“Sometimes miniature electric train cars simply will not stay coupled. At some crucial tunnel, curve, or grade, the locomotive charges forward, leaving uncoupled cars behind and possibly derailed. It often seems that extra exertion at switches, curves, and grades has something to do with the uncoupling.

“Much, perhaps most, of the film footage that you project is coupled into “trains.” Like those miniature trains, films must stay coupled and on track through something like tunnels, curves, and grades, and switches. Therefore, couplings—let’s, of course, call them splices or joins—are crucial. Making good splices is one of your key responsibilities as a film handler. ”

— The Kodak Book of Film Care, 1st Edition, 1983

Films on Fire

S ometimes I’m afraid that the migration of film writing from the page to the blogosphere has made it more difficult for us to conceive of déclassé, orphan cinema. Can we access and understand the sense of complete aloneness that first-generation auteurists felt when championing Marnie or Red Line 7000 or 7 Women? Although Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes aggregate an instant consensus, the unruly infinity of film blogging assures that, somewhere, every film has an eager on-the-record advocate. No product is truly marginal and every ‘outrageous’ critical position has been spoken for. (See, for example, Zach Campbell’s apologia for Anna Faris.)

ometimes I’m afraid that the migration of film writing from the page to the blogosphere has made it more difficult for us to conceive of déclassé, orphan cinema. Can we access and understand the sense of complete aloneness that first-generation auteurists felt when championing Marnie or Red Line 7000 or 7 Women? Although Metacritic and Rotten Tomatoes aggregate an instant consensus, the unruly infinity of film blogging assures that, somewhere, every film has an eager on-the-record advocate. No product is truly marginal and every ‘outrageous’ critical position has been spoken for. (See, for example, Zach Campbell’s apologia for Anna Faris.)

At least this was my governing assumption until I met a teenage art student when I returned to my high school a few years ago. My reputation undiminished as the school’s reigning cinephile, a teacher thought to introduce me to another such up-and-comer. Our exchange was pleasant enough. I tried to feel out his taste.

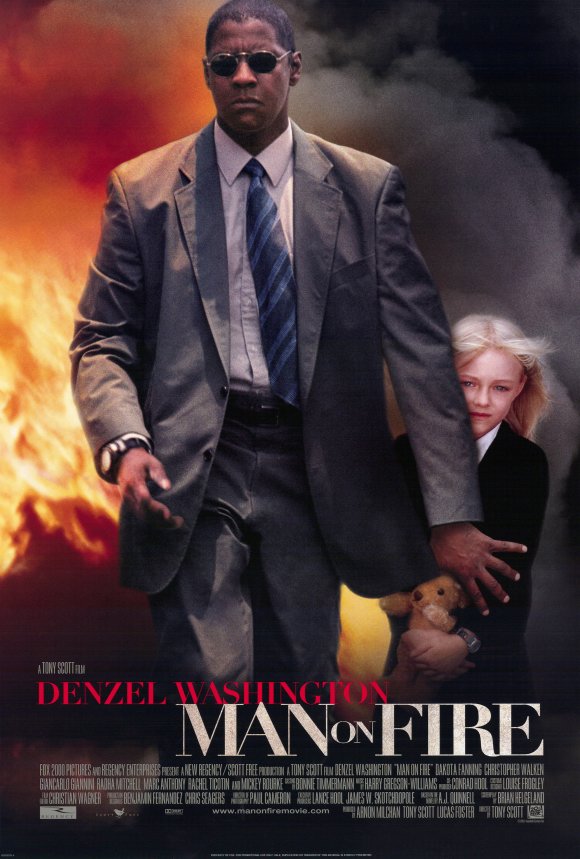

He proclaimed Tony Scott’s Man on Fire his favorite film ever.

The visceral disconnect I felt upon learning of this valuation is difficult to describe. He patiently described the technical virtuosity of the film, Scott’s attention to varied lens and film stocks, the fluidity of the montage, but I couldn’t keep up. I had never seen a Tony Scott film and was genuinely surprised to learn that Man on Fire had any popular following. It was common enough to hear young cinephiles rate Fight Club or The Matrix as a pinnacle of cinema, but this was entirely unexpected. I remembered the simple and literally flaming one-sheet for Man on Fire, but knew nothing of the film itself. Wasn’t this just another macho actioner with a standard-issue Denzel Washington performance?

One some level, it was electrifying to play the dowdy John Simon to this student’s upstart Andrew Sarris. I was twenty-two and already destined for the cinema compost bin, too old-fashioned to grok the underground’s new auteur. My progressive advocacy for Jia Zhangke and Wong Kar-wai immediately felt like calcified consensus. Was he crazy or was I?

I’m not prepared to answer that question, but he had a point about Tony Scott.

Stateless Art

After the pounding (and undeniably well-crafted) excesses of The Hunger, Tony Scott became a prototypical blockbuster director for producer Don Simpson. With Top Gun, he created official state art for a capitalist-democracy that thought itself above such things. Not only a recruitment film in itself, Top Gun provided an advertising template and aesthetic for all branches of the armed forces—a template, one might add, that survived the traumas of Afghanistan and Iraq stunningly intact.

Thus, for any socially-engaged film viewer, Scott’s name represented not only a certain strain of mindless entertainment gobbled up by the mass audience (from which we claimed to stand apart), but also a real political legacy with genuine culpability for extending and consecrating an ever-militarized, bipartisan international policy. Why should anyone get excited for the latest Tony Scott film?

I’ve never managed to sit through Top Gun, but the equally right-wing Man on Fire is a real piece of ugly work. In one scene, divinely-ordained counter-insurgency black ops expert Denzel Washington inflicts rectal torture upon a corrupt Mexican police official. Another half-dozen thugs are treated to humiliating and fatal ‘enhanced interrogations.’ (Cosmically, Man on Fire opened in theaters the week before revelations of appalling prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib gained media traction through 60 Minutes II and Seymour Hersh’s reporting in The New Yorker.) Like a morally unclouded variation on Dirty Harry, Man on Fire is a vigilante movie that casts retribution in world-historic terms.

It’s also a singular work of cinema.

Tony Scott’s movies are often held up as the poster children for our fallen art—the hyperkinetic, the MTV-derived, Ritalin-fueled infotainment with Average Shot Lengths (ASLs) so trigger-happy as to foreclose on any possibility of responsible adult storytelling. (One representative critical bromide aimed at Scott from The Onion’s evaluation of Déjà Vu: “Rarely have Bruckheimer and Scott been so upfront about insulting people’s intelligence.”) And yet Scott is also an unheralded practitioner of such long-out-of-favor screen grammar as the slow fade and the lap dissolve—an improbable link to the utopia of such works as Sunrise and Lonesome. Man on Fire also incorporates unexplained flash-forwards and highly abstracted bursts of ultra-saturated color.

Laying out Scott’s devices one-by-one makes Man on Fire sound like an overzealous film school exercise, one that crams together unmotivated technique to demonstrate a student’s multi-faceted skill. The effect of Man on Fire is quite different. There is one sequence in which Washington sits in a room and contemplates suicide. Dramatically and spatially, it’s a simple set-up, but the cutting fragments it in wholly unexplainable ways. From one shot to another, we’re outside of chronology and outside of space; at moments, we cannot quite say whether one scene has slipped into and displaced another, or whether any physical integrity has been maintained at all. The material world has become voluptuously fragile. If we come away from Man on Fire with the question, “Where am I?,” it is not out of a disgruntled desire for conventional continuity, but a proactive embrace of dislocation.

Parallel Tracks

Is it any coincidence that the first person I knew who recommended Unstoppable, Scott’s unintended swan song, was a projectionist and model train hobbyist? The fundamental analogy between railroad track and film strip has been reiterated often in recent years, not least in the reactions to James Benning’s extraordinary RR and Lynne Kirby’s book-length study Parallel Tracks. Partisans of rail and reel are, after all, often one and the same.

While not nearly as manic as Scott’s underrated satire Domino (a pre-fab, wannabe punk touchstone whose genuine marginality, especially among actual punks, almost accords it such a laurel), Unstoppable is still a mighty abstract action picture, one where color, speed, and mass are expressive tools and the thing being expressed. It’s one hell of a film for train-watchers, especially since Scott and cinematographer Ben Seresin photograph it in an ultra-saturated, ultra-grainy texturalist fashion. (Scott’s late films all originated on 35mm, with editing and color-correction performed through the now-standard Digital Intermediate process. Unlike many of their contemporaries, however, Scott’s films burnish their film aesthetic with an almost comical devotion. The pronounced grain is just another industrial accoutrement on a macho chassis.)

Some advocates of Unstoppable, like Ignatiy Vishnevetsky and Mark Peranson, have bolstered its working-class credentials—a course I find both appealing and somewhat frustrating. Politically-speaking, it’s a blinkered, contrafactual film, where the grizzled freight veteran has survived three decades without a contract and the next-generation college boy represents a union wave. Corporate profit motive is pitched as a foe of public safety, but Hooter’s is advanced as a symbol of upward mobility.

And yet, there’s a sense in which the plot mechanics of Unstoppable are uncommonly sophisticated. The suspense at the heart of the movie issues not from an omnipotent megalomaniac (like, say, Tom Hardy in The Dark Knight Rises or Dennis Hopper in Speed and a hundred other descendants of Dr. Mabuse) but from everyday workplace carelessness. Without a media-savvy villain to pump up the action, we’re left with an unthinking, irrational, and wholly mechanical source of terror. No less than Lars von Trier’s The Boss Of It All (with its randomly selected camera angles), Unstoppable is a product of this very machine, replete with unmotivated camera pans and infinite set-ups. (Scott, somewhat ingeniously, justifies his endless helicopter coverage by incorporating the camera crew into the diegesis, with Fox News always hovering nearby and providing instant replay. Talk about corporate synergy.) Stephanie Zacharek, a long-time Scott skeptic, was quite correct when judging Unstoppable “a thing of majesty and menace … one gleaming machine paying tribute to another.”

As tributes go, Scott couldn’t ask for one more concentrated and beautiful than Unstoppable.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Unstoppable in a 35mm print at Cinema Borealis on Sunday, September 9 at 7:00 and 9:15pm. Please see our calendar for more information. Special thanks to Brian Block.