What do they call this place we are going to?

What do they call this place we are going to?

Paradise.

No, I mean, other people.

Oh, they call it Brooklyn.

What to do with a picture like Give Us This Day?

For one thing, it stands up very well as a domestic drama, a successor in certain ways to King Vidor’s The Crowd. It’s about how the everyday luxuries that constitute the fabric of American culture are not, contra magazine spreads and stump speeches, simply the logical reward of hard work and individual initiative. Give Us This Day shows, in scene after painstaking scene, how a family with the best of intentions may well never achieve its dream. That this obvious fact of sociology nevertheless sounds radical and unexpected in entertainment terms makes a film like Give Us This Day quite bracing, especially today. Indeed, to watch Give Us This Day now invites a certain wistful nostalgia for a moment when a family headed by a sporadically-employed immigrant bricklayer could even contemplate owning a home, an unspeakable ambition for a generation’s worth of college graduates and advanced degree holders these days.

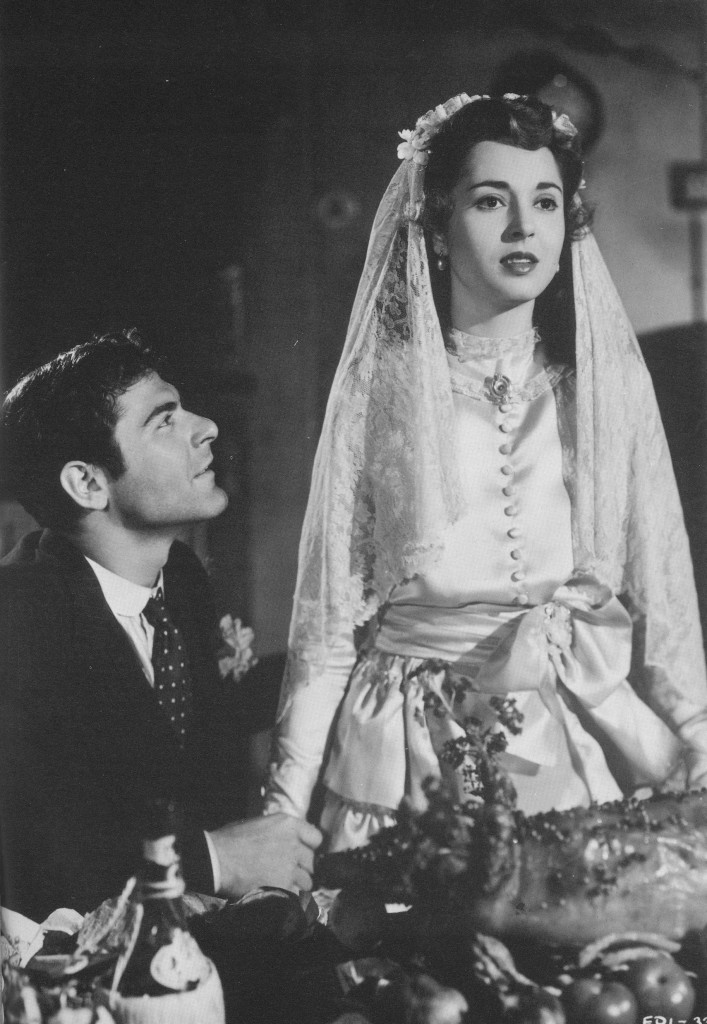

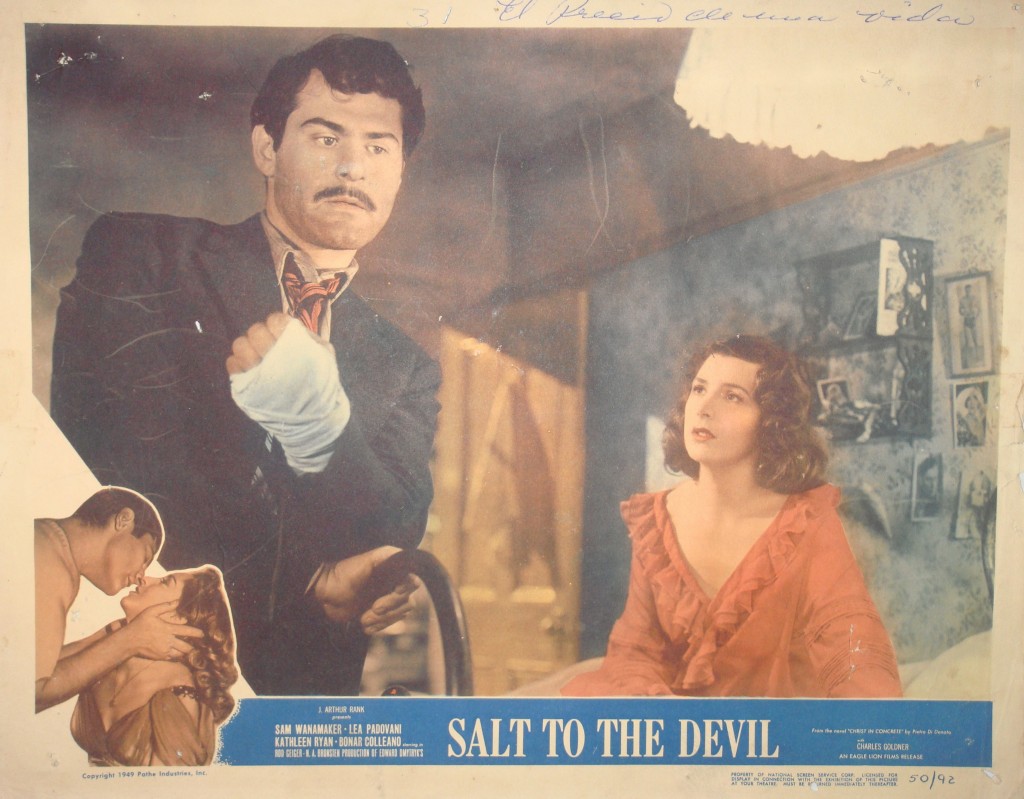

But Give Us This Day is notable for far more than its rarely-fashionable grimness. Like Salt of the Earth, its more storied successor, Give Us This Day is a movie made by blacklisted talent exiled from Hollywood and unusually committed to feeling out what a socially-implicated narrative feature might look and sound like. Inarguably, the answer offered by Give Us This Day is curiously circumspect: aside from an errant ‘CP’ scrawled innocently on a beam in the background of an early scene, there’s next to no acknowledgement of the radical political ideas that halted the careers of actor Sam Wanamaker, writer Ben Barzman, and director Edward Dmytryk. Though such issues as workplace safety and incentive structures that pit workers against each other form important plot points, the possibility of unionization is hardly broached. A ‘union meeting’ is cited once—as the half-assed alibi that Wanamaker supplies when visiting his mistress (Kathleen Ryan).

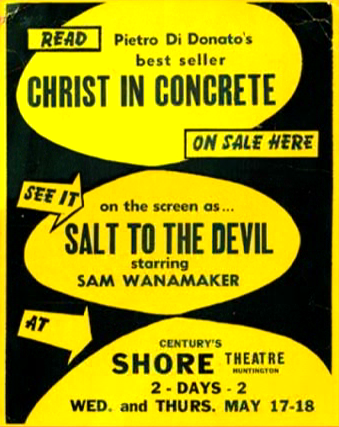

In short, this is a film that diagnoses a social ill but prescribes nothing but human decency—certainly not Communism, or even a slightly more socialized public sphere. Nevertheless, Give Us This Day was sufficiently ‘controversial’ to merit protests and pressure from the American Legion—effectively destroying any semblance of a release. It screened in New York for two weeks and took six months to reach Los Angeles—and even then, under a new title, Salt to the Devil. Distributor Eagle-Lion’s promotional material for 1949 doesn’t even acknowledge the film’s existence. It’s less reputable than Red Stallion in the Rockies and four promised “Red Ryder” Cinecolor westerns.

The project began as neither Give Us This Day nor Salt to the Devil, but Christ in Concrete, a proposed adaptation of bricklayer Pietro di Donato’s experimental proletarian novel of 1939. A surprising Book of the Month Club selection, Christ in Concrete was destined to attract Hollywood attention. Paramount contemplated making it in 1945 and hiring di Donato as a staff writer. Di Donato took a meeting with Frank Capra and rejected the possibility of a collaborative adaptation. (“You capitalist pig, there’s no way I’m going to let you touch this beauty” he reportedly said.)

The project began as neither Give Us This Day nor Salt to the Devil, but Christ in Concrete, a proposed adaptation of bricklayer Pietro di Donato’s experimental proletarian novel of 1939. A surprising Book of the Month Club selection, Christ in Concrete was destined to attract Hollywood attention. Paramount contemplated making it in 1945 and hiring di Donato as a staff writer. Di Donato took a meeting with Frank Capra and rejected the possibility of a collaborative adaptation. (“You capitalist pig, there’s no way I’m going to let you touch this beauty” he reportedly said.)

Di Donato discovered a sympathetic producer in Rod Geiger, the American GI who bluffed his way into ‘producing’ Roberto Rossellini’s Open City. Geiger contracted with Di Donato to translate and subtitle Open City for American distribution through Arthur Mayer and Joseph Burstyn, who promoted it quite successfully as a lascivious sm piece. The profits, which were unprecedented for a foreign film in the US, allowed Geiger to meet his obligations in bankrolling Paisan and bring Rossellini to America to investigate his next picture—Christ in Concrete. (Rossellini had read an Italian translation of the novel, which he liked sufficiently to recommend di Donato for the subtitling job.)

Why Rossellini dropped out remains unclear. (Luchino Visconti’s purported involvement is another tantalizing what-if.) In any case, di Donato’s viewing of Crossfire prompted the author to request that picture’s director, Edward Dmytryk , helm the movie version of Concrete.

The decision to hire Dmytryk was consequential. A recent hostile witness before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee, Dmytryk could not work on any studio picture. Christ in Concrete was shot entirely in Denham, England but for a few second-unit shots of New York City. It was the British censors who insisted on the title change—any mention of Christ in a title was deemed sacrilegious.

Despite the temerity that earned Dmytryk a spot among the Hollywood Ten, the director was not an especially political character. As Norma Barzman would recall, “Eddie joined the party, but never read anything, never understood anything, never really should have been near the Communist Party or anything political because he didn’t understand it.” After the abortive release of Give Us This Day and the jail time he would serve in contempt of Congress, Dmytryk recanted his hostile HUAC testimony and named names.

Despite the temerity that earned Dmytryk a spot among the Hollywood Ten, the director was not an especially political character. As Norma Barzman would recall, “Eddie joined the party, but never read anything, never understood anything, never really should have been near the Communist Party or anything political because he didn’t understand it.” After the abortive release of Give Us This Day and the jail time he would serve in contempt of Congress, Dmytryk recanted his hostile HUAC testimony and named names.

The standard rap on Give Us This Day (especially from David Kalat, who produced this exhaustive DVD edition, released through his label, AllDay Entertainment, in 2003) is that Dmytryk’s status as a political pariah, unwanted on the right and on the left, damned the movie to undeserved oblivion. One can certainly understand why the left would want nothing to do with Dmytryk, who continued to position himself as an anti-Communist long after HUAC had closed up shop. Complaining to the Los Angeles Times in 1966 that it was a mistake to ‘laugh off’ the Party, Dmytryk warned that subversive elements were capable of infiltrating decent liberal causes like civil rights marches and peace demonstrations. In recalling his friendly testimony, the ‘extremely liberal’ Dmytryk displayed a damning lack of empathy. “They’re responsible,” Dmytryk offered of fellow black-listed talent like Barzman and Wanamaker. “It is wonderful to be a martyr in a just cause but stupid to be a martyr in an unjust one …. I’d do it all over again.” He boasted, too, that ‘our kind of democracy’ had weathered the Red Scare more or less unscathed.

Easy for him to say. Dmytryk’s career, post-recantation, saw steady Hollywood employment. In contrast, Barzman, who was never even paid for Give Us This Day, had to write scripts pseudonymously in exile. Wanamaker devoted his career to theater and was largely responsible for the renovation of Shakespeare’s Globe. (A Chicagoan, Wanamaker is commemorated with an honorary street sign at Randolph and State.)

Dmytryk’s uncontemplated and ugly sense of political entitlement should never go unmentioned, but other equally loathsome players in the HUAC drama have seen some rehabilitation. The left doesn’t much like Elia Kazan either (and with good reason), but that hasn’t suppressed his work. Indeed, the notion that Give Us This Day has been ‘buried’ by the left because of Dmytryk’s friendly testimony is self-evidently absurd and, come to think of it, resembles the intellectually worthless crazy-mirror contortions of a Kazan scenario: the Communists are the all-powerful state auxiliaries and the informers the lone individuals who risk everything by valiantly collaborating. (The reasons for Give Us This Day’s invisibility are more prosaic: its one-off production company, Plantagenet, was dissolved and no prints were kept; rights reverted to di Donato, but he could do little with them without a copy of the film. After discovering that a copyright registration print had been retained by the Library of Congress, the film was still kept out of circulation as di Donato and his agent planned a never-filmed remake with Robert DeNiro.)

No political rebel, Dmytryk’s career is neglected because it’s frequently so aesthetically impoverished. And yet it’s difficult to read over the list of post-Give Us This Day Dmytryk projects and fix upon any worth remembering or revisiting. Who else could blow so much money on Raintree County—along with Ben-Hur, the only other feature shot in M-G-M’s ultra-widescreen Camera 65—and deliver a picture so witless and dull that terming it a ‘folly’ would be a generous stretch? (There’s not enough passion or delirium for that.) Dmytryk’s The Carpetbaggers was a major blockbuster in 1964 and barely remembered today, even among those fond of skewering out-of-touch sixties studio efforts. Even his Oscar-nominated direction of Crossfire is a dull slog that never manages to translate the rote anti-anti-Semitism of the material into something emotionally or formally involving. There’s political passion here, but it’s muted—made to look small and tentative, even when aspiring to outspokenness. It’s telling that Dmytryk isn’t included anywhere in Andrew Sarris’s seminal 1968 auteurist survey The American Cinema; no one takes him seriously enough to qualify for ‘Strained Seriousness’ or holds him in high enough regard for a deflating ‘Less Than Meets the Eye.’

No political rebel, Dmytryk’s career is neglected because it’s frequently so aesthetically impoverished. And yet it’s difficult to read over the list of post-Give Us This Day Dmytryk projects and fix upon any worth remembering or revisiting. Who else could blow so much money on Raintree County—along with Ben-Hur, the only other feature shot in M-G-M’s ultra-widescreen Camera 65—and deliver a picture so witless and dull that terming it a ‘folly’ would be a generous stretch? (There’s not enough passion or delirium for that.) Dmytryk’s The Carpetbaggers was a major blockbuster in 1964 and barely remembered today, even among those fond of skewering out-of-touch sixties studio efforts. Even his Oscar-nominated direction of Crossfire is a dull slog that never manages to translate the rote anti-anti-Semitism of the material into something emotionally or formally involving. There’s political passion here, but it’s muted—made to look small and tentative, even when aspiring to outspokenness. It’s telling that Dmytryk isn’t included anywhere in Andrew Sarris’s seminal 1968 auteurist survey The American Cinema; no one takes him seriously enough to qualify for ‘Strained Seriousness’ or holds him in high enough regard for a deflating ‘Less Than Meets the Eye.’

And yet Give Us This Day emerges as an emotionally complex—and well-directed!—film. A large part of the effect comes from the knowledge that the picture was shot almost entirely in England. The integration of rear projection footage of New York is exemplary and the locations are frequently convincing. (The British accents of Wanamaker’s children are the most serious fissure.) Like Chaplin’s A King in New York, Give Us This Day is moving precisely because it tries so desperately to recreate and critique the nation the filmmakers know only as a memory and a tarnished ideal. If anything, Dmytryk’s subsequent actions make its clarity even rarer—a country twice lost.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Give Us This Day in a 35mm print from the Library of Congress on March 7 at the Portage Theater as part of its Classic Film Series. Please see our current calendar for more information. Special thanks to Rob Stone and Lynanne Schweighofer. The research for this piece draws heavily from the materials assembled by David Kalat for his AllDay Entertainment DVD edition of Christ in Concrete.