Very few people have seen Michael Curtiz’s A Million Bid (1927), but it’s an interesting picture, moreso than its meager reputation would suggest. The film merits barely more than a paragraph in James Robertson’s The Casablanca Man: The Cinema of Michael Curtiz and earns a passing mention in Alan K. Rode’s newly released Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film. (Rode provides additional context on A Million Bid in his recent interview with Ben Sachs.) Yet the story of its production, release, and restoration of A Million Bid suggests a film of enduring, imponderable mysteries. Rather than attempt a critical evaluation of the film, I hope to demonstrate how rich and contradictory a record A Million Bid left behind in primary sources alone.

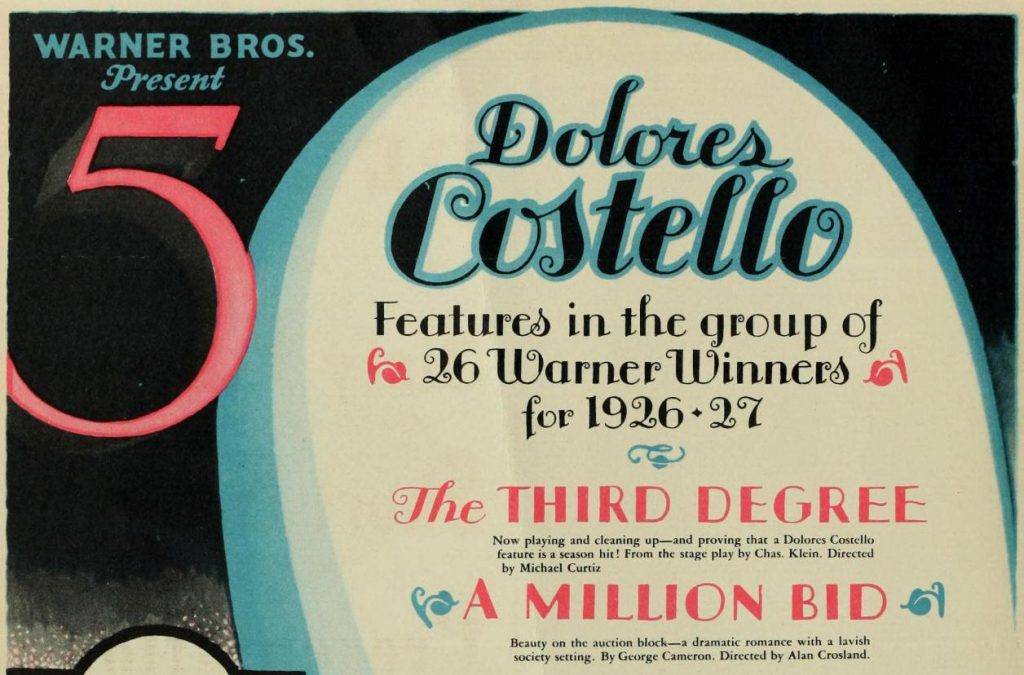

The neglect of A Million Bid is understandable. The script is rote melodrama, and the film itself (presumed lost for decades until a copy was rediscovered in Italy) is somewhat extraneous in assessing Curtiz’s legacy. It was Curtiz’s second American film, but his first, The Third Degree (1926), long ago preserved by the Library of Congress, seemed a sufficient example of his work from this period. The Third Degree was released amidst of flurry of Warner Bros. publicity, touting the studio’s newest filmmaker (already a veteran director of sixty films in Europe) as a technical wizard. “I do not see a scene with my eyes,” boasted Curtiz in a Los Angeles Times profile, “I see a scene with camera-eyes.” The film earned decent reviews, with favorable comparisons to E.A. Dupont’s Variete, one of the German imports frequently invoked as a rejoinder to pedestrian Hollywood technique.

As a studio contract director, Curtiz had only limited autonomy in choosing his own projects. Indeed, he was not initially assigned A Million Bid, which came to Warner Bros. as one distressed asset among many from the Vitagraph Company of America, a pioneering company in decline that the rising Burbank studio had recently acquired. Vitagraph had produced a film version of George Cameron’s 1908 play Agnes under the title A Million Bid in 1914, and the melodrama seemed ripe for a remake. From the start it was a Dolores Costello vehicle, but the director was replaced at least twice, and here’s where the history of this modest film becomes exceedingly confusing.

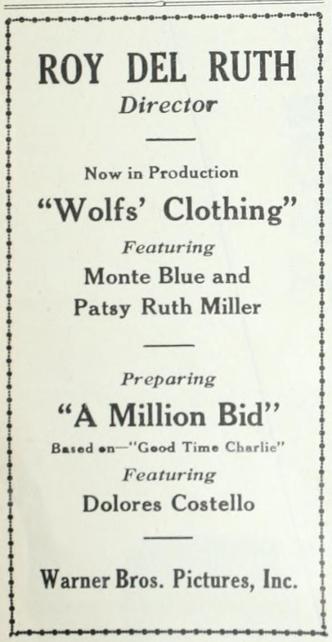

In December 1926, Roy Del Ruth took out a trade ad in Film Daily touting the fact that he was “preparing” the next Costello picture, A Million Bid, to be based on a property called “Good Time Charlie,” with no author cited. By Feb 1927, Warner Bros. was taking out a two-page trade ad in various papers previewing Costello’s productions for the 1926-1927 season, including a film called A Million Bid to be directed by Alan Crosland. This time the George Cameron source material is listed as the basis for A Million Bid. By May, the film was finished under the direction of Curtiz.

In December 1926, Roy Del Ruth took out a trade ad in Film Daily touting the fact that he was “preparing” the next Costello picture, A Million Bid, to be based on a property called “Good Time Charlie,” with no author cited. By Feb 1927, Warner Bros. was taking out a two-page trade ad in various papers previewing Costello’s productions for the 1926-1927 season, including a film called A Million Bid to be directed by Alan Crosland. This time the George Cameron source material is listed as the basis for A Million Bid. By May, the film was finished under the direction of Curtiz.

Or was it? An item in the March 26, 1927 edition of Exhibitor’s Herald passed along the rumor that “Warner Brothers have changed the title of Alan Crosland’s recently completed opus to “Old San Francisco” and the title of “A Million Bid” has been tacked onto another story, which will be made by Michael Curtiz.”

It is true that studios would sell their slate as a block, with titles announced long before the cameras rolled, which occasionally led exhibitors to charge bait and switch. The February 1927 ad describes A Million Bid as “Beauty on the auction block—a dramatic romance with a lavish society setting,” which is generic, but close enough to the finished film to suggest that the title wasn’t simply ‘tacked onto another story.’ The nod towards George Cameron’s play is another indication that Warner didn’t simply elevate Crosland’s film to Old San Francisco while fobbing off some other junk as the promised Million Bid. (Further complicating the picture, Curtiz would direct a film called Good Time Charlie later that year, its relation to the initial Del Ruth picture unknown.)

Some exhibitors bought into the conspiracy theory anyway, with the local trade group Motion Picture Theater Owners of Pennsylvania and West Virginia lodging a formal complaint with Warner Bros., charging that the studio had “deliberately taken the original picture, ‘A Million Bid,’ and retitled it ‘Old San Francisco’ and substituted an inferior picture and released it to exhibitors as the original ‘A Million Bid,’” expressing their strong “disapproval of such unethical practices.”

The Pennsylvania and West Virginia exhibitors weren’t alone in finding A Million Bid inferior. By the time A Million Bid reached the screen in May 1927, critics were pointedly more skeptical of Curtiz’s bravura technique than they had been with The Third Degree a few months prior. The New York Times review was typical:

Michael Curtiz, a Viennese director who drew attention to himself by his orgy of pictorial dissolves in his film version of “The Third Degree,” once again amuses himself by photographic stunts in his new film, “A Million Bid.” While some of Mr. Curtiz’s ideas are interesting they do not fit into this current offering as well as they did in the cinematic version of Charles Klein’s play. There are parts of this subject that are virtually lifeless and other sections that are quite bright.

Motion Picture News complained:

The theme, that of a doctor committed to his work despite any personal sacrifice involved, has been used before but there is no complaint on that score; the fault lies in the old-fashioned treatment of the story. In an attempt to add a touch of novelty a number of trick camera shots are introduced, but they mean little or nothing; some could easily be eliminated.

Michael Curtiz, the director, is a hound for camera angles and, between the weepy yarn and the angular photography, one becomes groggy.

Mr. Michael Curtiz has gone to great pains, it seems, to introduce a lot of “psychological” camera flip-flops patterned after the German nuances of “Caligari,” “Last Laugh,” “Variety,” et al. Here it doesn’t mean much. “A Million Bid” is just another movie.

Just about the only positive notice came from Moviemakers, the amateur filmmaking magazine, which was dazzled by the technical finesse and declared A Million Bid to be an instructive step forward in cinematic art:

This film shows what can be done by the use of camera tricks with a routine amnesia story, already shown on the screen some years ago. By his swift juxtaposition of shots of a moving train, of flashbacks, and of a wedding that is taking place simultaneously, Mr. Curtiz has given psychological significance and emotion power to an ordinary coincidence scene. As the train rushes through the night, by his moving shots of sections of the engine, of the rails and the ground rising to meet it as it tears through space, he has conveyed an overpowering sense of speed and power. Again, in the triple exposure of the flashbacks he suggests the swiftness and unreality of life. The film is filled with bits of virtuosity, especially in the derangement and loss of memory sequences in which the villain sees distorted visions of the girl, and a partial insanity is suggested by a mere technical device. Such films as this take the taboo off the cinema as a medium incapable of psychological expression.

(Moviemakers would make another positive nod towards A Million Bid in an article on set design by legendary critic Harry Alan Potamkin, posthumously published in 1937.)

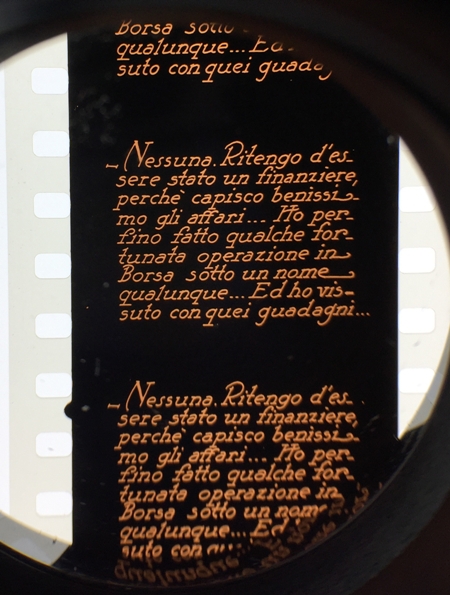

Unfortunately, any attempt we might make in evaluating A Million Bid is necessarily tentative and incomplete. All surviving copies of the film derive from a single Italian release print, which is linguistically and chromatically distinct from the American release. The film is tinted in a variety of colors in the Italian copy, though contemporary practice in America would likely have rendered a final release print in straight black and white. Additionally, contemporary advertisements suggest that the original American release of A Million Bid featured a Vitaphone score, though no copies of the discs appear to survive.

Above all, there’s the matter of the Italian intertitles, which are graphically handsome and compelling in their own right. Had the American titles survived, they would be bog standard Warner Bros. typeface and layout, no different from any other film the studio released in 1927. So ultimately we’re left with a specific variant of A Million Bid, rather than some pure rendition of the ‘definitive’ film as seen by American audiences. That’s a positive thing, as the Italian version works as a thing unto itself; trying to create an approximation of the American version by, e.g., replacing the Italian titles, would yield something of less authenticity rather than more.

Still, keeping the Italian version intact and as-is raises some logistical problems when presenting A Million Bid to modern audiences. We will be doing performing a live translation of the Italian intertitles at our screening, but there remain substantial questions about the reliability of the Italian translation, which may or may not accurately reflect the gist of the American titles. The Library of Congress provided a literal translation of the Italian intertitles, but it rarely captures the idiom of a Warner Bros. picture from 1927.

Some translation issues that seem like nitpicks actually have profound consequences for appreciating and understanding A Million Bid. When Warner Oland’s uncouth millionaire Geoffrey Marsh re-appears halfway through the film, washing up on the beach with no memory of his former life, the intertitles identify him as “signor Del Mare.” The first I saw A Million Bid at Cinefest nine years ago, this was translated as “Mr. Sea.” The LoC translation renders it more poetically as “the Stranger from the Sea.” But how was his character actually described to American audiences in 1927? (The “signor Del Mare” name pops up about a dozen times in the Italian version, which treats it as the amnesiac’s proper name.)

Mike Quintero, one of the Film Society’s greatest advocates and its most tireless freelance researcher, tried to get to the bottom of this issue with me, but we found it surprisingly difficult to confirm how this character was positioned for American audiences. Trade reviews and synopses, which can usually be relied upon to settle questions like this, referred only to Oland as “Geoffrey Marsh,” but not “Mr. Del Mare” or “The Stranger from the Sea” or anything like that. A few contemporary reviews refer to a “wandering” character, but none go so far as to call him “The Wanderer.”

A 1928 review of A Million Bid in the Brisbane Courier calls the amnesiac “Monsieur de la Mer” and describes him as a presumptive Frenchman. Assuming that the English titles were not remade for the Australian release, that would strongly suggest that “Monsieur de la Mer” was used in the now-lost American version. (The original 1908 Cameron play used “Monsieur de la Mer,” too, and explained that the character washed ashore on the Southern coast of France—a geographic detail absent from the surviving portion of the Italian version, which is missing several minutes.) And yet, the Australian review also refers to Malcolm McGregor’s character as “Dr. Loring Brent”—the name used in the 1914 Vitagraph version, not the “Dr. Robert Brent” that every other contemporaneous review of the ’27 version confirms. Did the Australian paper just dust off the synopsis they published in 1914? Can we trust their attribution of “Monsieur de la Mer”?

This seemingly insignificant detail exemplifies the depths of mysteries that still remain with even a ‘minor’ film like A Million Bid. If we can’t identify a character’s name with much certainty, what else are we missing?

Chicago Film Society screens A Million Bid at the Music Box Theatre on Saturday, April 21, with live organ accompaniment by Dennis Scott. The 35mm print appears courtesy of the Library of Congress. Original research has been made possible by Lantern, ProQuest, and Google Books.