In 1939, sociologist Margaret Farrand Thorp called the movies “the vampire art” and it’s not difficult to see where she’s coming from. With Hollywood at the height of its powers (economic, cultural, political), everything bowed before the movies. They cannibalized and superseded competing media with finesse. Screen rights to big novels were snatched up before publication. (And the movie version prompted new tie-ups, like Photoplay Editions of the book adorned with production stills.) Unexpected successes were dealt with, too. Studios raced to buy them up, even if screen potential was dubious or non-existent. (So what if the option was never exercised? Always better to stay ahead of the competition, either way.) Thorp’s most staggering example of this mentality is Dale Carnegie’s runaway best-selling self-helper How to Win Friends and Influence People, optioned by an unnamed studio.

As far as I can tell, the cinematic How to Win Friends never got past (or got to?) the development stage. But one equally improbable contemporary made it to the screen, albeit with severe alterations applied both before and after the cameras rolled.

As far as I can tell, the cinematic How to Win Friends never got past (or got to?) the development stage. But one equally improbable contemporary made it to the screen, albeit with severe alterations applied both before and after the cameras rolled.

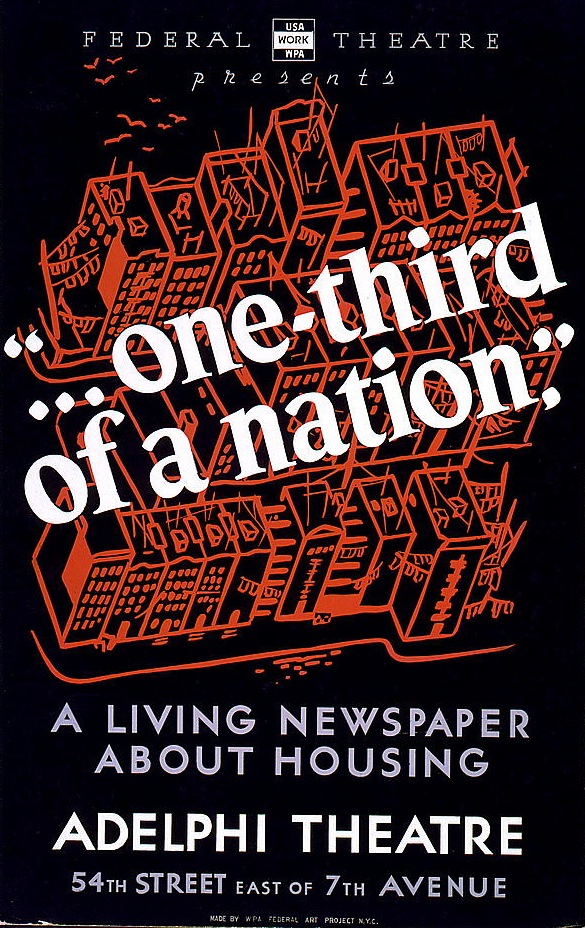

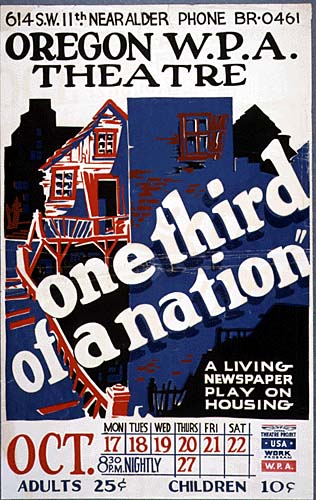

…one third of a nation… was not the first Living Newspaper produced by the Federal Theater Project, but it was unquestionably the most successful of the Works Progress Administration-sponsored plays. Opening on 17 January 1938 at New York’s Adelphi Theater, it ran for nine months and was seen by well over 200,000 people. Local versions played ten other cities with comparable success. In short, …one third of a nation… was, on paper, a dream of a pre-sold property, instantly recognizable to moviegoers all over country. (It helped, too, that the play made headlines even in cities where it wasn’t performed; early in the New York run, a charge of Communist influence was lobbed by a trio of Democratic Senators whose floor speeches were quoted verbatim in the script.)

The premise of the Living Newspaper was simple: marry politically-committed theater and ultra-current broadsheet, with other popular entertainment—radio, newsreel, public lecture—thrown in where possible. The plays were kaleidoscopic, favoring black-out sketches and abrupt shifts in time, space, and scenery over more traditional dramatic virtues. Joseph Manning described a typical scene from one of the earlier Newspapers, Highlights of 1935, in the pages of New Theatre:

The curtain opens on a bunch of scared young girls and reveals the lengths to which small New Jersey towns will go to keep America safe for the exploited open shop. The episode ends with another piece of testimony acted out. One of the young ladies finds her pay is short. She goes to the office girl. She’s right. Her pay is short. But wait— that’s the book for the NRA code inspector. According to the book she gets paid by, the miserable wage she got is all she had coming. No climax. The critics call it anticlimax. The boys of the fourth estate who edit the Living Newspaper are just telling a story for what it is worth. The scene may lack the customary punch expected at the end of a dramatic sketch. Anyone viewing it, though, should be able to see why labor needs some legal protection.

There wasn’t a story in …one third of a nation…, but a subject: the abject state of housing in Depression-era America. This was illustrated with a condensed history of the New York real estate market from colonial times to the present day. Stump speeches, conference negotiations, human dramas, and two burnings of the four-story tenement set were recreated during each performance. Slum statistics were recited over loudspeaker.

Contemporary reviews credited playwright Arthur Arent as ‘managing editor’ and cited 26 researchers who drew the incidents from 20,000 pages of relevant material. Over 80 actors were employed, making …one third of a nation… undoubtedly the most elaborate bit of stagecraft ever deployed in the name of lefty American agitprop. The chief purpose of the production was, after all, keeping theater workers gainfully employed with maximum bang for federal buck.

Actually, … one third of a nation … was a profitable play, even though top admission was $1.10 (compared to $2 or $3 for Broadway fare) and many tickets were sold on a group basis at a heavy discount. It was a blockbuster show, playing to capacity houses for weeks. Eleanor Roosevelt took in a New York performance and the Washington preview was attended by dignitaries from Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black to Soviet ambassador Oleg Troyanovsky. It attracted strong reviews, too, even from the Wall Street Journal.

Actually, … one third of a nation … was a profitable play, even though top admission was $1.10 (compared to $2 or $3 for Broadway fare) and many tickets were sold on a group basis at a heavy discount. It was a blockbuster show, playing to capacity houses for weeks. Eleanor Roosevelt took in a New York performance and the Washington preview was attended by dignitaries from Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black to Soviet ambassador Oleg Troyanovsky. It attracted strong reviews, too, even from the Wall Street Journal.

The film rights were purchased in June 1938 and the shooting begun in August while …one third of a nation… was still on offer at the Adelphi. The measly $5,000 offered for the rights went to Federal Theater, rather than Arent, as the play was conceived and understood as public property. (The money was funneled to the WPA’s Federal Writer’s Committee.) The deal would see an independent feature overseen by Broadway producer Harold Orlob, to be filmed on a very modest budget in Astoria’s Eastern Service Studios Inc. Sylvia Sidney was announced to star and this made sense; between Street Scene, Fury, Dead End, and You Only Live Once, she had established herself as the go-to actress for progressive, urban projects. Her new husband, Luther Adler (brother of Stella), was also announced, but soon replaced by Group Theatre loan-out Leif Erikson.

Adapting …one third of a nation… to the screen was both a natural proposition and an inevitable dilution. In the credit column, …one third of a nation… was already a kind of proto-cinema: the play’s hair-trigger mix of facts, dramatic incident, and spectacle had already been likened by drama critic Stirling Brown to Hearst’s March of Time newsreels. Some Living Newspapers productions even incorporated film clips into the battery of didactic evidence. (And no wonder: Arent’s first paying gig was as film critic for Exhibitor’s Daily Review.)

But this dynamism also worked against screen translation. Like its contemporary, Hellzapoppin’, …one third of a nation… was a kind of epic, unruly theater that resisted the finished form of film. There was too much information, too much history, too many tangents—nothing like this could resemble conventional commercial cinema. The title and the basic thrust were maintained but little else: the panoramic account of housing rights was condensed to one story, and one that allowed for both a tender love angle between Sidney and Erikson and some scenes set in the latter’s tony landlord surroundings, which were alien to the play. There was no loudmouthed loudspeaker recitation in this movie.

Calling the film version of …one third of a nation… a travesty of the play misses the point. Though it was formally quite different, the play itself was not a fixed entity. The New York production was continually updated, as explained by a New York Times account early in the play’s run:

[O]ther changes in detail are being made in the text to keep the play abreast of day-to-day developments in the local and national housing situation. The most frequent changes are made in the speeches of the character of Mayor LaGuardia, because of developments in New York housing news. The actor who plays Mayor LaGuardia therefore does not know when he arrives at the theater what his lines are going to be for the evening.

The stage versions mounted elsewhere made further changes to address local concerns. The Washington iteration had an added scene that recounted details of slums in the District; the Philadelphia rendition changed the tenement fire to a building collapse to mirror recent headlines. The film isn’t the play, but which play? In some sense, the film is just another local edition, told in the terms that the community could understand (in this case, those terms derive from showbiz clichés rather than journalism, per se).

The stage versions mounted elsewhere made further changes to address local concerns. The Washington iteration had an added scene that recounted details of slums in the District; the Philadelphia rendition changed the tenement fire to a building collapse to mirror recent headlines. The film isn’t the play, but which play? In some sense, the film is just another local edition, told in the terms that the community could understand (in this case, those terms derive from showbiz clichés rather than journalism, per se).

The film version of …one third of a nation… faced more basic problems. Though it was distributed by Paramount, it was wholly financed on an independent basis, largely by Atlas Corp. investment magnate Floyd Odlum. One is not surprised, then, that the play’s impassioned dialogue about the Senate debate surrounding the Wagner-Steagall provision (“Balance the budget? What with? Human lives? Misery? Disease? What was the appropriation for the army and navy for the last four years?”) was missing in the film. Even clips of Roosevelt’s second inaugural speech, from which the title derives, were cut after being declared New Deal propaganda by the financiers. That a socially-concerned film was made at all under such conditions is astonishing.

Reshoots were ordered to stave off presumed censorship trouble and the release date pushed from 1938 to 1939. (This delay was not advantageous, critically-speaking: perhaps …one third of a nation… would have a better reputation today if it had been released in 1938, one of the worst years in Hollywood history, as opposed to being just another GWTW also-ran in the goldleaf glow of 1939.) Industry reaction was, naturally, hostile. The East Coast Threat had receded when Paramount pulled out of Astoria production in 1931 and the last thing Hollywood wanted was a replay of the rivalry. (William K. Howard’s concurrently-produced Back Door to Heaven added fuel to the Astoria headache.) The Los Angeles Times noted snidely that “…‘One Third of a Nation’ isn’t so far removed from Hollywood ideas as the local pundits expected. Its approach to the subject of housing greatly resembles the realistic Warner films to which we’re accustomed, and it is inferior to many of them.”

Reshoots were ordered to stave off presumed censorship trouble and the release date pushed from 1938 to 1939. (This delay was not advantageous, critically-speaking: perhaps …one third of a nation… would have a better reputation today if it had been released in 1938, one of the worst years in Hollywood history, as opposed to being just another GWTW also-ran in the goldleaf glow of 1939.) Industry reaction was, naturally, hostile. The East Coast Threat had receded when Paramount pulled out of Astoria production in 1931 and the last thing Hollywood wanted was a replay of the rivalry. (William K. Howard’s concurrently-produced Back Door to Heaven added fuel to the Astoria headache.) The Los Angeles Times noted snidely that “…‘One Third of a Nation’ isn’t so far removed from Hollywood ideas as the local pundits expected. Its approach to the subject of housing greatly resembles the realistic Warner films to which we’re accustomed, and it is inferior to many of them.”

Critical reaction was otherwise positive. The neutered …one third of a nation… even received a rave notice in The New Masses, which congratulated the company “for the rare feat of making a picture in which the hero is a house.”

Unfortunately, …one third of a nation… has been mighty hard to see for many years. Because Paramount’s terms were for short-term lease, this title was not included in the package of early talkies sold wholesale to MCA. Eventually, it fell into the public domain and its social context faded from memory, an orphan commercially and politically. (Like its cousins Street Scene and After Tomorrow, it leads directly to the sentimental urban melting pot of Sesame Street.) Luckily, the Library of Congress has seen fit to preserve this curious version of an extraordinarily important piece of American theatrical history.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening …one third of a nation… in a 35mm preservation print as part of its Classic Film Series on Wednesday, January 25 at the Portage Theater. Special thanks to Rob Stone and Lynanne Schweighofer of the Library of Congress. Please see our current schedule for more information.

FURTHER READING

Arent, Arthur, et al. Federal Theater Plays. New York: Random House, 1938.

Browder, Laura. Rousing the Nation: Radical Culture in Depression America. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998.

Flanagan, Hallie. Arena: The History of the Federal Theater. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940.

Kline, Herbert, ed. New Theatre and Film-1934 to 1937: An Anthology. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985.

Quinn, Susan. Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times. New York: Walker and Company, 2008.

Federal Theater Project Web Guide at the Library of Congress.