Now that the film vs. digital debate is winding down, the National Association of Theater Owners has turned its attention towards more pressing matters. Last month the exhibitor’s trade group issued new guidelines for movie trailers and related promotional material, effective October 2014. It was a canny move, seizing upon public sentiment that “trailers are too damn long” and thus earning ink for NATO in publications like RedEye that would typically ignore its pronouncements. (When you share an acronym with the instantly recognized North Atlantic Treaty Organization, it’s hard to get mainstream press coverage. Then again, as an industry trade group, perhaps you don’t want the sunlight in the first place.)

Now that the film vs. digital debate is winding down, the National Association of Theater Owners has turned its attention towards more pressing matters. Last month the exhibitor’s trade group issued new guidelines for movie trailers and related promotional material, effective October 2014. It was a canny move, seizing upon public sentiment that “trailers are too damn long” and thus earning ink for NATO in publications like RedEye that would typically ignore its pronouncements. (When you share an acronym with the instantly recognized North Atlantic Treaty Organization, it’s hard to get mainstream press coverage. Then again, as an industry trade group, perhaps you don’t want the sunlight in the first place.)

The new NATO guidelines, which are completely voluntary, mandate that movie trailers run no longer than two minutes and be released no more than five months before than the movie that they’re promoting. (Trailers are presently around two and half minutes apiece.) Each distributor will qualify for two exemptions per year, though these exceptional trailers cannot be any longer than three minutes. NATO’s latest also clamps down on “direct response prompts (QR codes, text-to, sound recognition, etc.)” in trailers and endorses practices that most theaters abide by already, such as assuring that age-appropriate trailers accompany each feature so that Dallas Buyers Club isn’t pitched at the Frozen crowd.

NATO’s new marketing directives also encompass more than just trailers. Posters and standees will not be displayed more than four months prior to a film’s release. Revealing, but little remarked upon, is NATO’s decree that studio marketing personnel and on-site auditors should identify themselves to theater management and meet a minimum standard of courtesy and professionalism (!)

It’s easy to be cynical about new trailer guidelines. The big theater chains represented by NATO want their customers to have a good time at the movies, but a highly regimented and regularized good time. Theater owners typically prefer shorter shows because it allows them to hold more screenings per day and profit from greater audience turn-over. (If you require a reminder of how bottom-line-oriented the NATO operation is, check out the trade group’s talking points on the perils of raising the minimum wage and the burden of providing health insurance for theater employees. NATO’s position paper on the Employee Free Choice Act has vanished following a website redesign, though I will not soon forget NATO’s memorable description of card check as “union elections by ambush.”)

Shaving thirty seconds off each trailer sounds modest and it certainly won’t allow theater owners to fit in an extra show. One suspects that the guidelines represent little more than a shallow show of solidarity with trailer-wary audiences. If NATO really wanted to improve the moviegoing experience, they could regulate or curtail the pre-trailer advertisements that practically begin the moment the previous show ends!

Shaving thirty seconds off each trailer sounds modest and it certainly won’t allow theater owners to fit in an extra show. One suspects that the guidelines represent little more than a shallow show of solidarity with trailer-wary audiences. If NATO really wanted to improve the moviegoing experience, they could regulate or curtail the pre-trailer advertisements that practically begin the moment the previous show ends!

This presumptive antipathy towards trailers is hardly universal. As our projectionist and programmer Julian Antos notes:

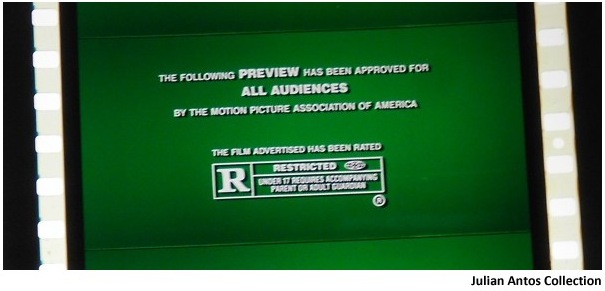

People who complain about trailers being too long (or too numerous) do not love cinema. They may love “movies”—a term which here means any moving picture, on any screen, anywhere—but they’re the same people who have the gall to ask how long a movie is (the same question as “are we there yet?”) or what a movie is about (a movie is not “about,” a movie “is!”). They compare films to the books they’re based on, and don’t stay until the very end of the credits. People who complain about trailers have no knowledge of the care that went into bringing them to the screen. And they have no love for the beautiful MPAA green band. ’Tis a beacon of the cinema! Everyone I know who WORKS at a movie theater LOVES trailers. Unfortunately, I don’t have a good sense of how the public feels about them.

And there’s the rub. Before we get exercised about jackbooted thugs dictating the length of our trailers, it’s important to remember that public recognition of trailers is a relatively recent phenomenon. For many years, “trailer” was an advanced form of industry lingo for something better known to the general public as “coming attractions” or “the previews.” (Ever contrarian, theater types preferred “prevues” when they deigned to use the popular vernacular.) Trailers were so named because they often trailed the feature, a kind of chaser from the days when movies were screened continuously and audiences wandered in and out as they pleased. (This naturally raises the question: are trailers meant as stirring promotional material or something just irritating enough to rouse the sleeping drunks from their seats after the last show of the evening? In the multi-valence world of cinema exhibition, can it not be both?)

The shift in audience awareness of trailers reflects broader trends in media consumption over the last fifteen or so years. With trailer watchers migrating from Entertainment Tonight to the balkanized pastures of the internet, the casual moviegoer has merged with the superfan. Likewise, the proliferation of the audio commentaries and supplemental material—once a pricey, elitist laserdisc fixture—has made every DVD buyer a potential expert on her favorite movie. Television viewing has followed a parallel course; the constant churn of undifferentiated weekly content is now analyzed in minute detail, with formerly arcane, insider signifiers like the episode title cited by everyone. (Here, too, DVD has been crucial, because the proliferation of season-by-season box sets trains viewers to regard television in industry terms, as a cohesive, long-form narrative instead of ephemeral “Must See TV.”) In all cases, the fans have become deeply embedded in the product and the process.

The shift in audience awareness of trailers reflects broader trends in media consumption over the last fifteen or so years. With trailer watchers migrating from Entertainment Tonight to the balkanized pastures of the internet, the casual moviegoer has merged with the superfan. Likewise, the proliferation of the audio commentaries and supplemental material—once a pricey, elitist laserdisc fixture—has made every DVD buyer a potential expert on her favorite movie. Television viewing has followed a parallel course; the constant churn of undifferentiated weekly content is now analyzed in minute detail, with formerly arcane, insider signifiers like the episode title cited by everyone. (Here, too, DVD has been crucial, because the proliferation of season-by-season box sets trains viewers to regard television in industry terms, as a cohesive, long-form narrative instead of ephemeral “Must See TV.”) In all cases, the fans have become deeply embedded in the product and the process.

As with so many things, film collectors were here first. I know of no film collector who looks down upon trailers, and many seem to harbor almost as much (or perhaps more?) affection for these mini-movies as they do regular features. Civilian audiences complain of endless trailers at the movie theater; film collectors always want more. They spend hours splicing together reels and reels of the stuff, hoping to impress audiences with the perfect trailer compilation.

Trailers also pose a practical advantage: you can fit twenty or thirty in the shelf space required for a simple feature. In some cases, they’re necessary adjuncts to the feature, as when a trailer presents scenes or dialogue absent from the final cut of the movie itself. (The Master is a good recent example: “I know you’re trying to calm me down but just say something that’s true” may be one of Joaquin Phoenix’s most emblematic, moving lines, but it survives only in the trailer.) The trailer may also represent something aesthetically better than the finished film, such as IB Technicolor trailers advertising features that were released only in fade-prone Eastmancolor or 70mm trailers for features that circulated only in 35mm. (The green band at the top of this post comes from a 70mm trailer for Unforgiven.)

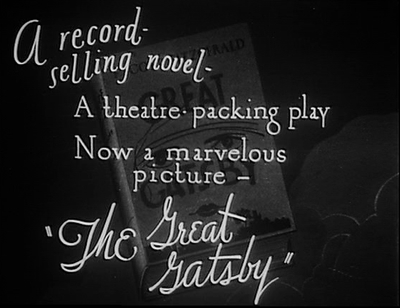

Another collector’s defense of trailers: they sometimes survive long after the pictures they promoted have vanished, leaving the disreputable trailer as our only glimpse at important pictures like Ernst Lubitsch’s The Patriot or Herbert Brenon’s contemporaneous rendering of The Great Gatsby. Both fragments are available on the National Film Preservation Foundation’s More Treasures from the Film Archives DVD box set.

Another collector’s defense of trailers: they sometimes survive long after the pictures they promoted have vanished, leaving the disreputable trailer as our only glimpse at important pictures like Ernst Lubitsch’s The Patriot or Herbert Brenon’s contemporaneous rendering of The Great Gatsby. Both fragments are available on the National Film Preservation Foundation’s More Treasures from the Film Archives DVD box set.

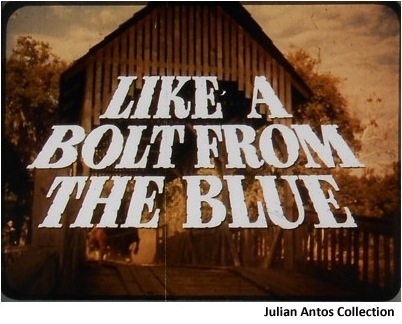

The pride that film collectors vest in their trailer reels is touching. Any schmuck can invite you to his basement to watch a movie; only a master can curate a varied program of trailers. At the annual Cinefest convention, Ray Fiola habitually presents an hour-long block of trailers on 16mm, often arranged thematically or by studio. Jack Theakston presents an equally storied mix of trailers, snipes, and shorts at Capitolfest in Rome, New York. And Jake Perlin recently capped an exhaustive Jean-Luc Godard retrospective with a 35mm JLG trailer show, with many of the prevues cut by the cantankerous Swiss.

I doubt that NATO can even conceive of the trailer as a platform for Godard’s disjunctive art, but the trade group’s recent guidelines arbitrarily circumscribe and limit the form for everybody. Two minutes? Did audiences ever complain about the six-minute trailer for Psycho wherein Hitchcock offered a guided tour of the Bates Motel? What about the five-minute In Harm’s Way trailer that featured Otto Preminger bellowing directions from a submarine platform. (Preminger’s movie came out roughly a quarter-century after the Pearl Harbor bombing that it depicts. Can we imagine a similarly irreverent trailer about, say, the Challenger explosion today?)

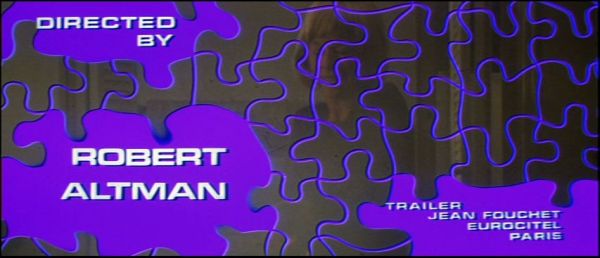

It’s easy to elevate the trailer to sanctified movie art when an undisputed auteur is involved. (For that matter, there’s also Orson Welles’s highly unconventional trailer for Citizen Kane and his extended prevue for F for Fake, or the wonderful Lubitsch-hosted trailer for The Shop Around the Corner.) Much rarer is an acknowledgement of trailer makers as artists themselves. An especially elaborate and arty preview for Robert Altman’s Images credits Jean Fouchet as the author of trailer, but it’s the exception that proves the rule. (Trailer voice-over talent received an unexpected, and fictional, showcase in last year’s feminist rom com In a World …)

It’s easy to elevate the trailer to sanctified movie art when an undisputed auteur is involved. (For that matter, there’s also Orson Welles’s highly unconventional trailer for Citizen Kane and his extended prevue for F for Fake, or the wonderful Lubitsch-hosted trailer for The Shop Around the Corner.) Much rarer is an acknowledgement of trailer makers as artists themselves. An especially elaborate and arty preview for Robert Altman’s Images credits Jean Fouchet as the author of trailer, but it’s the exception that proves the rule. (Trailer voice-over talent received an unexpected, and fictional, showcase in last year’s feminist rom com In a World …)

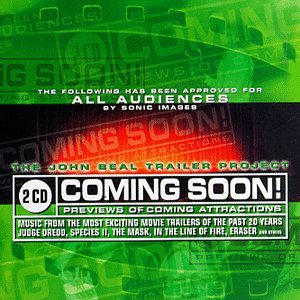

Anonymous, too, are the composers of trailer music cues, which are often written and recorded long before the film’s official score is complete. The prolific trailer composer John Beal broke the mold and effectively reclaimed his contributions when he released a 2-CD compilation on the Sonic Images label in 1998. Much more than muzak, Coming Soon: The John Beal Trailer Project functions as an encyclopedic, shape-shifting revue of pop styles, not unlike the Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs.

Anonymous, too, are the composers of trailer music cues, which are often written and recorded long before the film’s official score is complete. The prolific trailer composer John Beal broke the mold and effectively reclaimed his contributions when he released a 2-CD compilation on the Sonic Images label in 1998. Much more than muzak, Coming Soon: The John Beal Trailer Project functions as an encyclopedic, shape-shifting revue of pop styles, not unlike the Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs.

Perhaps the anonymity of trailers constitutes their secret weapon. Since no one expects them to function like capital-M Movies, they have more leeway in rhetoric and scope. The original trailer for The Grapes of Wrath addresses the reception of the novel and the ginned-up anticipation of the movie version—peripheral topics that exist beyond the strictly narrative preoccupations of the feature itself. Likewise, the trailer for Night Nurse makes explicit the premise and promise of the movie—that the secret world of nurses rates as a roiling national obsession, a racket just waiting for its top to be blown clear off. At times, trailers even attempt a kind of pidgin autocriticism, as when Astor Pictures attempted to sell future art house favorite Last Year at Marienbad as a glorified movie of a choose-your-own-adventure novel.

Perhaps the anonymity of trailers constitutes their secret weapon. Since no one expects them to function like capital-M Movies, they have more leeway in rhetoric and scope. The original trailer for The Grapes of Wrath addresses the reception of the novel and the ginned-up anticipation of the movie version—peripheral topics that exist beyond the strictly narrative preoccupations of the feature itself. Likewise, the trailer for Night Nurse makes explicit the premise and promise of the movie—that the secret world of nurses rates as a roiling national obsession, a racket just waiting for its top to be blown clear off. At times, trailers even attempt a kind of pidgin autocriticism, as when Astor Pictures attempted to sell future art house favorite Last Year at Marienbad as a glorified movie of a choose-your-own-adventure novel.

Hollywood movies, even in our allegedly post-modern era, rarely address the audience directly, but trailers exist in a perpetual second-person state. The mode exalts in complicity, demands our engagement in an unashamed, smiling way. Prior to the 3D revival, trailers were the last bastion of an enlarged, aggressive form of cinema ballyhoo that recalls an earlier age of unfashionably forthright spectatorship.

Trailers possess an aesthetic, and a distinctive, legitimate one at that. We can conjure them out of the air. Consider this passage from Roger Ebert’s review of Entrapment:

Watching the film, I imagined the trailer. Not the movie’s real trailer, which I haven’t seen, but one of those great 1950s trailers where big words in fancy typefaces come spinning out of the screen, asking us to Thrill! to risks atop the world’s tallest building, and Gasp! at a daring bank robbery, and Cheer! as towering adventure takes us from New York to Scotland to Malaysia. A trailer like that would be telling only the simple truth. It also would perhaps include a few tantalizing shots of Zeta-Jones lifting her leather-clad legs in an athletic ballet designed to avoid the invisible beams of security systems. And shots of a thief hanging upside-down from a 70-story building. And an audacious raid through an underwater tunnel. And a priceless Rembrandt. And a way to steal $8 billion because of the Y2K bug. And so on.

It’s not uncommon to hear people, especially critics, complain that a finished film plays like little more than a trailer for itself, or perhaps the toy or video game tie-in that springs from it. Michael Bay takes flack for cutting his movie as if they were trailers, but I’ve still never seen a feature film that sustains the rhythmic precision, the spatiotemporal flexibility, or the anything-can-happen narrative buoyancy of the best trailers. The true ninety-minute trailer would be a radical cinematic event, and one I would very much look forward to.