Our screenings are held at multiple venues around Chicago. This season you can find us at:

• The Music Box Theatre

3733 N Southport Ave — Directions • Parking

Tickets: $11 – $15

• The Gene Siskel Film Center

164 N State St — Directions • Parking

Tickets: $13

• The Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts (Film Studies Center Screening Room)

915 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637 — Directions • Parking

Tickets: $10

• Constellation

3111 N Western Ave — Directions • Parking

Tickets: $15

Want to attend our screenings but having financial hardships? Contact info@chicagofilmsociety.org

SEASON AT A GLANCE

☆ = Pre-Code Picture Party May 1 – 3

February ▼

Thursday 2/12 at 7:30 PM ………. Music Box

Lady Windermere’s Fan

Tuesday 2/17 at 7:00 PM ……….. Music Box

Written on the Wind

March▼

Sunday 3/1 at 6:00 PM ………. Film Center

Young Mr. Lincoln

Sunday 3/8 at 7:00 PM ……….. Music Box

Battleship Potemkin

Sunday 3/15 at 11:30 AM ……….. Music Box

Selections from the Vinegar Syndrome Film Archive

Wednesday 3/18 at 8:00 PM ………. Constellation

Quick Billy

Sunday 3/29 at 6:00 PM ………. Film Center

Ah Ying

April ▼

Monday 4/6 at 6:30 PM ………. Music Box

Reds

Saturday 4/18 at 11:30 AM ………. Music Box

Real Life

Sunday 4/26 at 6:00 PM ………. Film Center

Henry Fool

May ▼

Friday 5/1 – Sunday 5/3 …….. Logan Center for the Arts

☆ Pre-Code Picture Party ☆

Friday 5/1 at 7:00 PM

☆ Horse Feathers ☆

Friday 5/1 at 9:00 PM

☆ Ladies Must Love ☆

Saturday 5/2 at 3:00 PM

☆ The Letter ☆

Saturday 5/2 at 4:45 PM

☆ The Wiser Sex ☆

Saturday 5/2 at 8:00 PM

☆ Wild Boys of the Road ☆

Sunday 5/3 at 1:00 PM

☆ His Wife’s Lover ☆

Sunday 5/3 at 3:00 PM

☆ Caravan ☆

Sunday 5/3 at 5:30 PM

☆ Anybody’s Woman ☆

Saturday 5/16 at 11:30 AM ………. Music Box

Salomé

Monday 5/25 at 7:00 PM ………. Music Box

Beavis and Butt-Head Do America

Sunday 5/31 at 6:00 PM ………. Film Center

Fly Away Home

☆ Sign up for our newsletter for screening reminders!

☆ Add the schedule to your google calendar!

Thursday, February 12 @ 7:30 PM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets: $12

LADY WINDERMERE’S FAN

Directed by Ernst Lubitsch • 1925

“Playing with words is fascinating to the writer and afterward to the reader, but on the screen it is quite impossible. Would much charm remain to long excerpts from Wilde’s play if the audience had to ponder laboriously over the scintillating sentences on the screen?” And so Ernst Lubitsch justified his temerity (or chutzpah) in mounting a silent version of Lady Windermere’s Fan, but without any of Wilde’s celebrated dialogue, not even in the intertitles. What remains is a visually witty, closely observed, emotionally nuanced rendering of Wilde’s basic plot, as filtered through Lubitsch’s everyday eroticism. Irene Rich stars as Mrs. Erlynne, the long-absent mother of Lady Windermere (May McAvoy), whose return to the London scene coincides with her daughter’s temptation to pursue a dalliance with Lord Darlington (Ronald Colman). Lady Windermere, who believes her mother is dead, begins to wonder why this older woman is intent on infiltrating her social circle. Perhaps Mrs. Erlynne plans to steal Lord Windermere — which might not be entirely inconvenient? Lady Windermere’s Fan was met with near-unanimous praise upon its release, with Lubitsch’s departures from the original text decidedly uncontroversial for moviegoers and their fan magazines. “The plot by Oscar Wilde was not so original,” sniffed Photoplay. “With Wilde’s epigrams it became literature. With Lubitsch’s subtle translation it is delightful.” Preserved by the Museum of Modern Art with support from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation. (KW)

89 min • Warner Bros. • 35mm from the Museum of Modern Art

Live musical accompaniment by David Drazin

Preceded by: “A Musical Mixup” (Les Goodwins, 1928) – 21 min – 35mm from the Chicago Film Society collection

“A Musical Mixup” has been restored by Chicago Film Society in collaboration with UCLA Film and Television Archive and Cineverse with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation

Tuesday, February 17 @ 7:00 PM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets: $11

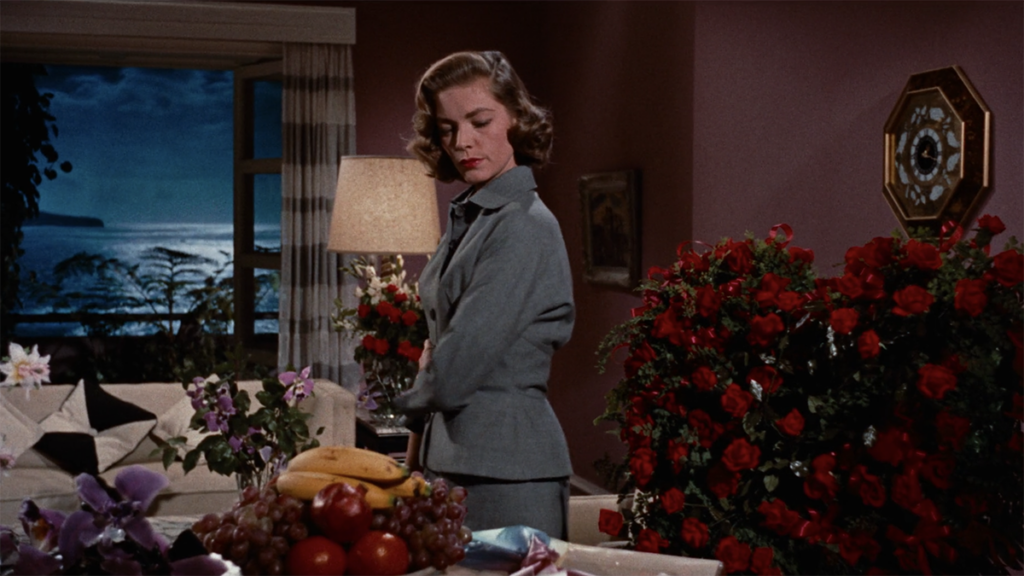

WRITTEN ON THE WIND

Directed by Douglas Sirk • 1956

Perhaps the most anxious and lurid of Sirk’s incredible run of melodramas for Universal-International, Written on the Wind is a soap opera laid in a Texas too extravagant for even Edna Ferber. Everything is outsized but off-center — big, big oil derricks, shotgun aeroplane weddings, saloon brawls, and a hoochie-cooch pagan jazz dance that embarrasses Old Testament fury. Even a child’s bucking bronco becomes a crude-cruel reminder of vanished potency. Robert Stack and Dorothy Malone star as those danged spoiled rich thirtysomething Hadley brats with a Texas-sized deficit of self-awareness and restraint. (Malone won a much-deserved Oscar, in a mind-boggling moment of slumming for Academy voters, for a role described by the Village Voice as a “nymphomaniac, which makes Marilyn Monroe look like Margaret O’Brien.”) Rock Hudson plays longtime Hadley hanger-on Mitch Wayne, born with sense and decency rather than a trust fund. Lauren Bacall plays Stack’s wife, a tragic witness to the unraveling. “It is like the Oktoberfest, where everything is colorful and in movement, and you feel as alone as everyone,” observed Sirk disciple Rainer Werner Fassbinder. “Human emotions have to blossom in the strangest ways in the house Douglas Sirk has built for the Hadleys.” (KW)

99 min • Universal International Pictures • 35mm from Universal

Preceded by: “Hold Me While I’m Naked” (George Kuchar, 1966) – 15 min – 16mm from Anthology Film Archives

On February 16, 2011 we held our first-ever screening. We had about $250 in our bank account and we spent it all to rent Universal’s print of Written on the Wind. We’re celebrating our 15th birthday with a reprise!

Sunday, March 1 @ 6:00 PM

Gene Siskel Film Center / Tickets: $13

YOUNG MR. LINCOLN

Directed by John Ford • 1939

Aptly described by Dave Kehr in the Chicago Reader as a film that “stirs feelings about the American past that most of us, I suppose, have missed since childhood,” Young Mr. Lincoln is a deft portrait of the future president as a country lawyer and autodidact, winningly embodied by Henry Fonda. It might sound like hagiography, but any state-sanctioned sheen is quickly punctured by backwoods levity and unsentimental business. (Even when Lincoln takes on a legal case to illustrate that justice is a simple matter of right and wrong, he still wants to be paid.) If Lincoln’s greatness could be glimpsed when he was a young man, Ford and screenwriter Lamar Trotti suggest, it’s most evident in these unadorned moments of Abe splitting rails, judging pies, and cheating at tug-of-war. Lauded by Sergei Eisenstein as “daguerreotypes come to life,”Young Mr. Lincoln is a studio pastorale of the highest order. (KW)

100 min • 20th Century-Fox • 35mm from the Chicago Film Society collection at the University of Chicago Film Studies Center, permission Disney

Preceded by: “Ambition” (Hal Hartley, 1991) – 9 min – New 16mm print from the Chicago Film Society collection

Sunday, March 8 @ 7:00 PM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets: $12

BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN

Directed by Sergei Eisenstein • 1925

“I am a civil engineer and a mathematician … I approach the making of a motion picture in much the same way as I would the equipment of a poultry farm or the installation of a water system.” Eisenstein, like many of his Soviet contemporaries, professed an infatuation with mechanization, efficiency, and motion, and it’s telling that his most celebrated film has no real human “characters” in a conventional dramatic sense. He depicts a 1905 mutiny aboard a warship in the Black Sea, but treats the people like cogs in a larger system. (Cogs deserving of dignity, mind you!) The film itself is often overshadowed by the long tail of its influence and the endless analysis of its electrifying montage technique, but to experience Battleship Potemkin today is to be struck by an idiosyncratic quality that hoists the movie out of the world of film textbooks. Here is a highly personal work made by an obsessive 27-year-old, rightly convinced he was altering the course of world cinema. The strange rhythms of the montage still jar, and the smashing together of disparate images can still perplex. Legend has it Eisenstein was frantically editing his masterpiece until minutes before the premiere, cutting out frames and affixing splices with his own saliva. The print we’ll show is considerably more stable, but is no less a living, breathing fusillade of ideas and images that pulse with urgency, right down to the 108 frames of a fluttering flag colored by hand. (GW)

72 min • Mosfilm • 35mm from the Chicago Film Society collection

Preceded by: Hull of a Mess (Izzy Sparber, 1942) – 7 min – 16mm

Live musical accompaniment by Whine Cave (Kent Lambert & Sam Wagster)

Sunday, March 15 @ 11:30 AM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets: $11

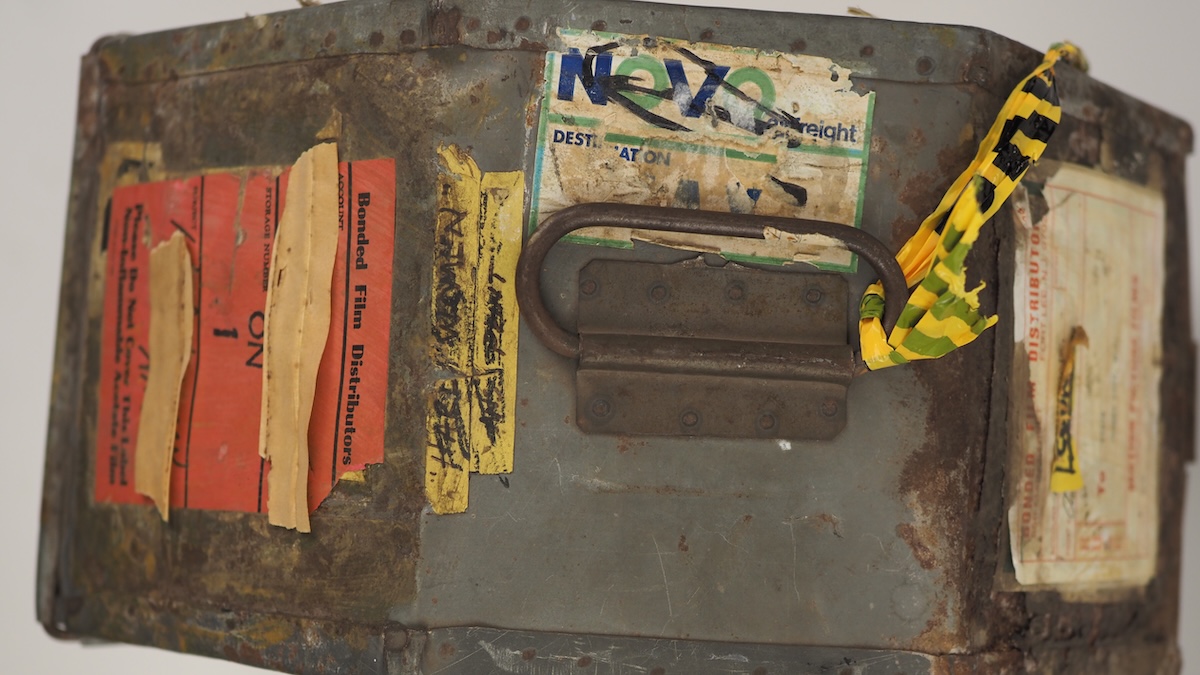

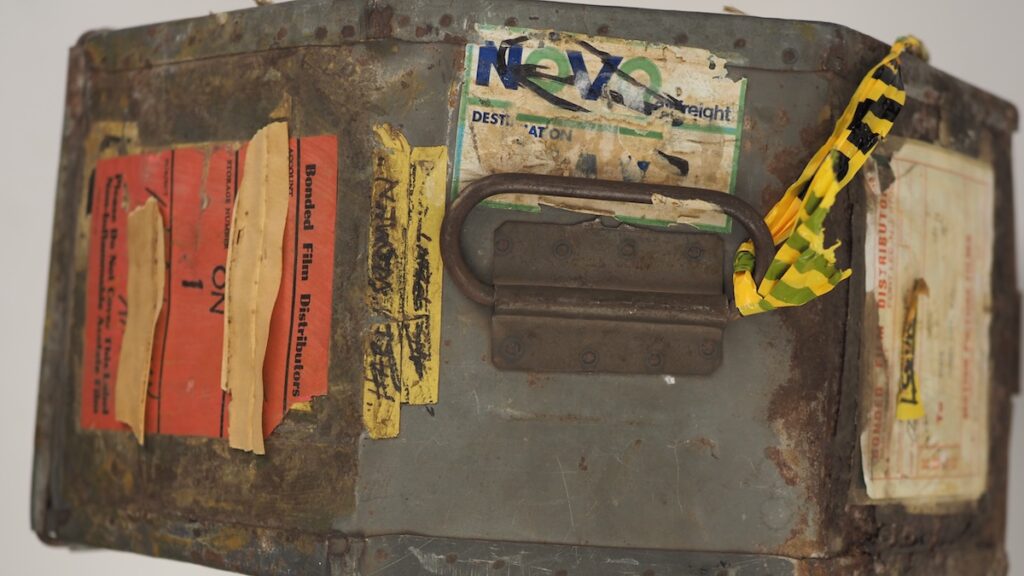

FILTH AND FREEDOM: SELECTIONS FROM THE VINEGAR SYNDROME FILM ARCHIVE

In the late aughts, young Chicagoan and Odd Obsession video counter clerk Joe Rubin began amassing a huge collection of vintage adult films on 16mm and 35mm and presenting series of rare film prints at Doc Films, including “American Regional Horror,” “The Golden Age of American Sexploitation: Forgotten Works from the Sexual Underground”, and “Cinevangelism: Evangelical Films from the ’70s and ’80s” (co-programmed with CFS cofounder Becca Hall). By 2012, Rubin and Ryan Emerson had founded Vinegar Syndrome, a genre film distribution company named for the term archivists and film collectors use to describe the (not remotely fun) chemical decomposition of acetate film base. Today, in addition to their many Blu-ray releases, Vinegar Syndrome has amassed an archive of close to 100,000 individual reels of film, spanning nearly every format and film gauge imaginable. It is the largest genre film-focused archive in the world and one of the largest non-institutional film archives in the United States. For this show, Joe Rubin and Vinegar Syndrome archivist Oscar Becher will join us to discuss the conservation and preservation work they do and to showcase selections from the Vinegar Syndrome Film Archive, including 16mm and 35mm shorts, trailers, and other demented oddities which haven’t seen the light of a projector in decades. (JA)

Approx 90 min • 16mm and 35mm from the Vinegar Syndrome Film Archive

This program is for adults only!

Wednesday, March 18 @ 8:00 PM

Constellation / Tickets: $15

QUICK BILLY

Directed by Bruce Baillie • 1970

Home movie. Landscape study. Abstract light show. Stag film. Rootin’ tootin’ homage to silent-era Westerns. Quick Billy, magnum opus of experimental filmmaker Bruce Baillie, defies easy classification. After founding the pivotal West Coast screening series and distribution co-op Canyon Cinema with savings from his job as a Safeway stock boy, Baillie spent much of the 1960s embodying the hippie dream, criss-crossing North America in his Volkswagen Beetle and shooting a number of the most beautiful 16mm films ever created. The trajectory of Baillie’s life and career changed when he moved into the Morningstar Ranch, an experiment in communal living where in 1967 Baillie and a number of other residents contracted severe cases of hepatitis. Baillie never fully healed from his illness, but the episode and a fortuitous encounter with The Tibetan Book of the Dead inspired him to film through his recovery, a years-long process that resulted in one of the most ambitious works of personal cinema ever conceived. Since its completion in 1970, Quick Billy has proven a lodestar for generations of filmmakers, inspiring the likes of Apichatpong Weerasethakul and George Lucas, and forging an entire visual vocabulary to be mined by Bolex-toting experimentalists for decades hence. Quick Billy will be followed by Quick Billy: Six Rolls, a series of “correspondences” with Stan Brakhage which Baillie described as “magic cousins” to his feature. (CW)

56 min • New 16mm restoration print, preserved by Anthology Film Archives

Followed by: “Quick Billy: Six Rolls (Numbers 14, 41, 43, 46, 47, and 52)” (Bruce Baillie, 1968-69) – 16 min – New 16mm restoration prints, preserved by Anthology Film Archives

Sunday, March 29 @ 6:00 PM

Gene Siskel Film Center / Tickets: $13

AH YING

Directed by Allen Fong • 1983

In Cantonese with English subtitles

Less known today after his disappearance into the wilds of local television and independent documentary cinema, director Allen Fong was considered one of the leading lights of the Hong Kong New Wave throughout the 1980s. While his better-remembered, more commercially oriented peers pushed the visual language of genre cinema to its outer limits, Fong’s films took a more naturalized approach, focusing on working-class characters and often pulling their narratives from their cast and crew’s real, lived experiences. Ah Ying, his international breakthrough, was inspired by the life of fish vendor-turned-actress Hui Sui-ying who stars as the titular main character. With its cast of nonprofessionals pulled from Hui’s real-life family and friends, Ah Ying is an especially committed exercise in verisimilitude, tracing the arc of Hui’s relationship with her artistic mentor and the beginnings of her stage and screen careers. Ah Ying will be preceded by an additional item from the Chicago Film Society collection: Theory of Achievement, a short film directed by Hal Hartley presented in a brand new 16mm print. (CW)

110 min • Feng Huang Motion Pictures • 16mm from the Chicago Film Society collection, permission Sil-Metropole Organization

Preceded by: “Theory of Achievement” (Hal Hartley, 1991) – 18 min – 16mm from the Chicago Film Society collection

Monday, April 6 @ 6:30 PM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets: $11

REDS

Directed by Warren Beatty • 1981

“The curious notion that Hollywood or its European counterparts could produce a truly and unequivocally progressive spectacle…continues to be as much a facet of Hollywood myth and its policy of containment as it is a popular utopian leftist dream.” Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum’s assertion in 1982 that “revolutionary” blockbusters are an impossibility (see also: 2025’s One Battle After Another) is a suggested discussion topic after CFS’s screening of Reds, Warren Beatty’s extravagant romance about American journalists and activists Louise Bryant and John Reed (witness to the Russian Revolution and author of Ten Days That Shook the World). While the film’s radicalism is questionable, it remains a glorious feat of filmmaking: a masterfully edited epic full of humanity, community, and wit (Elaine May was an uncredited contributor to the screenplay), where sexual liberation and revolution take place amid the joys and tedium of daily life, fiery domestic arguments, braising cabbage in the bathtub. Shockingly light on its feet even at 194 minutes, with a remarkable cast including Beatty as Reed and Diane Keaton as Bryant (in one of the most sensitive turns of her career), alongside Jack Nicholson as Eugene O’Neill and Maureen Stapleton as Emma Goldman. Scattered amongst the stars are interviews with real-life radicals, unnamed “witnesses” infusing the film with life and complicating it in ways that a lesser director would never have allowed. Bring your friends, your enemies, your lovers, and come prepared for a debate. (RL)

194 min + intermission • Paramount Pictures • 35mm from Paramount

Preceded by: Willie Howard & Al Kelly in “Come the Revolution” (1941) – 3 min – 16mm from the Chicago Film Society collection

Saturday, April 18 @ 11:30 AM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets $12

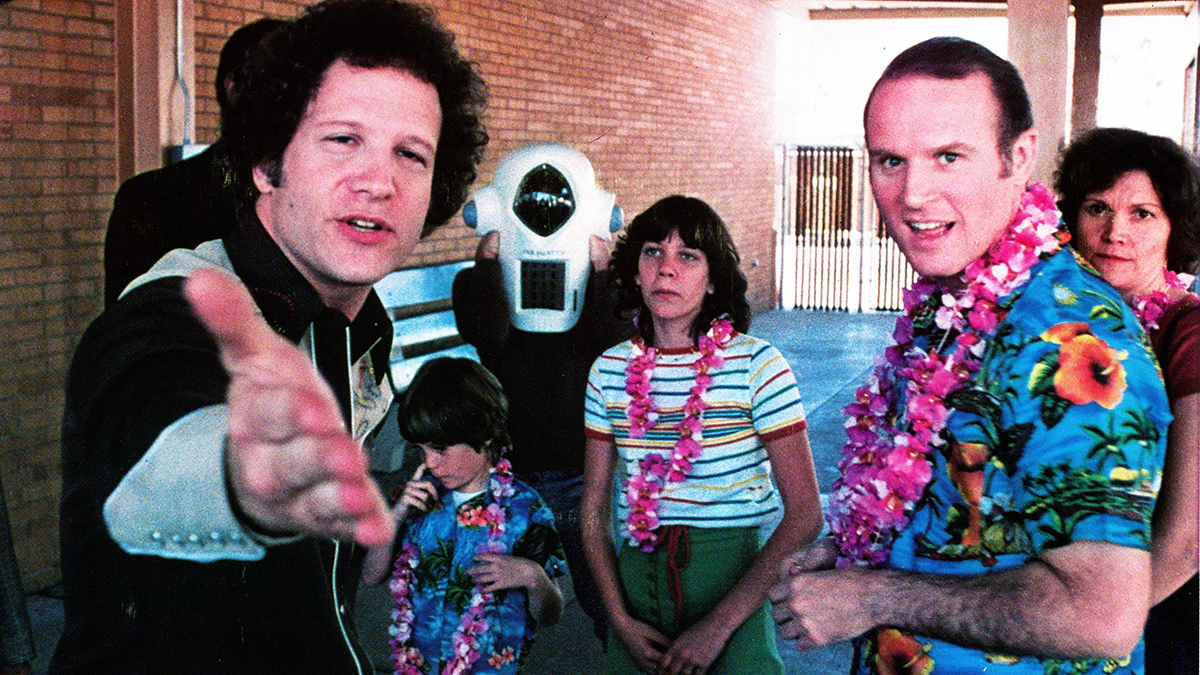

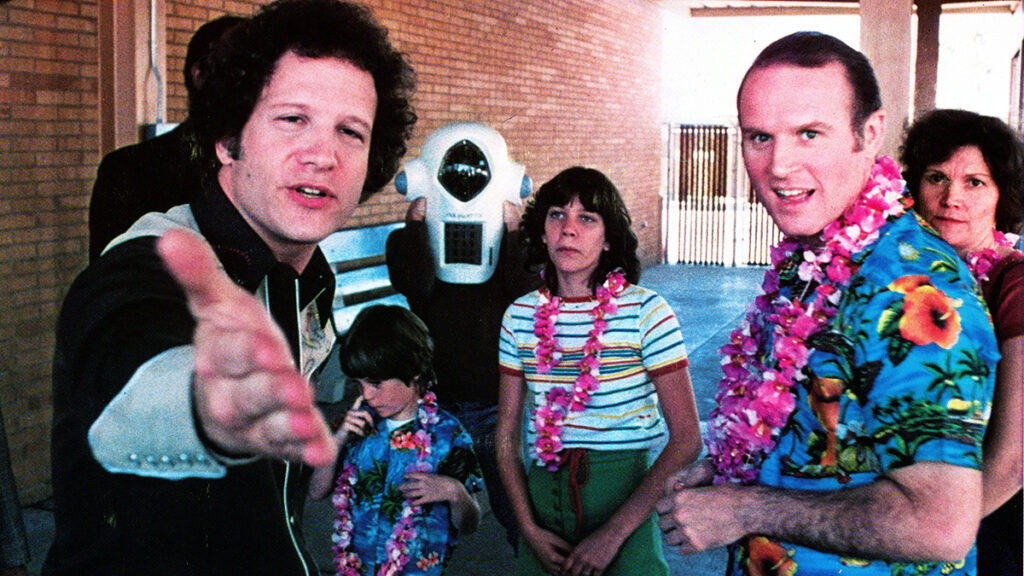

REAL LIFE

Directed by Albert Brooks • 1979

“I shouldn’t be allowed to do this! Why did I pick reality? I don’t know anything about it!” Albert Brooks, one of cinema’s greatest comic minds and director of some of our nation’s funniest social experiment pictures (Modern Romance, Lost in America, Defending Your Life) made his feature film debut with the independently produced mockumentary Real Life. Albert Brooks plays “Albert Brooks,” a comedian and wannabe documentary filmmaker — and the type of brazenly obnoxious, anxiety-riddled, joy-to-watch chaotic schmuck that would also appear in most of his later films. The premise (a satire of PBS’s 1973 An American Family, arguably the first “reality” TV show) is that the fictional Brooks has embedded himself in a family of four, selected from among thousands of applicants by the definitely real National Institute of Human Behavior, in a groundbreaking social experiment where he will film every moment of their daily lives. It goes spectacularly downhill. Brooks’s prescient film anticipates the onslaught of television’s most degrading genre, the morally bankrupt and grotesque slate of offerings that have poured endlessly from a spigot opened sometime in the ’90s. Owing in no small part to another great comic mind, Charles Grodin (as the father in Brooks’s guinea pig family), Real Life is still explosively, uncomfortably funny almost 50 years later. (RL)

99 min • Paramount Pictures • 35mm from Paramount

Preceded by: Real Life “3D” teaser trailer – 3 min – 35mm

Introduction and post-screening discussion with A. S. Hamrah, film critic for n+1, and author of The Earth Dies Streaming (n+1 Books). Hamrah has two new books out, Algorithm of the Night (n+1 Books) and Last Week in End Times Cinema (Semiotexte). Hamrah wrote the essay “Real Life: A Young, Honest Guy Like Himself” for the Criterion release of the film. This essay appears in Algorithm of the Night.

A. S. Hamrah writes for a variety of publications, including The New York Review of Books, Bookforum, Fast Company, and the Criterion Collection. From 2008 to 2016, he worked as a brand and trend analyst for the television industry, and he also produced a documentary feature which was the opening-night film at the Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight 2022. In addition, he has worked as a political pollster, a football cinematographer, and for the director Raúl Ruiz. He lives in New York.

Sunday, April 26 @ 6:00 PM

Gene Siskel Film Center / Tickets: $13

HENRY FOOL

Directed by Hal Hartley • 1997

A lonely garbageman named Simon Grim puts his ear to the ground in Woodside, Queens, and summons a scoundrel who will upend the lives of everyone around him. Henry Fool (“centuries ago it had an E at the end”) is a depraved horndog, a felon, a writer of a magnum opus (unfinished), and he cracks open Simon’s world like an egg. While Henry Fool contains all the humanist trappings of Hartley’s earlier films (deadpan humor, blue collar weirdos, artistic struggle), it deepens and darkens that work, going down a twisted path strewn with domestic violence, suicide, pedophilia, a ’90s version of MAGA, plus its fair share of excrement and puke. All of which makes CFS very proud to be the archival custodians of Hal Hartley’s 35mm films, including this one. Starring James Urbaniak as Simon, Thomas Jay Ryan as Henry, an underrated Kevin Corrigan, and always fabulous Parker Posey as Fay Grim – she of chronic bedhead and a bad attitude. (RL)

137 min • Possible Films • 35mm from the Chicago Film Society collection

Preceded by: “Share the Care” (Chicago Park District, 1941) – 2 min – 35mm from Chicago Film Society

“Share the Care” has been preserved by Chicago Film Society with the support of the National Film Preservation Foundation

☆ = PRE-CODE PICTURE PARTY

May 1 -3

The films of the early talkie era (1928–1934) play like a second founding of the seventh art, a moment when all the technical finesse, artistic pretense, and aspiration towards a universal visual language that characterized the final days of silent cinema were simply chucked away like yesterday’s garbage. Film had begun as an adjunct to vaudeville in the late 19th century, and the talkies would bring the overgrown art form promptly back to ground zero, a return to the immediacy and vulgarity of shysters, spielers, dames, and dancers talking at you. The slang and double entendres and unmodulated accents captured by the microphone — whether in English or another language — made the movies seem simultaneously more exotic and more pedestrian than ever, a technological marvel that simply brought audiences closer to the dumb jokes and earthy expressions that they might encounter on the street corner. Helped along by lax enforcement of the Production Code, Hollywood studios turned out a movie a week without much concern for good taste. These movies were shot quickly, slapped together, and released as soon as they were ready, for fear that their ultra-contemporary verve might wilt if left on the shelf too long. Hollywood needn’t have worried — they’re fresher than ever!

Co-presented with the University of Chicago Film Studies Center

Friday, May 1 @ 7:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆HORSE FEATHERS☆

Directed by Norman Z. McLeod • 1932

Huxley College’s new president is Quincy Adams Wagstaff (Groucho), and his idea of DEI is hiring middle-aged goofballs Baravelli (Chico) and Pinky (Harpo) as ringers to help Huxley’s football team win the big game. An urtext demonstrating how a handful of intuitively linked chaos agents can rearrange reality through wordplay and sheer disrespect, Horse Feathers showcases the Marx Brothers’ unerring instinct for upending institutional gravitas, and has influenced similarly anarchic comedies from Caddyshack to How High. Somehow, this slim film is also roomy enough to contain both the gleefully nihilist anthem “Whatever It Is, I’m Against It” and the genuinely tender trifle “Everyone Says I Love You.” (GW)

68 min • Paramount Pictures • 35mm from Universal

Preceded by: “Guido Deiro, The World’s Foremost Piano-Accordionist” (Doc Saloman, 1929) – 6 min – 35mm preservation print courtesy of the UCLA Film & Television Archive

Friday, May 1 @ 9:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆ LADIES MUST LOVE ☆

Directed by E. A. Dupont • 1933

Following the international success of his sordid carnival tale Variety (1925), Berliner Ewald André Dupont went on a globe-trotting tour, making movies in America, Britain, and France. By the early ‘30s, he was back in Germany, making big-budget talkies in multilingual versions for global consumption. His Jewish roots soon necessitated emigrating to America, where the renowned cosmopolitan was assigned B pictures, beginning with this energetic musical comedy, an attempt to cash in on the “gold digger” craze of the moment. Penned by Belvidere, Illinois native William Hurlbut, the story concerns a quartet of desperate gals who form a makeshift covenant, promising that whoever lands a sugar daddy must share her revenue with all four. Jeannie (June Knight) is the first to wrap an affluent stooge around her finger, but complications ensue: she might be (gasp!) falling in love with the mark. Despite a memorable “Tyrolean sequence,” the film didn’t quite catch on; Dupont went on a filmmaking hiatus at the end of the decade, and none of the four leading ladies would make another movie after 1943. (GW)

70 min • Universal Pictures • 35mm from Universal

Saturday, May 2 @ 3:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆THE LETTER ☆

Directed by Jean de Limur • 1929

W. Somerset Maugham’s play The Letter was a salacious sensation in 1927, with its tale of an adulterous wife in Singapore who murders her lover when he takes on another mistress. Katharine Cornell originated the role of Leslie Crosbie on Broadway, but Jeanne Eagels took over the job when it came time to adapt the property to the newly audible screen. It was a lucky break for Eagels: the volatile actress had recently been suspended from Actors Equity, which effectively barred her from working on Broadway and forced her to seek employment elsewhere. Eagels had already starred in a few silent films, but none of them afforded her the opportunity to present her raw performance style with the immediacy seen here. (By the end of 1929, she would be dead from a drug overdose.) The first talkie filmed at Paramount’s East Coast studio in Astoria, The Letter was an improbable, almost experimental production: direction was entrusted to a novice from France and the facility had not yet been fully prepped for professional sound recording. Remade in 1940 with Bette Davis and the edges sanded down for Production Code compliance, this first version of The Letter remains notable as Eagels’s only surviving talkie — and what a showcase it is. Mordaunt Hall warned in The New York Times that Eagels’s climactic scene was “a severe test of the audible device.” Challenge accepted! Restored by the Library of Congress and the Film Foundation with funding from the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. (KW)

60 min • Paramount Pictures • 35mm from Library of Congress

Preceded by: “Dangerous Females” (William Watson, 1929) – 21 min – 16mm from the Chicago Film Society collection

Saturday, May 2 @ 5:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆ THE WISER SEX ☆

Directed by Berthold Viertel • 1932

Margaret (Claudette Colbert) doesn’t want to marry a man who’d prioritize his job over their relationship — not even if he’s a district attorney (Melvyn Douglas) on the trail of the ruthless gangster Harry Evans (William Boyd). But when Margaret finds that the hapless D.A. has been framed by Evans for the murder of his own cousin (Franchot Tone), she’s forced to go undercover as a blonde good-time gal and expose the truth. If only a jury of the ‘wiser sex’ could be impaneled, justice might just prevail. One of the last films produced by Paramount at their Astoria studio, The Wiser Sex epitomizes a bold, brassy style of East Coast filmmaking. Despite working from a play from 1905 that had been filmed twice already, director Berthold Viertel valiantly tried to spin his version as a ripped-from-the-headlines gloss on the then-current Seabury investigations of New York political corruption. (KW)

76 min • Paramount Pictures • 35mm from Universal

Saturday, May 2 @ 8:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆ WILD BOYS OF THE ROAD ☆

Directed by William A. Wellman • 1933

William Wellman’s sleek, gritty melodrama about teenagers faced with the reality that their parents don’t have enough money to feed them stars Frankie Darro and Edwin Phillips as two high school sophomores who leave home in search of work. Trainhopping their way through the Midwest, they meet several other orphaned teenagers — among them Dorothy Coonan, who was doing fine until her aunt’s brothel was shut down — and ride from town to town and slum to slum as they are run out by the terrifying local authorities. Few people worked as efficiently in pre-Code Hollywood as “Wild Bill” Wellman, who often balanced a strong social conscience with as much sex, violence, and humility as could fit into a six- or seven-reel feature. His work for First National and Warner Brothers in the early ’30s represents much of what made movies as important as they were during the Depression. (JA)

68 min • Warner Bros. Pictures • 35mm from the Library of Congress, permission Warner Brothers

Preceded by: “Their First Mistake” (George Marshall, 1932) – 21 min – 35mm from the Library of Congress

Sunday, May 3 @ 1:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆ HIS WIFE’S LOVER ☆

Directed by Sidney M. Goldin • 1931

In Yiddish with English subtitles

The arrival of the talkies didn’t just open ears to American English vernacular, but presented an unprecedented opportunity for immigrant communities to hear their own patois at the movies. Promoted as the “first 100% Yiddish singing and talking picture,” His Wife’s Lover was a vehicle for Ludwig Satz, a real-life music hall star who plays the fictional music hall star Eddie Wien. Eddie’s unscrupulous uncle Oscar (Isidore Cashier) resents and mistrusts women, and bets his nephew that vivacious Golde (Lucy Levine) would marry any random wealthy suitor, just like any gold digger. Eddie disguises himself as an embarrassing caricature of decrepit capital, loses the bet by winning the reluctant Golde, and then loses anew when his bride refuses to consummate their marriage. Can Eddie double-down on his wager, Safdie-style, and win Golde back as himself? Shot in nine days, His Wife’s Lover emerged as a deliriously entertaining musical — and racy enough to rival any pre-Code Hollywood mishegoss. (KW)

80 min • High Art Pictures Corp. • 35mm from the National Center for Jewish Film

Sunday, May 3 @ 3:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆ CARAVAN ☆

Directed by Erik Charell • 1934

Being a Hungarian countess is annoying. Servants follow you around making sure you follow all the dumb ancient traditions — that is, until you turn 21. Then, if you’re like Wilma (Loretta Young, actually 21 at the time), you’ll inherit your dad’s estate and you can make your own rules, but only if you’re married. Ugh! Living as a “gypsy,” however, is a little more relaxing, as Latzi (Charles Boyer, in a star-making turn) can attest. Life is filled with music, you sleep under the stars, and your heart bursts with passion and wanderlust. The downside is, people are always accusing you of stealing, and sometimes you fall in love with a countess who doesn’t know you exist. This is Hollywood, though, so their worlds are about to collide; when they do, it’s with a surprising gentleness and patience. Director Charell, who’d just escaped Nazi Germany, guides us through the contrived reality-show premise with a light and romantic touch, drenched in sweet musical motifs and delicate balletic gestures. (GW)

102 min • Fox Film Corp. • 35mm from the Museum of Modern Art, permission Criterion Pictures, USA

Sunday, May 3 @ 6:00 PM

Logan Center for the Arts / Tickets: $10

☆ ANYBODY’S WOMAN ☆

Directed by Dorothy Arzner • 1930

Dorothy Arzner and co-writer Zoe Akins (Working Girls, Christopher Strong) had a knack for imbuing their pictures with more complexity, emotional intelligence, and proto-feminist nuance than most contemporary male-driven studio fare. This one, a slippery sort of comic melodrama with a side of dry social satire, gives us the memorable Pansy Gray (Ruth Chatterton), a down-and-out former showgirl tired of bouncing from dead-end job to degrading hustle amid the Depression-era gig economy. We first meet her sprawled bare-legged across an overstuffed chair in a sweltering Manhattan hotel room, belting out a melancholy blues (she knows her way around a ukulele!). Listening from a nearby open window is heartsick Delaware attorney Neil Dunlap (Clive Brook), blackout drunk and unusually receptive to Pansy’s earthy charms. An impromptu hotel party ensues, and the next morning Pansy and Neil wake up having drunkenly wed; to make their marriage work, both must now navigate different gauntlets of shame and prejudice. Paul Lukas, who’d later pair with Chatterton so memorably in the similarly twisty Dodsworth, shines here as a wealthy rival for Pansy’s affection. (GW)

80 min • Paramount • 35mm from UCLA Film & Television Archive, permission Universal

Preceded by: “The Golf Specialist” (Monte Brice, 1930) – 20 min – 35mm

Saturday, May 16 @ 11:30 AM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets: $12

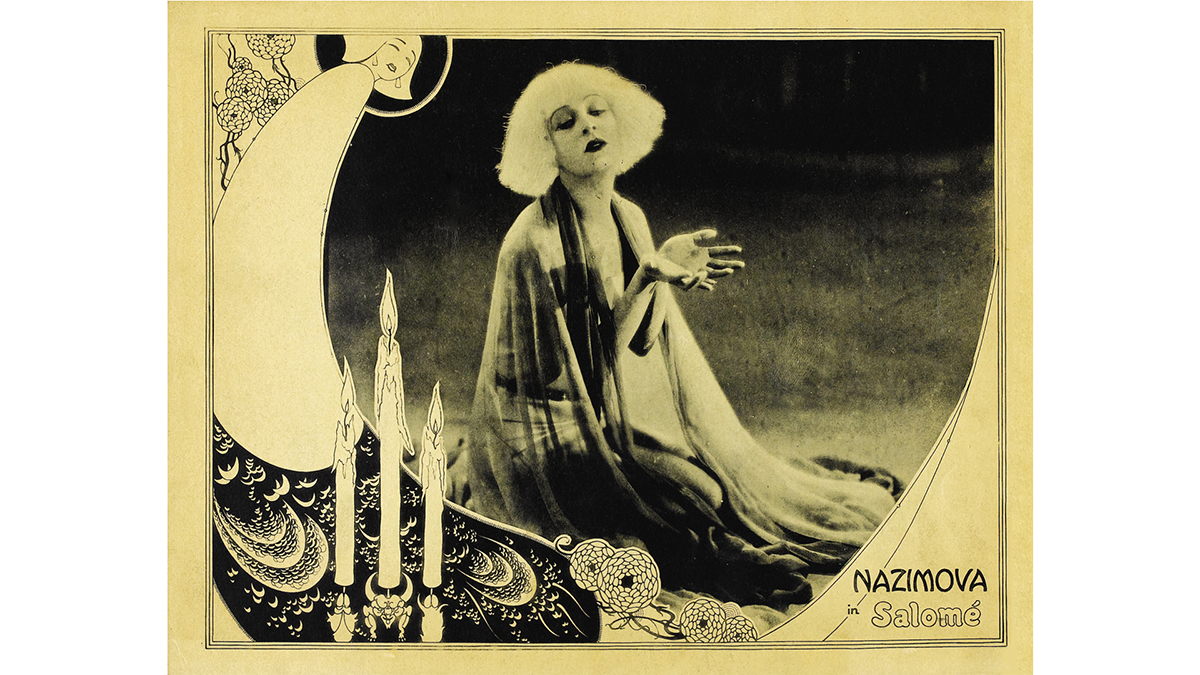

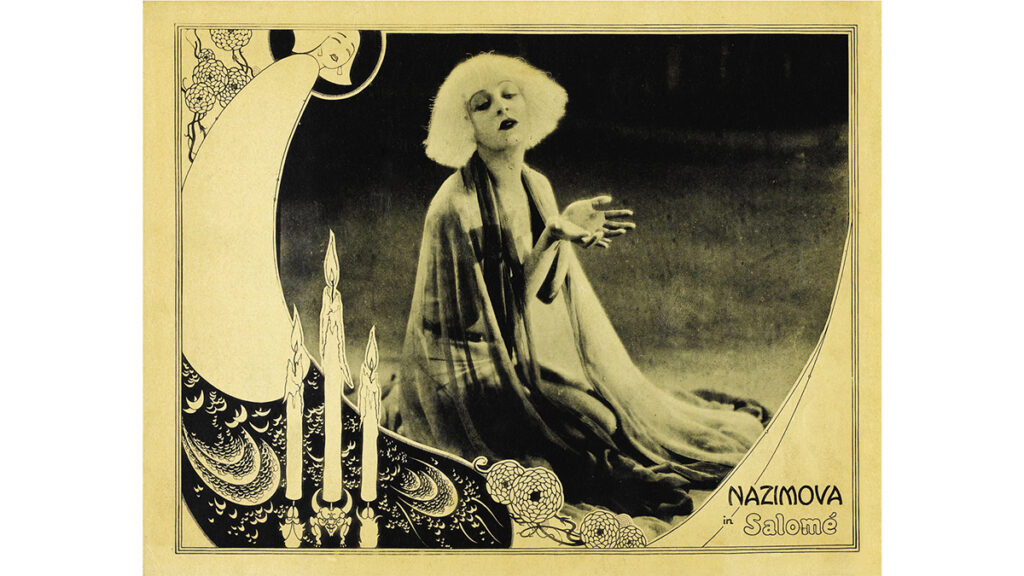

SALOMÉ

Directed by Charles Bryant • 1922

In 1922, renowned Russian stage and screen actress Alla Nazimova committed the extraordinary sum of $350,000 to produce Salomé, a film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s popular play — directed by, written by (under a male pseudonym), and starring herself. Although a woman of forty-two, Nazimova convincingly plays the teenage Salomé, who performs the Dance of the Seven Veils in exchange for the head of Jokanaan. The film unfolds through a series of posed tableaux, deliberate movements, and highly stylized sets, resisting realism and traditional narrative action and embracing the fabulous. Photoplay cautioned that it was “a hothouse orchid of decadent passion… You have your warning: this is bizarre stuff”. Officially “directed” by her husband Charles Bryant, Salomé was largely shaped by Nazimova herself, with Bryant serving as both marital and professional beard. In his notorious Hollywood Babylon, Kenneth Anger insinuated that Salomé was made with an all-queer cast and crew — an unverifiable claim that nevertheless summons the essence of the film’s decadent flamboyance. Salomé contains no explicitly queer characters, but its sensibility emerges from a network of artists whose identities and desires had to remain unspoken. Though the film was a financial and critical disaster and effectively ended Nazimova’s Hollywood career, it resurfaced as a cult object in the 1970s when it was double-billed with Broken Goddess, starring Holly Woodland. Seen a century on, Salomé offers a record of how queerness circulates through aesthetics, rumor, and history, inviting modern audiences to read between the frames. (TV)

74 min • Nazimova Productions • 35mm from George Eastman Museum

Preceded by: “Overstimulated” (Jack Smith, 1959-63) – 5 min – 16mm from Canyon Cinema

Live musical accompaniment by the MIYUMI Project Japanese Experimental Ensemble

Sponsored in part by Asian Improv aRts Midwest.

Monday, May 25 @ 7:00 PM

Music Box Theatre / Tickets: $11

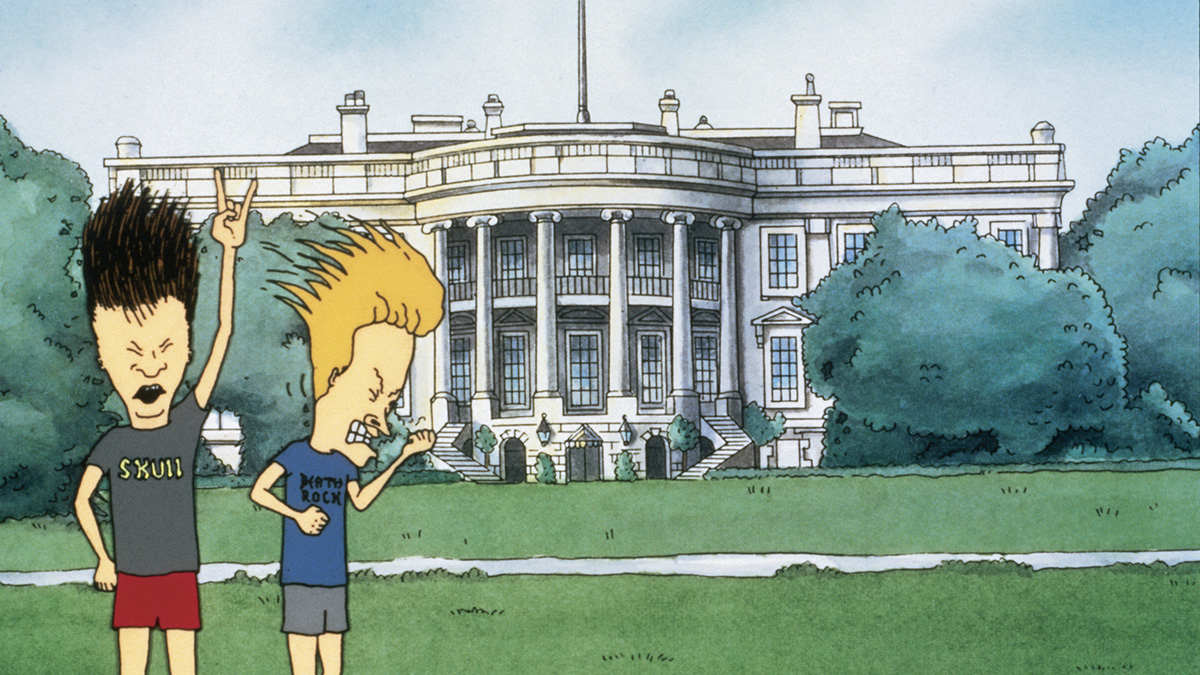

BEAVIS AND BUTT-HEAD DO AMERICA

Directed by Mike Judge • 1996

Spawned from the wilds of underground animation, teenaged delinquents Beavis and Butt-Head first appeared in 1992 in a pair of 16mm shorts made by Mike Judge for a few hundred dollars with a simple Bolex camera. Over the following five years, the pair would become cultural phenoms, anchoring MTV’s flagship series, inspiring public outcry over a number of dubiously connected acts of childhood violence, and eventually going Hollywood, starring in their own blockbuster 35mm theatrical feature, Beavis and Butt-Head Do America. Their lives to date spent in cathode ray-illuminated squalor, making fun of brainy college rock and flaccid fantasy metal videos, Beavis and Butt-Head awake one afternoon to horror beyond any comprehension: their television set has been stolen. Thus begins an odyssey that will find the boys criss-crossing the United States of America, experiencing the greatest natural and cultural wonders this nation has to offer, embroiling themselves in shady criminal plots, and coming into contact with the upper echelons of political power, all of which they respond to with transcendently puerile dick and poop jokes. Bow down to the almighty bunghole! Prior to the feature, we will be screening a rare 16mm print of Wes Archer’s obstreperous animated short Jac Mac & Rad Boy Go!, a key influence on Mike Judge’s early filmmaking career. (CW)

81 min • MTV Films • 35mm from the Chicago Film Society collection, permission Paramount

Preceded by: “Jac Mac & Rad Boy Go!” (Wes Archer, 1985) – 4 min – 16mm from Wes Archer

Sunday, May 31 @ 6:00 PM

Gene Siskel Film Center / Tickets: $13

FLY AWAY HOME

Directed by Carroll Ballard • 1996

Best known for The Black Stallion, director Carroll Ballard displays a wildly undervalued talent for making serious family pictures that achieve a Days of Heaven level of grace. Fly Away Home is based on the real-life story of sculptor Bill Lishman, who taught orphaned geese to learn migration patterns by training them to follow him in an ultralight aircraft. The fictionalized adaptation of Lishman’s autobiography stars Anna Paquin and Jeff Daniels as a reunited daughter and father whose relationship is repaired by guiding a flock of geese from Ontario to North Carolina. Sixty geese were raised and trained on the set of this deeply moving and often breathtaking portrait of humans attempting to do right by nature. Fly Away Home amazed kids and adults alike, including the Chicago Reader‘s Jonathan Rosenbaum, who wrote: “At a time when so few American movies believe in anything, it’s cheering and satisfying to see one that believes in geese.” (JA)

107 min • Columbia Pictures • 35mm from the Chicago Film Society collection, permission Sony Pictures Repertory

Preceded by: “Birds of Chicago” (1939) – 10 min – 16mm from the Chicago Film Society collection

Programmed and Projected by Julian Antos, Becca Hall, Rebecca Lyon, Tavi Veraldi, Kyle Westphal, and Cameron Worden.

Ambassador / Additional Capsules: Gabriel Wallace

The Chicago Film Society is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. CFS acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

Heartfelt thanks:

Brian Andreotti, Will Morris, & Ryan Oestreich of the Music Box Theatre; David Antos; Wes Archer; Canyon Cinema; James Bond of Full Aperture Systems; Justin Dennis of Kinora; Jack Durwood & Emiah Washington of Paramount Pictures; Christy LeMaster, Brennan McMahon, & Michael Wawzenek of the Gene Siskel Film Center; Cary Haber of Criterion Pictures, USA; A.S. Hamrah; Jason Jackowski of Universal Pictures; John Klacsmann of Anthology Film Archives; Catherine Lam of Sil-Metropole Organization; Gabrielle Lyon; Tristen Ives, Jane Keranen, Douglas McLaren, & Ben Ruder of the University of Chicago Film Studies Center; the Media History Digital Library; Nicole Muto-Graves & Mike Reed of Constellation; Mike Quintero; Beth Rennie, Jared Case, & Jeffrey Stoiber of George Eastman Museum; Joe Rubin & Oscar Becher of Vinegar Syndrome; Kat Sachs; Katie Trainor, Seth Mitter, & Dave Kehr of the Museum of Modern Art; Nancy Watrous, Olivia Babler, Justin Dean, & Mickey Gral of Chicago Film Archives; Kathryn Wilson; and Hannah Yang. Particular thanks to CFS board members Brian Ashby, Raul Benitez, Mimi Brody, Steven Lucy, Brigid Maniates, Douglas McLaren, Patricia Ledesma Villon, & Artemis Willis, and CFS advisory board members Brian Block, Lori Felker, Brian Meacham, & Andy Uhrich.

And extra special thanks to our audience, who make it all possible!

And extra special thanks to our audience, who make it all possible!