There are some who insist that the studios must surrender—or make otherwise available—the entirety of their libraries. Whether by streaming or manufactured-on-demand discs, there are completists who want every Tim Holt western, the whole Mexican Spitfire series, all the Harman-Ising cartoons, a box set of Fox’s first season of Cinemascope releases, and anything that could be half-seriously classified film noir. Everyone has predilections and bless those with the patience and enthusiasm to husk through what even partisans must admit is a lot of chafe. They make the discoveries for the rest of us.

There are some who insist that the studios must surrender—or make otherwise available—the entirety of their libraries. Whether by streaming or manufactured-on-demand discs, there are completists who want every Tim Holt western, the whole Mexican Spitfire series, all the Harman-Ising cartoons, a box set of Fox’s first season of Cinemascope releases, and anything that could be half-seriously classified film noir. Everyone has predilections and bless those with the patience and enthusiasm to husk through what even partisans must admit is a lot of chafe. They make the discoveries for the rest of us.

Hardcore auteurists function in the same way, talking up an unseen Joseph M. Newman or Allan Dwan as if every 64-minute excavation is a revelation. Mention of an extraordinary tracking shot in an otherwise undistinguished programmer or a faint echo of a situation from an earlier film is usually enough. Strictly speaking, this is all true and valid, but one cannot help but feel that the bar for revelation is sometimes set awfully low.

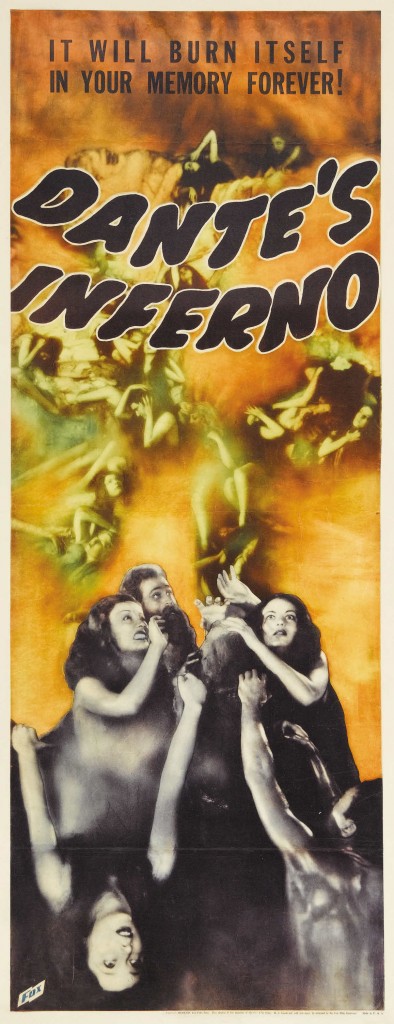

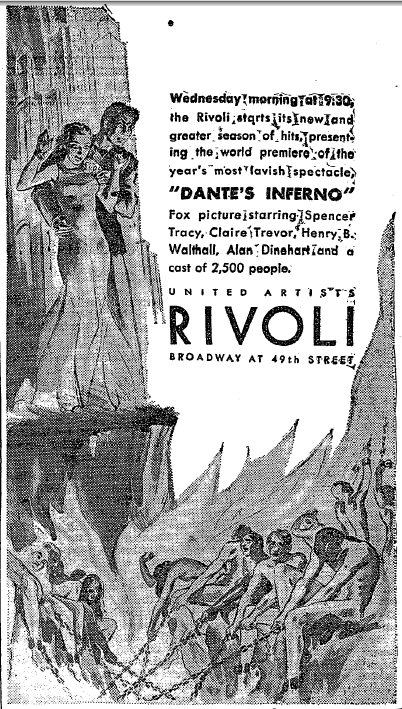

When one comes upon something like Dante’s Inferno, also more-or-less forgotten and not much invoked in screen histories, one scrambles for a critical vocabulary to describe it. It has the emotional, dramatic, social, and technical scope that rightly constitutes a classic. It is unmistakably a major production, not simply in terms of expenditure but as an exemplar of a cultural moment.

When one comes upon something like Dante’s Inferno, also more-or-less forgotten and not much invoked in screen histories, one scrambles for a critical vocabulary to describe it. It has the emotional, dramatic, social, and technical scope that rightly constitutes a classic. It is unmistakably a major production, not simply in terms of expenditure but as an exemplar of a cultural moment.

Though one can assign causes proximate (lack of a circulating 35mm print) and speculative (ample nudity then, a gratuitous blackface bit now) to Dante’s Inferno’s obscurity, the highest barrier is likely the undisguised fact that the show is very 1935. In a non-trivial way, Dante’s Inferno ties together and completes many of the movie threads that had criss-crossed the early talkies: ambition arising from economic desperation, a sympathetic and admiring view of a tycoon, a sub-entertainment-industry setting, a wink at labor unrest, a dollop of ripped-from-the-headlines exploitation, generational conflict that puts modernity itself on trial, and, above all, a spiritual quality that subtly but sincerely slides from snide to devout. This is a ‘preachment yarn’ in the most thorough sense of that phrase.

The very great Warren William-Roy Del Ruth Mind Reader of two years earlier shares and synthesizes much of the same stuff, but nothing competes with Dante’s Inferno on matters of scale. What other movie, not quite satisfied with a ten-minute tour of hell, would shoehorn in a restaging of the SS Morro Castle tragedy in the last reel?

From the moment that the set-up comes into focus—Spencer Tracy will partner up with antiquarian preacher-concessionaire Henry B. Walthall and take over the fairground with increasingly elaborate iterations of Dante’s Cabinet of Infernal Curiosities—one senses a moral landscape with almost topographic weight and solidity. It’s a religious-capitalist parable told in totally pop terms beyond what even Aimee McPherson could have dreamed.

No ramshackle carnival stand this, Dante’s Inferno is also clearly a production whose makers had something to prove, a climatic testament. In planning for over a year under the old Fox Film Corporation regime, but released in the first wave of post-merger 20th Century-Fox product, it feels like a booming testament to a studio craft culture under threat from external (divine?) forces barely understood by the rank and file.

No ramshackle carnival stand this, Dante’s Inferno is also clearly a production whose makers had something to prove, a climatic testament. In planning for over a year under the old Fox Film Corporation regime, but released in the first wave of post-merger 20th Century-Fox product, it feels like a booming testament to a studio craft culture under threat from external (divine?) forces barely understood by the rank and file.

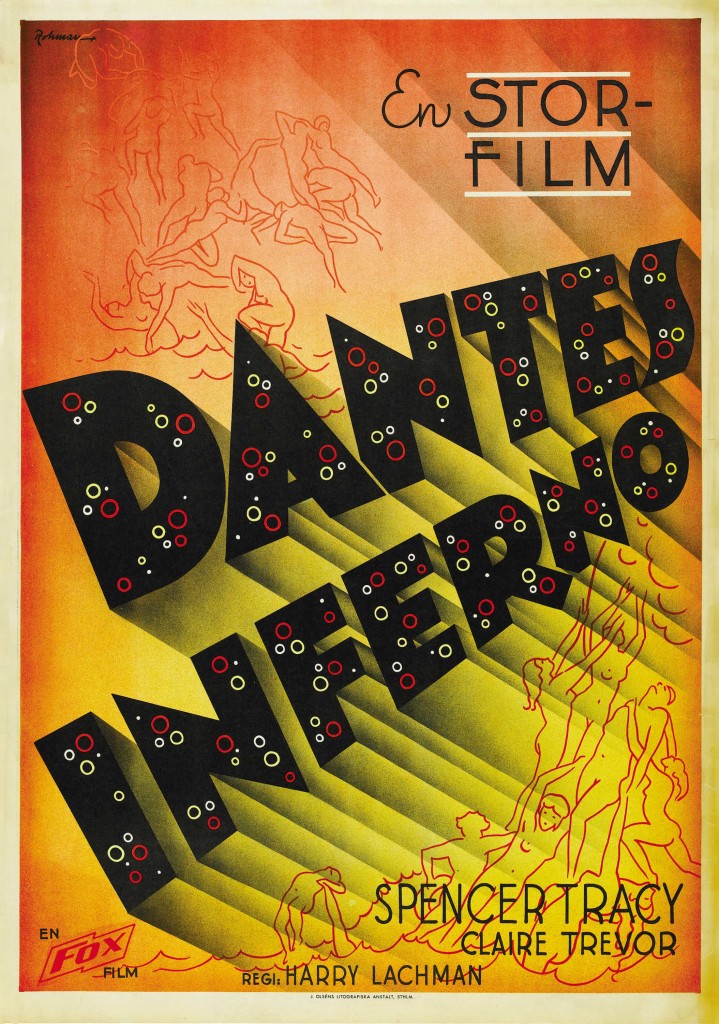

It was the last picture that Spencer Tracy made under his Fox contract before moving over to MGM and, on the whole, history has judged the sexy, excitable zip of his performances in Dante’s Inferno, Quick Millions, Me and My Gal, and the Columbia loan-out Man’s Castle much more kindly and avidly than the sanctimonious respectability that followed. Screenwriter Philip Klein, scenarist for archetypically Fox product like Street Angel and Four Sons, died two months before its release. It was also a milestone credit for co-writer Robert M. Yost, a longtime Fox loyalist and lately head of the scenario department, who was disappeared to a Paramount B unit in the aftermath of the merger.

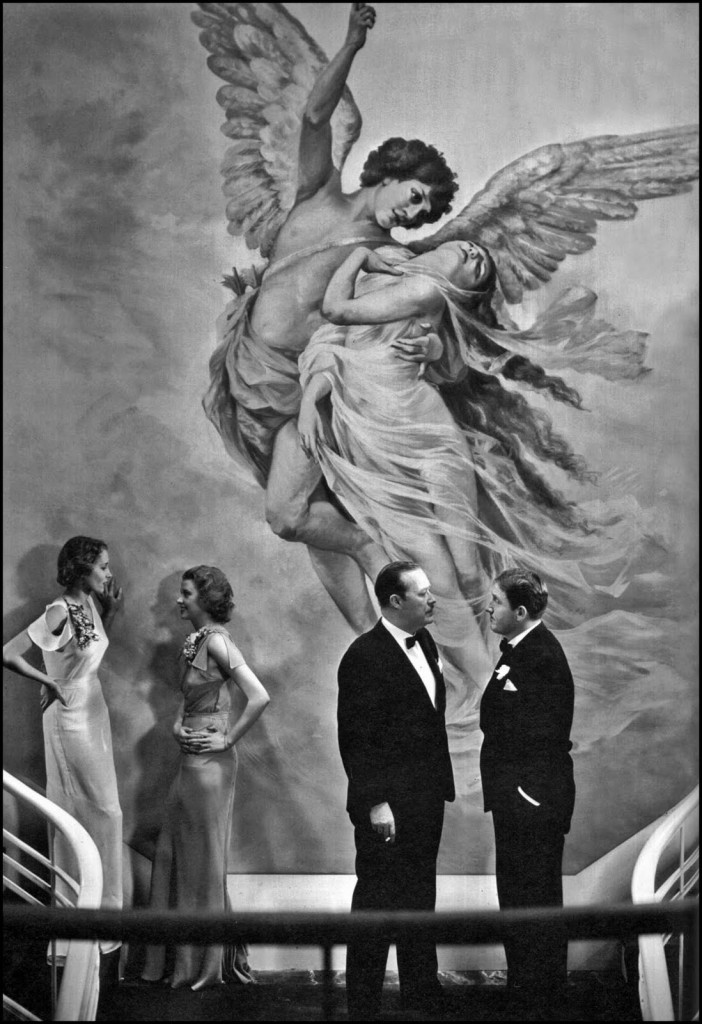

Dante’s Inferno also proved director Harry Lachman’s only real crack at a major production, a fact ameliorated by the varied and fascinating dimensions that his career took on anyway. Born in LaSalle, Illinois, Lachman worked as a commercial illustrator and later gained notoriety in Paris, where his post-Impressionist views of boulevards and urban skylines received almost instantaneous recognition and quick sales. (Some of his work remains in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago and elsewhere.) Slowly, Lachman found his way into the movies. He made an abstract short that was screened at the Film Society in London. He also became an assistant to Hollywood director Rex Ingram, who had the clout to shoot his films on location in Europe. Lachman worked as a production manager for Ingram’s The Magician, which itself contains an elaborate sequence set in hell that obviously presages Dante’s Inferno.

After the talkies took over, Lachman found himself supervising French-language versions of Hollywood properties and directing features for Fox’s British office. When he eventually returned to America, he was given bread-and-butter Fox assignments (e.g., Janet Gaynor’s Paddy the Next Best Thing and Shirley Temple’s Baby Take a Bow). He was loaned out to Hal Roach for Our Relations and Columbia for the terrific It Happened in Hollywood but returned to Fox to do more programmers, his last being the disarmingly sympathetic ape man mystery, Dr. Renault’s Secret.

Only a fool would try to find a thematic link to unite Lachman’s journeyman output (including five Charlie Chan entries, a major impediment to his auteurist revival), but there’s no denying either that Lachman possessed a fleet touch that often evinced a real sweetness. When watching a Lachman picture, you have the sense that so cultivated a personality could have easily found something better to do with his time, but happily toiled in Hollywood anyway. Indeed, after Dr. Renault’s Secret, he devoted his time to collecting and dealing fine art, operating a shop profiled some years later in a Pete Smith Specialty short.

(Just about the only personality to emerge from Inferno in a significantly better position was 16-year-old Rita Cansino, later Hayworth, who was much noticed in a bit dancing part and started getting plum assignments at Fox almost immediately. She went from being a dancer at Hollywood’s Agua Caliente club to receiving third billing in Charlie Chan in Egypt practically overnight, with the Chan picture actually beating Dante’s Inferno into release by a few weeks.)

As to the studio’s motivations, it seems well enough to say that Fox brass wanted to jump on the post-Code band wagon of literary adaptations that commanded a significant portion of 1934-1935 release schedules. The source material shift from unproduced plays about prostitutes and floozies to classics of world literature was a key demonstration of the industry’s renewed dedication to the family audience, touted as such by Will Hays and educators around the country. If the other studios would put out Anna Karenina, Les Miserables, David Copperfield, Treasure Island, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, so Fox would produce its own Dante’s Inferno, on its own terms.

As to the studio’s motivations, it seems well enough to say that Fox brass wanted to jump on the post-Code band wagon of literary adaptations that commanded a significant portion of 1934-1935 release schedules. The source material shift from unproduced plays about prostitutes and floozies to classics of world literature was a key demonstration of the industry’s renewed dedication to the family audience, touted as such by Will Hays and educators around the country. If the other studios would put out Anna Karenina, Les Miserables, David Copperfield, Treasure Island, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, so Fox would produce its own Dante’s Inferno, on its own terms.

Those terms were not conventional adaptation, but closer to the technique that DeMille had pioneered with The Ten Commandments—interlacing a classic and instantly recognizable story with a self-consciously modern parallel. They’re about the confusions and delusions of the very demographic they’re trying to reach. While all the other studios were treating the classics as timeless blueprints for high class screen entertainment, Dante’s Inferno is wrestling, openly and earnestly, with the task and with the fundamental irreconcilability between past and present. Again, it’s rooted precisely in its time in a way that’s less timorous and more edifying than its contemporaries—a dated film, in the positive sense of that term.

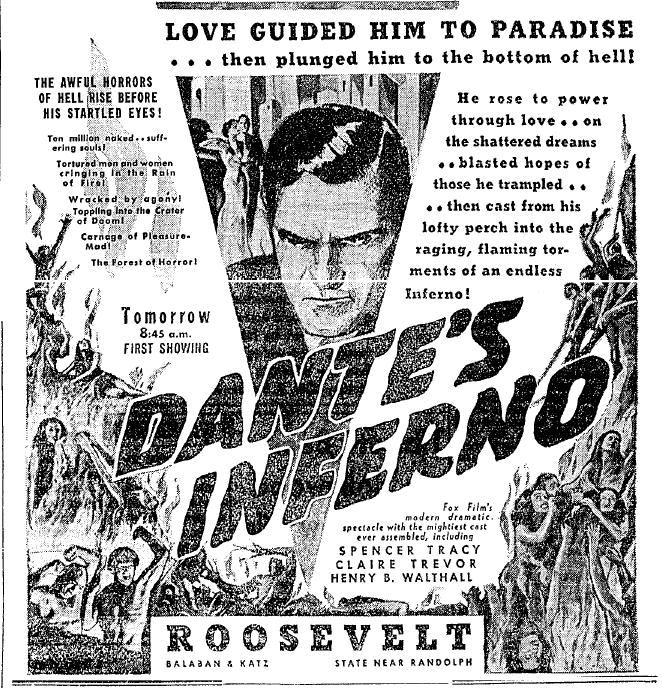

Naturally, though, Fox did not promote Dante’s Inferno on this unique basis, choosing instead to yolk its whole publicity campaign to the brimstone reel. The number of extras, technicians, man hours, and the like grew larger with each article. (The Los Angeles Times claimed that 13,000 appeared on screen, putting it not far short, practically speaking, of the ten million ‘Naked, Suffering Souls’ cited in ads.) Five-thousand technicians worked out the details for thirteen months. A crew spent two weeks in the Sierra Nevadas and returned with life-size plaster casts of towering crags and heinous rock formations. One extra described shooting delayed numerous times when “the camera couldn’t register because hell vapors became too thick.” The ten-minute inferno sequence commanded 300,000 feet of exposed negative, which makes the generally profligate 500,000 feet used for the remaining eighty minutes look rather economical. (The finished feature is a little over 8,000 feet.)

In fairness to Fox, Spencer Tracy’s hatred of the picture and insistence that his name not be used in any ads limited the studio’s options. Still, the focus on this admittedly spectacular sequence has tended to diminish interest in the whole—and those going in expecting a feature-length rendition of the sumptuous production stills will surely be disappointed. If you can look past it, you’ll find a defining masterpiece of ’30s cinema. And your soul might well be saved in the bargain.

The Northwest Chicago Film Society will be screening Dante’s Inferno on Wednesday, July 13 at the Portage Theater in a 16mm print from Criterion Pictures, USA. Please see our current calendar for additional information. Special thanks to Brian Block and Anthony L’Abbate.