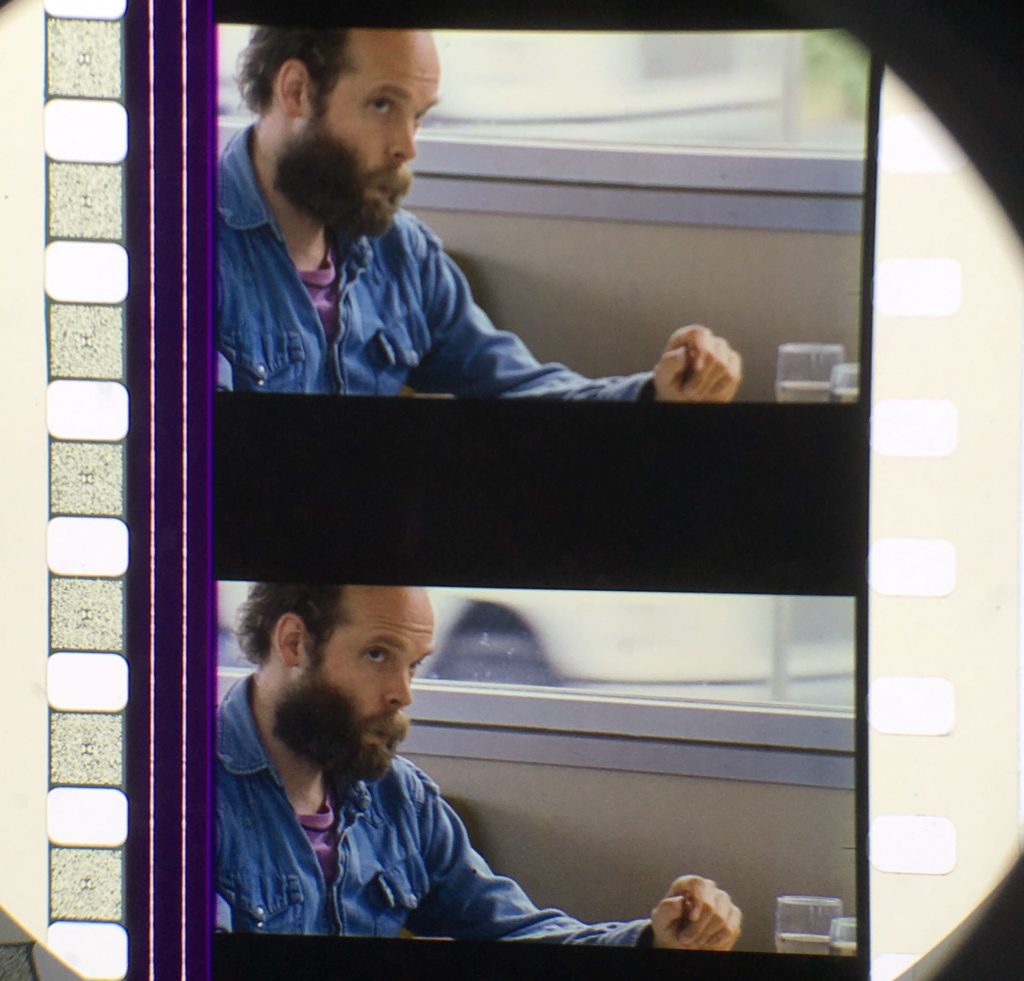

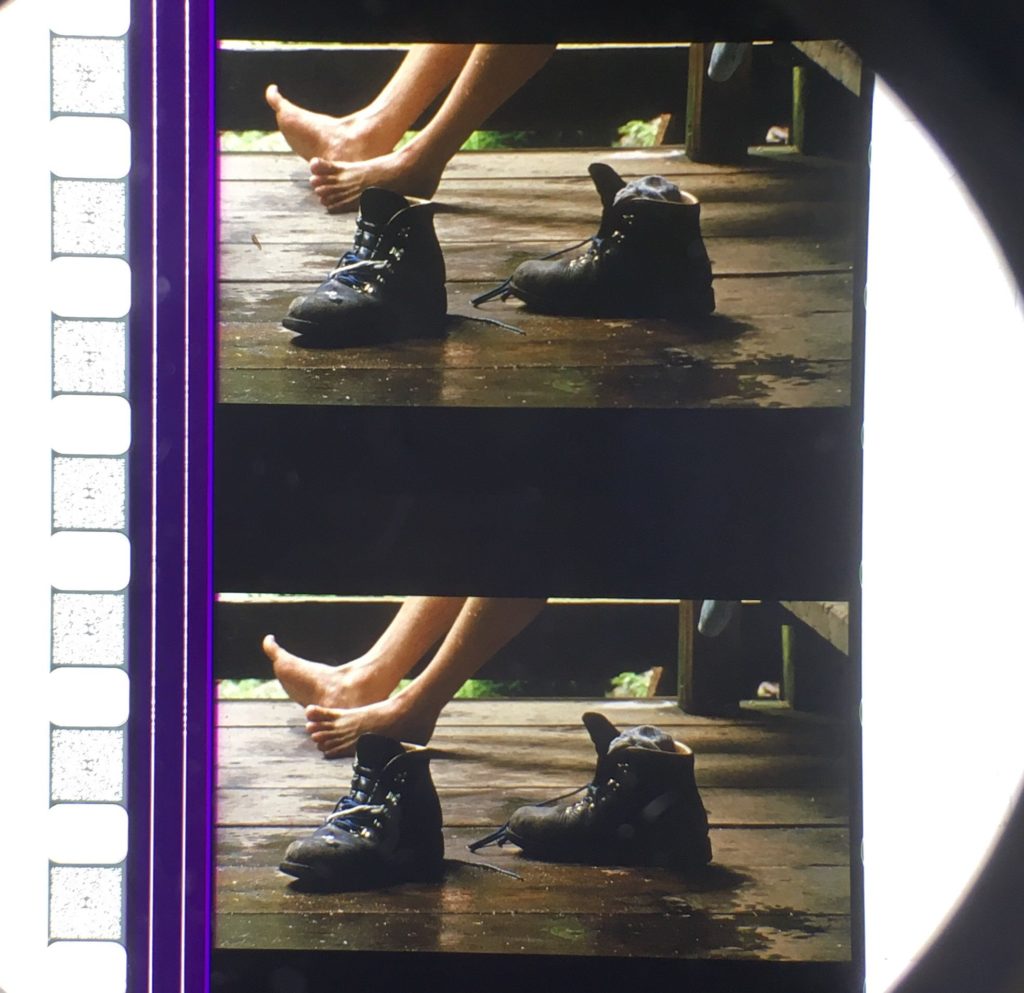

In advance of our 35mm screening of Kelly Reichardt’s OLD JOY, we exchanged a few questions over email with Will Oldham, who stars in the film alongside Daniel London. Based on a short story by Jonathan Raymond, the film follows two old friends on a road trip to a hot spring in the Oregon woods. OLD JOY was the second collaboration between Reichardt and Oldham, following the 1999 feature ODE (shot on Super 8), for which Oldham wrote the score.

Julian Antos: How did you first start working with Kelly Reichardt?

Will Oldham: If memory serves, and it may not, I met Kelly through artist Alan Licht. I have a vague recollection of having supper in Chinatown with Alan, Kelly and Todd Haynes. Some time around that point, Kelly asked if I could make some music for her ODE film. This was my first experience with scoring. Kelly sent me ODE scenes with temp music in place. I was beginning to experiment with a crude looping pedal that I’d acquired after seeing Mick Turner use one. I’d also bought an old Gibson acoustic tenor guitar. Writing and recording for ODE was a great opportunity to learn how to futz with both the looping pedal and the tenor guitar.

JA: What were some differences in the collaboration process when writing a score for a film vs. acting in a film, specifically with Kelly Reichardt but also generally?

WO: There’s no comparison between acting in a film and creating music for a score. Most importantly, I could work on the music at home. Working at home can make a big difference as far as fostering experimentation. My brother Paul recorded the music and also played bass.

JA: One of the reasons we’re showing OLD JOY is that we’re doing a series of films shot on Super 16mm. OLD JOY is particularly interesting because the camera that was used can only hold about five minutes of film per magazine, and I’m curious if that came into play at all during shooting. Did you have any sense of that time pressure?

WO: There were pressures coming from many directions in the shooting of OLD JOY. These pressures were accepted as a part of the process. Likely they helped infuse the experience with a helpful urgency. There was nobody breathing down our necks, just the tyranny of gear and a small budget.

JA: OLD JOY focuses on a relationship that has gently deteriorated, and that really comes through in a genuine and moving way. Was there much rehearsal time for this film? Had you known or worked with Daniel London before?

WO: I hadn’t known Daniel before, and our rehearsal prior to shooting was minimal at best. On ‘set’, we did have ample time to work through the scenes. The crew was very small, and actors in general can have a lot of ‘down’ time. We had no dressing rooms to retreat to, so we were pretty much always together during shooting days with nothing on our plates but the task at hand.

JA: You’ve talked before about losing interest in working as an actor because of the lack of direct communication (having to deal with agents, assistant producers, etc). Do you find that’s less the case when making records and performing music, or is it easier to avoid? Do you think it’s easier to have successful collaborations on a smaller scale?

WO: This is a bit less true now, but for most of my life the distribution of music has been far more audience-fueled than the distribution of movies has been. And making a record is cheaper than making a film, overall, which means that fewer folks are trying to steer the work. It’s always easier to have successful collaborations on a smaller scale. When I showed up for WENDY AND LUCY, a small film itself but larger in scale than OLD JOY, I felt a bit lost. I make records on what can be considered to be a very small scale. It’s the recording engineer, the other musicians, and myself. And the budgets I work with are usually tiny in comparison to those of many recording artists that you might perceive as working on a similar level to me.

JA: What did you love most about being in OLD JOY?

WO: During production, I loved the togetherness of cast and crew. I loved the accountability. When I finally saw the film screened before an audience, I began to love the experience of shooting all the more for the power and effect of the resulting film.

JA: Would you want to act in more films if there were more films like OLD JOY to act in? Are there many filmmakers working on a smaller scale today that you could imagine yourself working with? It was great to see you in A GHOST STORY!

WO: That’s a funny question. There aren’t many films like OLD JOY. My scene in A GHOST STORY was a party scene, full of ‘extras’, and yet most of the folks in the scene (and on the set) had weight; they had a story, a reason for being there, a connection to the film and the filmmakers. Unity of purpose goes a long way. Unfortunately, the world of making music and the world of making movies differ in a crucial logistical way, in that musical endeavors are often scheduled much farther in advance than film endeavors are. A movie shoot, small or large, is often finally scheduled and defined within weeks or days of the shoot; I usually book a recording session a few months in advance and live performances as much as a year in advance. This makes it very difficult to coordinate. My first love was cinema, and it was heartbreaking to grow into the knowledge that I was not built for that world, that I had got my perception of it almost completely wrong. Whenever forces align that allow me to be a fruitful part of a film, I am very happy. I think I did my favorite work in David Lowery’s short film PIONEER, and I can’t imagine the experience of that film, for me, will be topped.

OLD JOY screens on Wednesday, January 15th as part of An Expanded Celebration of Super 16, a series presented by the Chicago Film Society recognizing 50 years of the Super 16mm format. Frames pictured are from the 35mm print being screened.