In 1967, the newly-formed American Film Institute released a preliminary list of 150 significant feature films that were considered endangered, already lost, or thought to survive only in substandard copies. Lewis Milestone’s 1931 adaptation of The Front Page was among the titles at risk.

In 1967, the newly-formed American Film Institute released a preliminary list of 150 significant feature films that were considered endangered, already lost, or thought to survive only in substandard copies. Lewis Milestone’s 1931 adaptation of The Front Page was among the titles at risk.

Based on the reviews that greeted The Front Page in 1931, it’s sobering to recognize that the survival of such a highly-regarded film could be in doubt scarcely four decades later. To put that in perspective, it would be as if no one could readily ascertain whether a single copy of a film like Reds or Atlantic City still existed in 2017.

Admiration for The Front Page was professed in publications high-brow, low-brow, and every brow in between. The Chicago Tribune’s spectral critic Mae Tinee proclaimed that “Lewis Milestone’s direction is the last word in snap: lines click, photography and sound are all to the good. What this production lacks in nobility it makes up for in ‘It.’” Writing in Vanity Fair, Harry Alan Potamkin rhapsodized that “Milestone’s contribution in The Front Page is the first American contribution to the ‘philosophy’ of the sound-sight cinema. It puts forth the principle of pace set by the verbal element. The film itself is a tour de force, a vehicle which by its speed makes a superficial cargo appear profound.”

The Front Page earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture, too, but the passion aroused by the film was perhaps best captured by Pare Lorentz’s column in Judge:

With no regard whatsoever for the ladies’ clubs, the children’s aid societies, or the censors and Will Hays, Howard Hughes has made the most rip-roaring movie that ever came out of Hollywood. “Front Page” was a hilariously bawdy play with shotgun dialogue, but that is not important; movies have been from plays before, and seldom have they retained such raucous humor as that supplied by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. Front Page, regardless of its antecedents, is an extraordinary movie, and I advise you to see it before Mr. Hays, Mr. Akerson, or the Republican Committee on Humor burn all the available prints . . . .

I have seen several thousand movies in my day, but I never saw an audience laugh and cheer as it did on this occasion, and even the ushers caught the infection and assumed a sort of to-hell-with-you attitude that was nothing short of shocking . . . .

Some producers contend the public will not stand for it—they ought to watch the public fight to hear Front Page. Truth is, a few ministers and old women will not stand for it, and the producers have allowed themselves to be whipped into submission . . . . Here is one movie worth a fight.

Based on a review like that, who wouldn’t want to see The Front Page?

When The Front Page re-surfaced in the early 1970s thanks to a repatriation from the East German national archive, it was well-received by film historians and pre-Code cognoscenti but did not quite justify the fervor of the original reviews.

Little did we know that the version of The Front Page we’ve been watching since the 1970s was not the same one that fired up Tinee, Potamkin, and Lorentz. The East German copy at the Library of Congress was made from a foreign negative, with different takes and slightly different dialogue. The original American release version finally surfaced last year thanks to the efforts of the Academy Film Archive and the Film Foundation.

Little did we know that the version of The Front Page we’ve been watching since the 1970s was not the same one that fired up Tinee, Potamkin, and Lorentz. The East German copy at the Library of Congress was made from a foreign negative, with different takes and slightly different dialogue. The original American release version finally surfaced last year thanks to the efforts of the Academy Film Archive and the Film Foundation.

We talked to Heather Linville, Film Preservationist at the Academy Film Archive, about the rediscovery and restoration.

KW: I first saw The Front Page maybe ten years ago on TCM, in a very soft transfer of dupe print. Finally getting a chance to see the Library of Congress print a few years later was a revelation–it gave me a much firmer grasp on the film’s rhythmic and visual strategies. I didn’t think that source could be bettered. So, what was the initial goal of working from the Hughes print? Did you have any inkling that it was a different version of the film?

HL: In 2014, the Academy Film Archive received the Howard Hughes Collection from the University of Las Vegas, College of Fine Arts, Department of Film. This collection of moving image and audio material encompasses many of the titles produced by Hughes in the 1920s and 1930s under his production company Caddo Co., Inc. This acquisition includes a 35mm composite safety print of The Front Page. [A composite refers to a print that contains both the picture and optical soundtrack – Ed.]

After a detailed inspection of the element, we determined that the print was in excellent physical condition and the image quality was very good. The print was made at Consolidated Film Industries (CFI) in 1970. Paper records at UNLV indicated that the lab was instructed to “not return” the original nitrate camera negative once the print had been struck. Based on the inspection and documentation, we believed the safety print was made from the camera negative and would yield improved image and sound quality when compared to the Library of Congress source. Mike Pogorzelski (Director of the Academy Film Archive and co-supervisor of this restoration) and I approached our colleagues at The Film Foundation with a proposal for a 4K digital restoration. They agreed this was a worthwhile project, which resulted in the archive receiving a grant to move forward. We did not know at the time that this was a different version and what a surprise we had in store for us.

KW: At what point did you realize that the Hughes print represented the original American release version of The Front Page? In all that I’d read about the film over the years, I always assumed that the version floating around was the American version. How did you establish that the Hughes print was the bona fide American version, rather than, say, the British cut?

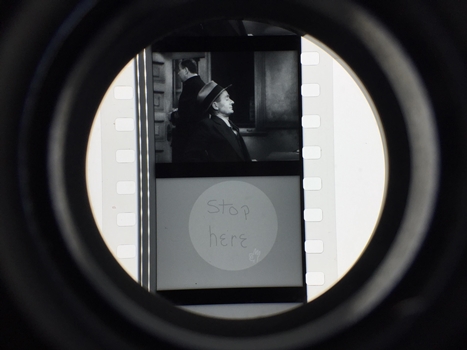

HL: The discovery of the different versions occurred during a test scan of the 35mm Hughes print. While the print was in excellent physical condition, there was one shot at the end of reel 4 that appeared to be a replacement. It was several generations away from the rest of the print. It was underexposed and very grainy. The original negative was likely damaged here and a replacement section was cut in. We also scanned the same shot in the Library of Congress (LC) source, also a 35mm safety print. The intention was to test both and see if the quality of this particular shot in the LC print was a better source to use for the restoration. As Mike and I watched the test, we noticed that while both shots depicted the same action, they were different takes. The lines of dialogue were the same, but the camera location was different and the length of the two shots was slightly different. We tested and compared other shots and ultimately discovered that every single shot in both elements was different. Even the dialogue was different in many shots.

To get to the bottom of it, I went to the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library where the Lewis Milestone papers reside. Within the collection are the production files for The Front Page. Listed on a budget summary were the detailed costs for three camera negatives. One for domestic distribution, another for UK distribution and what was identified as a “general foreign” version. This confirmed that the production of The Front Page had followed the practice of creating multiple camera negatives, a holdover from the silent era. We also learned from our colleagues at LC that the Library’s 35mm safety print was received as part of a trade with the East German Film Archive in the early 1970s, giving support to the theory that LC’s material represents the general foreign version. When we began to compare the Hughes print and LC print at the micro level, the differences became clear. The Hughes print contains the best performances and camera moves. It also reflects the most attention to cutting, pacing and timing when compared to the LC print. There were changes to the dialogue to accommodate cultural references that would have made sense to Americans but perhaps not to international audiences. Other differences in dialogue and action cater to American censorship regulations.

KW: I’m assuming that you’ve probably seen this film more times than you’d like to count at this point. But as a viewer, does the chance to see the American version change anything about film for you? Did your estimation of the filmmaking change after seeing this version?

HL: In our research into the different versions, Mike and I learned that all of the public domain videocassettes, DVDs, Blu-rays and web copies originate from the Library of Congress source. The Hughes print and the Academy Film Archive’s subsequent digital restoration reveal Lewis Milestone’s most authentic representation of The Front Page. For an early 30s talkie, it is sharp, witty and sophisticated beyond its time. While the version represented in the LC source demonstrates this as well, it is even more refined in the domestic version. It is this domestic version that earned the film three Academy Award nominations for acting (Menjou), directing and outstanding production.

KW: There are some subtle differences in dialogue and shot choice, but I think most audiences who’ve seen the film before will be immediately impressed by the clarity of the sound. You had the opportunity to work from the original Vitaphone stampers. I can’t recall another restoration that had access to that kind of sound element. Can you talk about that experience?

HL: The Front Page was released during the transition from sound on disc to sound on film. Included in The Front Page material in the Howard Hughes Collection was a complete set of metal master stampers as well as a few additional discs representing state censored versions for Pennsylvania and Ohio. These stampers were used to press the lacquer discs that went out with the distribution prints. For the restoration, we were fortunate to have two audio sources to work from; the variable density track on the 35mm safety print as well as the stampers, both representing the domestic version.

Capturing the audio from the discs is quite different than capturing from a record. Instead of a needle reading the sound in the groove like a record, the audio on a metal stamper is located on the ridge. Therefore, a bi-point needle is required to “ride the ridge” in order to capture the sound. There are only a few people in the world who have this obsolete needle. We turned to Doug Pomeroy, an audio engineer in Brooklyn who had the needle and a wealth of expertise. Doug was able to provide digital files made from the stampers to John Polito of Audio Mechanics. John and I listened to both sources and found the metal stampers didn’t have any of the common defects heard in optical tracks. The discs also had a higher frequency response than the optical source. While the audio from the discs was not perfect, it was a better source than the optical track, so they became the primary source for the audio restoration.

Capturing the audio from the discs is quite different than capturing from a record. Instead of a needle reading the sound in the groove like a record, the audio on a metal stamper is located on the ridge. Therefore, a bi-point needle is required to “ride the ridge” in order to capture the sound. There are only a few people in the world who have this obsolete needle. We turned to Doug Pomeroy, an audio engineer in Brooklyn who had the needle and a wealth of expertise. Doug was able to provide digital files made from the stampers to John Polito of Audio Mechanics. John and I listened to both sources and found the metal stampers didn’t have any of the common defects heard in optical tracks. The discs also had a higher frequency response than the optical source. While the audio from the discs was not perfect, it was a better source than the optical track, so they became the primary source for the audio restoration.

KW: You worked from a print struck from the (now lost) original camera negative back in the 1970s, which meant that many qualities of the restored version would be dictated to some degree by the lab work that CFI performed decades ago. How did the source element dictate the workflow chosen by the Archive? Were there any other considerations?

HL: The source element did dictate the workflow because once we discovered we could not use the LC print to replace that dupey shot from reel 4, we knew that the two sources were different versions. Any hurdles we came across in the Hughes print had to be dealt with as best as we could, given that we did not have a secondary source to work with. There are a few areas in the source where there are chemical stains built into the print from the original negative. The 35mm source print was wet-gate scanned at 4K by ImagePro in Burbank. MTI Film in Hollywood, who did the image restoration, used digital techniques to minimize the residue without impeding on image structure.

KW: The Archive made a 35mm film-out of the 4K restoration of The Front Page. Other films in the Hughes collection, such as Cock of the Air, screened in DCP. How does the Archive determine when a film-out is justified and when a DCP is sufficient?

HL: The decision to proceed with a film-out is assessed on a project-by-project basis. For instance, a film-out was not part of the archive’s recent restoration of Hoop Dreams (a collaboration with UCLA Film & Television Archive and Sundance Institute) because it was originally shot on video. The Academy Film Archive’s recent recreation of the uncensored version of Cock of the Air is a very unique project that incorporated modern voice-over performances to fill in lost censored dialogue. We created a DCP that has a small icon that appears in the bottom corner of the frame to indicate when a censored scene contains contemporary voice-overs, music and effects. To film-out this title properly would require the creation of two negatives and subsequent prints, a set of elements which contains the icon and a set that does not. While the archive could take this step, it would cost at least $100,000. We feel it is more strategic to use those resources to preserve other at-risk titles.

The Front Page restoration was funded through a generous grant from The Film Foundation, an organization that is committed to ensuring all digital restorations of titles originating on film include a film-out (in this case a 35mm digital intermediate negative and 35mm prints with restored sound track). These new film materials are in addition to the DCP for theatrical presentation and DPX files of both the “raw” 4K scans and restored files, which represent the digital archival assets.

Chicago Film Archive presents the local premiere of the Academy Film Archive’s restoration of The Front Page at the Music Box Theatre on Monday, January 23. Advance tickets can be purchased here.