Much has been written of the enormous strides made by genuinely independent cinema in recent years. In 2004, nearly every review of Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation cited its “budget” of $218 and touted its desktop iMovie roots as a harbinger of things to come. Theatrical distribution for no-budget personal documentaries didn’t last long. YouTube would launch within six months.

Much has been written of the enormous strides made by genuinely independent cinema in recent years. In 2004, nearly every review of Jonathan Caouette’s Tarnation cited its “budget” of $218 and touted its desktop iMovie roots as a harbinger of things to come. Theatrical distribution for no-budget personal documentaries didn’t last long. YouTube would launch within six months.

Nevertheless, digital moviemaking has been embraced as a uniquely democratic avenue, the kind of game-changer that fundamentally alters who makes and consumes media. The ease of digital production and dissemination cannot be denied, but neither should we assume that the film era presented insurmountable barriers to entry. If anything, the disappearance of analog workflows makes the achievements of the past all the more impressive. How did aspiring filmmakers ever master exposure, A/B roll cutting, synchronization, and magnetic sound recording? These technical hurdles were real, but they hardly stopped a flood of alternative media, dissident art, regional filmmaking, and genuine oddities from reaching the screen.

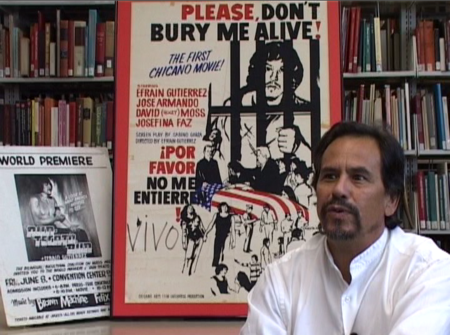

Efraín Gutiérrez is one of the least likely, most bewildering figures of the celluloid era. With minimal capital and technical experience, Gutiérrez managed to produce and distribute three features and one short film in the latter half of the 1970s—the first films to depict the Chicano community from the inside. The details of Gutiérrez’s career became the stuff of legend, particularly after the filmmaker’s 1980 disappearance. Some speculated that he’d been a drug runner or a hit man and financed his films through illicit means. The sympathetic critic Gregg Barrios made a case for Gutiérrez as a pioneering Chicano filmmaker while acknowledging the consensus view that his films were “sexist and racist diatribes that should be ignored and forgotten.”

When the scholar Chon Noriega finally tracked down Efraín Gutiérrez in 1996, more of the story emerged and it proved even more compelling the legend. “I won’t go into detail,” said Gutiérrez about his first feature Please, Don’t Bury Me Alive!, “but I did some bad things to raise some money.” Wildly underestimating the cost of making a feature film, he also hustled money from Trinity University and the American Lutheran Church. On credit, he blew up the 16mm original to 35mm for theatrical exhibition. Upon finding that no theater wanted to show it, Gutiérrez used assorted debts to establish further lines of credit and rent out a theater and advertise the film in local media.

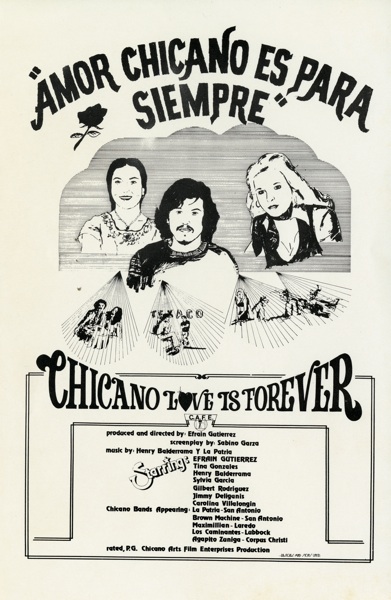

Please Don’t Bury Me Alive grossed $20,000 in the first week at a single four-wall situation and eventually earned $300,000 after playing in Spanish-language theaters throughout the Southwest. After this success, Gutiérrez sold distribution rights to a Mexican distributor who absconded with all the 35mm prints. Gutiérrez plowed ahead with another feature, Chicano Love is Forever. He pre-sold distribution rights and promised his financiers a love story. Instead, he made a bleak but realistic depiction of the challenges facing a young Chicano couple.

Through Noriega’s efforts, Gutiérrez’s films have been restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Though all three features and the short La Onda Chicana have been available from UCLA for over a decade, they have not circulated much. An article published by the San Antonio Current in conjunction with one recent San Antonio screening indicates one reason why:

It’s easy to dismiss the films of Efraín Gutiérrez. His movies are rough, unpolished, and lacking those things cinema experts consider, well, good. If Ed Wood was “the worst director of all time,” you can almost say Gutiérrez is a Chicano Ed Wood with a political conscience — bad acting, weak writing, and lousy camera work. Gutiérrez knows it, but he smiles and takes no offense.

“Three!” he says, holding up three fingers on his right hand. “Three takes! I never took more than three takes!” He’s not bragging about it, but he’s not about to apologize either.

Going into Gutierrez’s films expecting technical finesse or anything like conventional narrative is a mistake. But their existence enriches and enlarges our sense of film history. That these films enjoyed substantial runs in the Southwest throws our notions of Hollywood hegemony into confused relief. Here is an attempt to depict a marginalized community with no concessions to the dominant culture. The dialogue freely switches between English and Spanish without subtitles in either language—presuming a bilingual audience, or a naturally empathetic one. They serve, too, as extraordinary documents of a political moment, when the assertion of Chicano identity was itself radical.

Articles on Gutierrez’s career are few and far between. There’s Gregg Barrios’s mid-1980s career re-evaluation and there’s another brief profile from the My San Antonio website, but the best source for information about Gutierrez remains Noriega’s moving and sincere tribute, ‘The Migrant Intellectual’ in the Spring 2007 issue of Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies.

Noriega serves as the Director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. I interviewed him earlier this week about Gutierrez’s filmmaking and its unique place in American culture.

KW: You made an effort to track down Efraín Gutiérrez’s films long before you had a chance to see them. How did you first hear about these films and what convinced you that they merited re-evaluation?

CN: I first heard about Efraín’s films in my interviews with other Chicano filmmakers when I was working on my dissertation around 1989-91. He was sort of a legendary figure who showed that Chicanos could make independent feature films working outside Hollywood. He wrote, directed, starred in, and distributed three feature films in the late 1970s—working with his wife at the time, Josie Faz, and other local artists in San Antonio—and then he disappeared.

CN: I first heard about Efraín’s films in my interviews with other Chicano filmmakers when I was working on my dissertation around 1989-91. He was sort of a legendary figure who showed that Chicanos could make independent feature films working outside Hollywood. He wrote, directed, starred in, and distributed three feature films in the late 1970s—working with his wife at the time, Josie Faz, and other local artists in San Antonio—and then he disappeared.

I began to find traces of his history through articles published at the time in local magazines and newspapers in South Texas. Each time I went to CineFestival at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio, I would ask people I met if they had heard of Efraín Gutiérrez. The legend continued to grow, but I could not find the person himself. Then one day in late 1996, I came home to find a message from Efraín. Now he was looking for me!

KW: You spent three years working with Efraín to recover these films. Where were the films found and what elements survived? In what condition did you find them?

CN: When he called, Efraín had just recovered a 16mm print of Please, Don’t Bury Me Alive! from where he had stored it in a relative’s garage. The print had been wrapped up and stored inside a garbage can, and was actually in fairly good shape. But Efraín had just screened it and the print had broken in a few places. I urged him to stop screening the print and place it in an archive so it could be restored and preserved.

What happened next astounded me and set us on a course to recover all his films, and to become good friends in the process: Efraín loaded up the print in his car, along with his family and his daughter’s friend, and drove from San Antonio to Los Angeles, delivering it for deposit in the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Subsequently, Efraín was able to locate a 35mm print of Run, Tecato, Run that he had given to one of the investors for the film; and I worked with the UCLA Film & Television Archive to locate the original 16 mm. color reversal AB rolls and the original 16 mm. master sound mix for Amor Chicano Es Para Siempre. These had been left in the lab Efraín used, but when the lab was sold, these materials became “hidden” within the larger holdings of the new owner. This film became the only one for which we were able to locate original elements.

KW: Academics and archivists often operate on different time scales, with very different goals and priorities. How did you manage to balance the two worlds and work with UCLA Film & Television Archive to assure the proper preservation of these films?

KW: Academics and archivists often operate on different time scales, with very different goals and priorities. How did you manage to balance the two worlds and work with UCLA Film & Television Archive to assure the proper preservation of these films?

CN: You do need to find a balance, since they are different professional cultures, and also because nothing gets preserved otherwise. Fortunately, I have had the good fortune to have mentors committed to archival practice. My dissertation director, Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, was the ideal role model of an academic who saw the community as a site of knowledge production and archival resources. Roberto Trujillo, now Head of Special Collections at Stanford University, hired me to work on new acquisitions to their Mexican American Collection. In the process, I learned a lot about archival preservation and access.

When I was hired as an assistant professor at UCLA, Robert Rosen was both chair of the Department of Film and Television and director of the Film & Television Archive. More than anyone, he helped me understand the issues, ethics, and processes involved in order to preserve these films.

KW: Anyone who’s grown up watching Hollywood films is instantly familiar with its patronizing stereotypes of indigenous culture. But Gutiérrez was also reacting against the clichés of the Mexican exploitation films that dominated Spanish-language theaters in the American Southwest. Can you describe these films and the picture they offered of Chicano identity?

CN: Well, both Hollywood and the Mexican film industry responded to the Chicano civil rights movement in similar ways, converting its demands for social equity into the basis for exploitation films. In the U.S., these were mostly youth-oriented gang films. The most notorious involved teen heart throb Robbie Benson as a Chicano gang member….

In Mexico, the focus was more on the border as a lawless space, involving gangs, drugs, and so on. Gutiérrez was reacting to these portrayals, but he also used them to his advantage in interesting ways. In 1973, Efraín completed worked as an extra on De sangre chicana (Of Chicano Blood), a film being shot in San Antonio. The film, one of a number of Chicano exploitation films produced by the Mexican film industry in that decade, disillusioned him about Mexico as an alternative to Hollywood, especially because the Chicano extras were segregated from their Mexican and Anglo counterparts.

Frustrated, Efraín happened to stumble across the canisters of undeveloped footage in the lobby of the hotel where the production crew was staying. He hid the canisters and then approached the producers, offering them his help in finding the canisters in exchange for an opportunity to “shadow” the director and cinematographer. He used that experience in order to round out his ad hoc education in filmmaking. One thing about Efraín is his determination to learn by any means necessary in order to break down barriers for Chicano filmmakers.

KW: Did Gutiérrez’s films ever play beyond theaters in the Southwest? Did they travel to other Spanish-language communities?

KW: Did Gutiérrez’s films ever play beyond theaters in the Southwest? Did they travel to other Spanish-language communities?

CN: While Gutiérrez’s films had an obvious appeal in South Texas, he did screen them in California and the Midwest. Interestingly, the films became very popular among Chicanos in prisons around the country. He was sort of the Chicano “Johnny Cash” of American cinema! Because the films were gritty and realistic, they offered hope rather than fantasy.

KW: How have modern audiences reacted to Gutiérrez’s films? Are they regarded as political artifacts of a tumultuous, bygone era or films that still speak to conditions today?

CN: These films are sui generis, so it is hard to relate them to other works. Efraín was self-taught as a filmmaker, drawing heavily from his background in community-based Chicano theater, his relationships with Conjunto musicians, and bilingual dialogue that reflected local practice. He also created a unique business model, relying on individual investors, exhibition contracts with Spanish-language theaters (which were losing ground to television), and promotion through local radio and newspapers.

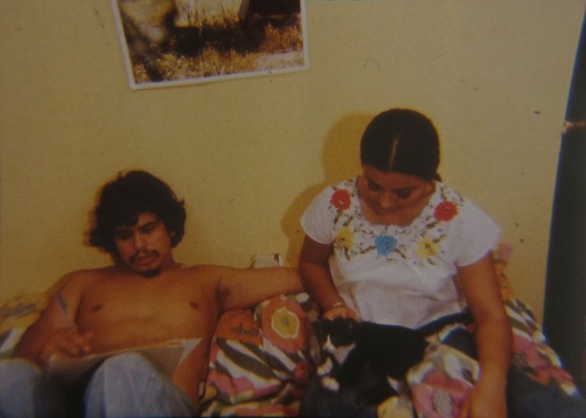

But more than anything, these films spoke to a Mexican American audience that had never seen itself on the silver screen. Good portions of the films consist of entire musical performances as well as long observational shots of local settings. In a sense, the documentary aspect of the films rivals the narratives, which can be strange for viewers used to Hollywood fare, but provides a fascinating window into another time and place. There are no happy endings, or clear-cut good guys versus bad guys, but rather an attempt to engage with the day-to-day experiences and culture of the films’ audience. It is important to remember that these are extremely low-budget films that are essentially creating their own audiovisual language for a Mexican-American or Chicano audience in the 1970s.

• • •

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will screen Amor Chicano Es Para Siempre on June 12 at the Patio Theater. The restored 35mm print appears courtesy of the UCLA Film & Television Archive and will be preceded by Efrain Gutierrez’s short film La Onda Chicana (The Chicano Wave). Preservation of Amor Chicano Es Para Siempre was funded by the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States. Preservation of La Onda Chicana was funded by the Ahmanson Foundation in association with the Sundance Institute and the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States.

This screening is offered in conjunction with portoluz’s Old and News programming. Special thanks to Efraín Gutiérrez, Chon Noriega, Steven Hill, Marguerite Horberg, Peter Kuttner, and Demetri Kouvalis.