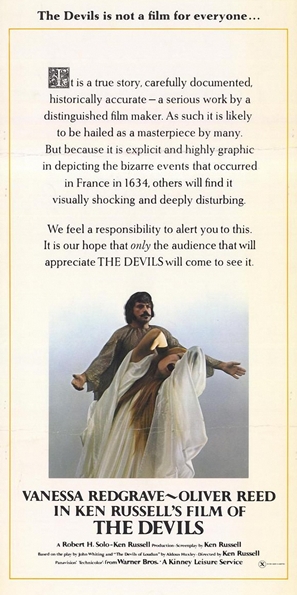

We’ve been asked this question over the phone, in person, and on social media since announcing we’d be screening The Devils at the Music Box. And it’s a perfectly reasonable question, as there are at least four versions The Devils commonly cited: the 111-minute X-rated British theatrical cut; the 108-minute X-rated American theatrical cut; the R-rated American version (either 106 or 109 minutes) released on VHS decades ago; and a spectral cut that re-integrates footage discovered by the critic Mark Kermode.

Adding to the confusion, Warner Bros. prepared a digibeta transfer of The Devils over a decade ago and commissioned several DVD extras but never released a disc—bowing, at least in the imaginations of fevered Ken Russell fans, to a Vatican conspiracy or the resurgent Evangelical stirrings of the Bush era. The studio eventually licensed the transfer and extras to the British Film Institute, which released a Region 2 DVD that runs 107 minutes—but that’s not a new iteration, just a slightly sped-up version of the 111-minute British cut because the video is encoded at the 25 fps PAL standard.

So, which one are we showing?

The fact is, film programmers frequently operate in the dark about these matters and have limited means of seeking clarification. The print arrives at the venue a week before the show (at most), and long after calendars have been printed and disseminated.

Programmers rely on distributors, archives, and private collectors to supply film prints for public exhibition. We interface with studio bookers, who almost always have no physical access to the prints they send out. At best, they have notes about the prints, but not always. The prints are usually in another building on the studio lot or located in a storage depot hundreds of miles away, operated by a third-party logistics firm in Sun Valley or Long Island City. To verify the condition of a print, let alone the specific version it represents, bookers can order an inspection from the depot (which costs money and often overstates a print’s deficiencies) or they can rely on scattered remarks from previous venues. Of course, some venues fail to report prints that have been torn in half, while others phone in a detailed assessment of every scratch and speck of dirt (and expect a price adjustment for their trouble). In an era when some studios are eager to junk prints, every condition report is a provocation and potential death sentence.