Last year we presented a two-part analysis of trends and achievements from the preceding twelve months of cinema. Here’s this year’s edition. — Ed.

Nothing But a Man, the independent feature from 1964 about apartheid conditions in the American South, plays in a new print at the Gene Siskel Film Center this weekend. It’s worth seeing for many reasons, but let’s focus on one detail. It opens with a peculiar credit, made no less disconcerting by the intervening five decades; instead of announcing itself as the product of a film studio, television station, or the star’s vanity label, Nothing But a Man cites the DuArt Film Laboratories as its putative producer.

This is, of course, literally true—DuArt developed the latent image recorded on the original camera rolls and then struck intermediate elements that facilitated the release prints distributed to theaters. In the most industrial sense, they produced the object to be consumed. (Amy Taubin suggests a less totalizing explanation in Artforum: Irvin Young, brother of Nothing But a Man producer/cinematographer/co-writer Robert M. Young, ran DuArt and probably offered free or steeply discounted lab services to the shoestring production.)

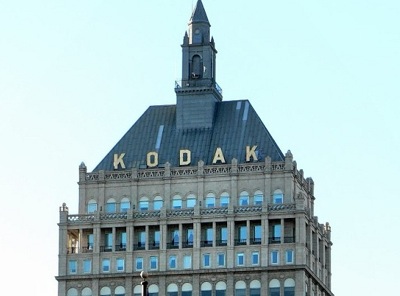

We don’t often talk about film laboratories in such exalted terms, and the opportunities to do so are quickly diminishing. Although 2012 saw no shortage of elegies, editorials, and think pieces about The Death of Cinema, the discussion was mostly confined to cranky complaints about the inanities of the latest blockbuster or the way “kids these days” are content to watch movies on their iPhones. Kodak’s long-anticipated bankruptcy announcement in January occasioned many end-of-an-era pronouncements, but too few attempts to grapple with the bigger picture.

Film historians will likely look back on 2012 as the year that spelled the death knell for film as a mass medium. At the time of Kodak’s Chapter 11 filing, Japanese competitor Fujifilm was touted as a healthy rival whose savvy business decisions had allowed it to weather the industry-wide switch to digital. Talk about savvy: by September, Fuji announced that they would cease production on nearly all their film stocks.

In American movie theaters, the digital conversion continued at startling speed, with all but the smallest and worst-capitalized houses making the switch before year’s end. (Many European territories had already reached total compliance.) Specialty laboratories shuttered, including Amsterdam’s venerable Haghefilm and its parent company, Cineco. (Two weeks ago came news—on facebook, no less—that the lab would re-launch as Haghefilm Digitaal, though its future obviously remains precarious.)

In American movie theaters, the digital conversion continued at startling speed, with all but the smallest and worst-capitalized houses making the switch before year’s end. (Many European territories had already reached total compliance.) Specialty laboratories shuttered, including Amsterdam’s venerable Haghefilm and its parent company, Cineco. (Two weeks ago came news—on facebook, no less—that the lab would re-launch as Haghefilm Digitaal, though its future obviously remains precarious.)

Before wading into the implications of these events, let’s examine the reaction. There were nostalgic laments for vanished perfection of photochemical monochrome, such as Daniel Eagan’s piece in The Atlantic, and photo-essays about the disappearing projection booth in Wired. Programmers tabulated the ratio of DCP-to-35mm screenings at major international festivals and shared the results with colleagues on facebook. Archivists argued privately (and sometimes all-too-publicly) about the stability of digital storage and the quality of digital projection. Our own Rebecca Hall even participated in a panel about conserving analog projection equipment at the annual Association of Moving Image Archivists conference in December.

These conversations assumed, sincerely but somewhat naively, that the future of film was in the hands of those who cared about it most. That is, curators, archivists, programmers, projectionists, filmmakers, collectors, and critics could band together and will a reprieve, or at least stipulate the terms of a plea bargain. Film would remain viable, even if it meant we all had to become machinists or open our own DIY labs or petition the studios to maintain 35mm libraries or order enough raw stock to beat back the red ink in Kodak Park.

• • •

Who will step up to save cinema? In 2012, Christopher Nolan and Paul Thomas Anderson attempted nothing less.

Who will step up to save cinema? In 2012, Christopher Nolan and Paul Thomas Anderson attempted nothing less.

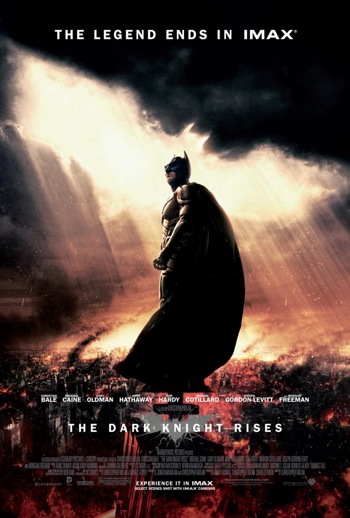

Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises was shot entirely on film, including over 70 minutes worth of footage on the gargantuan, 15-perforation, horizontal 70mm IMAX film. Anderson’s The Master was lensed almost exclusively on 5-perforation, vertical 65mm. (The mute 65mm negative becomes the basis for a 70mm print with the addition of a soundtrack, so it will be referred to as 70mm hereafter.) Both were assembled with conventional analog workflows, with parallel Digital Intermediates also made to serve the marketplace.

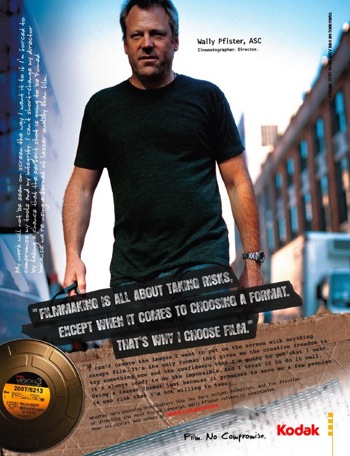

It’s easy to spout Kodak’s ‘Film—No Compromise’ slogan, but it’s also undeniable that substantial market forces are militating against giving audiences that choice.

Nolan’s clout and the extraordinary anticipation that preceded The Dark Knight Rises were sufficient to convince IMAX to reboot or reinstall 70mm projection systems in select venues, even though the giant-screen company had been converting many of its site to digital exhibition. Anderson was less successful. The Master played an extended 70mm engagement at New York’s Village East Cinema but its large-format play-off in other markets has been spotty. Chicago has so far seen only one 70mm screening—a pre-release show at the Music Box that sold out in twenty minutes. And that wasn’t the distributor’s idea. The Music Box screening was brought about almost single-handedly by the indefatigable Ben Kenigsberg of TimeOut Chicago, whose blog posts on the subject attracted Anderson’s attention.

To be on Southport that night and see hordes of young people photographing the 70mm marquee made one boundlessly optimistic about public awareness of film exhibition. The next day, Michael Phillips reviewed the show in the Chicago Tribune:

Opening this film wide, in conventional projection formats, is a mistake. It’s not “The King’s Speech.” It’s not “The Artist.” It’s not half as “easy” as Anderson’s previous film, the inspired “There Will Be Blood.” Based on last night’s 70mm screening, the question’s inevitable: Why wouldn’t Weinstein go out of its way to treat this exotic bird with care and to maximize interest and availability in experiencing “The Master” in optimum 70mm circumstances? That’s how he shot it (mostly), and that’s how it should be seen (when and where possible).

People do care about the way they receive images. They want to know they’re getting a good look at a filmmaker’s intentions. “The Master” is an analog novelty. It’ll look good when projected digitally, but not this good.

Phillips wasn’t the only one. The internet swelled with 70mm paeans, primers, and pleas. For a whole generation of cinephiles—the ones raised on Pulp Fiction, Memento, Amélie, Anderson’s own Magnolia, and the endless intertextual swirl of DVD commentaries, making-of docs, and director’s cut—this was the first time they’d been called upon to recognize and fight for film exhibition, 70mm or otherwise.

The Music Box has yet to secure a return engagement for The Master in 70mm. The Weinstein Company typically gives first dibs to chains like Landmark for its major releases, effectively shutting out the only public venue in town equipped for 70mm. The Master didn’t even play anywhere in Chicago in 35mm until the Patio booked it as a second-run title.

The Music Box has yet to secure a return engagement for The Master in 70mm. The Weinstein Company typically gives first dibs to chains like Landmark for its major releases, effectively shutting out the only public venue in town equipped for 70mm. The Master didn’t even play anywhere in Chicago in 35mm until the Patio booked it as a second-run title.

Reviews of The Master tended to treat it as a referendum on Anderson’s place in the pantheon—was it an exasperating masterpiece that earned comparison to Kubrick or merely exasperating? I suppose it’s only appropriate that The Master spawn a cult of personality, but film criticism might concern itself with more interesting matters. (Is it edifying to walk out of a movie and declare its maker a genius? Or quibble with your friends about the degree of that genius?)

Whatever else it is, The Master is a film of extraordinary and mysterious ambitions with an unusual integration of thematic concerns and formal strategies. The period recreation is expert, and something more: a plausible account of the social milieu of a righteous minority in mid-century American life, cajoling strangers with leaflets and cozying up to tranced-out dowagers. Though pre-release buzz marked The Master as a Scientology éxposé, the film is actually ambivalent, if not outright sympathetic, towards The Cause as packaged by Phillip Seymour Hoffman. It’s a cult, but it’s also positioned as one of the few forces of organized pacifism in Cold War America. The Cause’s turgid catechism is equally an instrument of enslavement and liberation—it’s the thing finally allows Joaquin Phoenix to relate honestly to another person.

“Laughing at [Scientology] or being negative, that goes away so quickly when your head is inside it,” Anderson recently told the New York Times “and you see how people are talking about getting better and taking control of their lives.” I don’t like metaphors, but it’s not inapt to ask whether 70mm is Anderson’s Cause. Clarity is its own cult. Composed largely of close-ups, rather than the wide angle spectacles that had hitherto been 70mm’s specialty, The Master is itself a fantastic appropriation and an impossible crusade—a private reckoning in the public square. Can a whole system of consciousness be overthrown? What about a whole system of film exhibition?

• • •

Until the 1960s or so, film critics often took it upon themselves to not only champion individual works but to defend the whole system of cinema as a fertile and substantial medium for serious art. Cinema was not—or at least not always, or not only—a witless form of industrial entertainment, but really a means to personal expression and a playground of submerged dramatic, psychological, sexual, and kinetic insight. Hack directors became invaluable auteurs.

This film-as-art operation was a necessary corrective to a certain snobbish tendency in cultural criticism that endeavored to divide everything into opposing camps: high art vs. low, art vs. kitsch, masterpiece vs. trash. And yet today it’s reasonable to ask whether this wholesale shift to the artist—to his (and, far too infrequently, her) themes, strategies, opinions, and claims to creating lasting masterworks—hasn’t left the medium itself out in the cold. In an effort to disavow the commercial, the industrial, the mass-produced character of cinema, we may wind up destroying the artist as well.

This film-as-art operation was a necessary corrective to a certain snobbish tendency in cultural criticism that endeavored to divide everything into opposing camps: high art vs. low, art vs. kitsch, masterpiece vs. trash. And yet today it’s reasonable to ask whether this wholesale shift to the artist—to his (and, far too infrequently, her) themes, strategies, opinions, and claims to creating lasting masterworks—hasn’t left the medium itself out in the cold. In an effort to disavow the commercial, the industrial, the mass-produced character of cinema, we may wind up destroying the artist as well.

I may want to make films, but what if the means to do that are becoming extinct?

The promise of the DIY laboratory greatly underestimates the craft, expertise, and complexity of modern lab work. Hand-processed film stock often yields startling qualities on-screen (vide Ben Rivers’s Two Years at Sea), but such effects are not appropriate for every production. Faithfully translating a decades-old negative to a new print often demands the interpretative sensitivity of a medievalist: examining notches cut into the side of the negative or staples affixed to its perforations to determine the proper contrast values in the printer, decoding similar ‘signs’ to assure that fade-ins and fade-outs occur as planned, guiding shrunken material through an optical printer for maximal stability, repairing decades-old cement splices, agitating the developer with attention to the particular eccentricities of a given film stock, achieving perfect synchronization between sound and image. Such skills are the stuff of apprenticeship and further years of trial and error. They cannot be summoned anew overnight.

Labs provide general services, but many also pursue certain specialties, like 16mm blowup, audio restoration, tinting, etc. Up until now, archivists and filmmakers have had the privilege of working with many labs and selecting the right partner for a particular project based on its expertise. The old Haghefilm, for example, boasted of a special 28mm gate that allowed its technicians to transfer the contents of the obsolete non-theatrical gauge to conventional 35mm. (Our friend Dino Everrett would contest the ‘obsolete’ label being applied to his beloved 28mm, but his revival of this special format is the subject of another column.)

The skills passed down through generations of lab technicians are not facing imminent eradication. Some specialty labs, like Cinema Arts and the much larger FotoKem, are still going strong; and should the day come when the last for-profit lab proves unsustainable, America will always have in-house lab facilities affiliated with its two largest film archives, the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Presumably, their insulation from market pressure will act as a bulwark against the complete disappearance of quality lab work.

But even labs operating in the public trust need film stock. Will we need a non-profit manufacturer to go with them?

High-quality lab work requires a diverse array of stocks: black-and-white negative stock differs from black-and-white fine grain (or interpositive) and differs again from black-and-white print stock; specialized formulations and workflows reduce the sibilant distortion of the optical soundtrack; camera stocks of different speeds yield different grain structures.

High-quality lab work requires a diverse array of stocks: black-and-white negative stock differs from black-and-white fine grain (or interpositive) and differs again from black-and-white print stock; specialized formulations and workflows reduce the sibilant distortion of the optical soundtrack; camera stocks of different speeds yield different grain structures.

Over the last decade, Kodak has radically scaled back the variety of stocks on offer. The latest victim is 16mm Ektachrome reversal, the high-quality amateur format. Should the company survive, would it see enough profit to continue producing all these secondary and tertiary stocks? (This much is clear: Kodak CEO Antonio Perez has long touted inkjet printing, not film manufacture, as the company’s salvation—or at least he did until Kodak axed its desktop printer line in September.) Fuji, which never tried competing with Kodak on all but the most popular stocks, has exited the stage entirely.

Can cinema be saved? Not until we acknowledge the character of what we’re dealing with. The tension between personal expression, corporate profit, artisanal craft, industrial economy-of-scale, technological innovation, built-in obsolescence, and physical frailty and decay is what makes film worth talking about in the first place.