Friends enthuse daily about the treasures they’ve found on Netflix Instant. Old media salutes new, with print critics prophesying a day “before too long [when] the entire surviving history of movies will be open for browsing and sampling at the click of a mouse.” For some, the day has already arrived. “This instant, sitting right here,” Roger Ebert recently observed, “I can choose to watch virtually any film you can think of via Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, MUBI, the Asia/Pacific Film Archive, Google Video or Vimeo.”

The annual trip to Syracuse teaches a very different lesson. Now in its 31st year, the shoestring festival known as Cinefest (organized by the dozen or so members of the Syracuse Cinephile Society) suggests not only an alternate history of cinema but also of cinephilia. I have seen the future and it is a conference room at the Holiday Inn.

Despite a few 35mm titles (screened at the Palace in downtown Syracuse), Cinefest is endemically a 16mm event. Towards the back of this conference room, there’s a platform with two Eikis projectors–table-top classroom workhorses monstrously tricked-out and hot-rodded with new take-up arms, rattling away. (When the Eikis were briefly silenced by a video projector installed to show off some new restorations as yet available only as digital files, that rattle was much missed; in fact, its abundant absence prompted the ejection of the film inspection bench from the make-shift auditorium. The rewind squeaked too audibly without the comfortable trill of the projectors to drown it out.)

The prints screened are often as old as the films themselves—beautifully tinted, diacetate Kodascope reels can usually be found on the bill. (They aren’t necessarily promoted as such in advance, so there’s always a collective gush when one hits the screen.) Some of the prints are quite damaged—splicey, scratched, warped, shrunken, otherwise inhospitable. Most of them come from collectors and it’s not uncommon to hear their owners offer chipper warnings such as, “I think this is the only print, but it should run. In any case, I won’t blame you guys if it breaks.”

“They were rare, but not necessarily good,” remarked one friend, a first-time attendee. Yes, but—how often do we find ourselves watching films that are neither rare nor good? The thing that the Cinefest films tend to share is a sense of dogged indistinctness and unsalable marginality—vehicles for forgotten theatrical stars, B programmer dress-downs of A genre and material, the only extant film from a short-lived production company, minor examples of major cycles, fragmentary silents, creaking talkies. In short, they are the kinds of films that no one—not least the rightsholders—is endeavoring to preserve, much less restore, release, license, stream, or promote. One wonders whether the owners even know about these assets.

In many ways, the films now belong more to the collectors than the producers. That they survive and can be seen at all is often due to the collectors, especially the ones who grow attached to the small film of modest virtues. They rescue it from a dumpster outside a television affiliate or buy it, sight unseen, in a lot with a few titles they really want. They thread it up and it’s better than they thought. It grows on them. They Perfix it, they Film Guard it. They take it around, talk it up, show it to friends in basements, carefully manage expectations. They’re not handling consumer products with legions of fans, but instead unique objects that passed dimly through schools, rental libraries, civic groups, private people. I think this is the only print, but it should run.

This 16mm collector is, as a species, dying out.

It’s thus one of the most heartening aspects of Cinefest to see this collector carrying on and trafficking in a format forgotten by the very institutions that sustained the small gauge industry. Though the program guide doesn’t often attribute a particular print to a given collector, it’s clear that each film is someone’s prize. Long after video rules the multiplex, these guys will still be running 16mm prints of their favorite films in some dingy, semi-public space. Sixteen may be dead as an amateur and non-theatrical gauge, but there are still guys who roll into town with trunk loads of it. They post notes on the bulletin board: “INTERESTED IN GEORGE ARLISS AND LOUIS WOLHEIM PRINTS. SEE ME—RM. 717.”

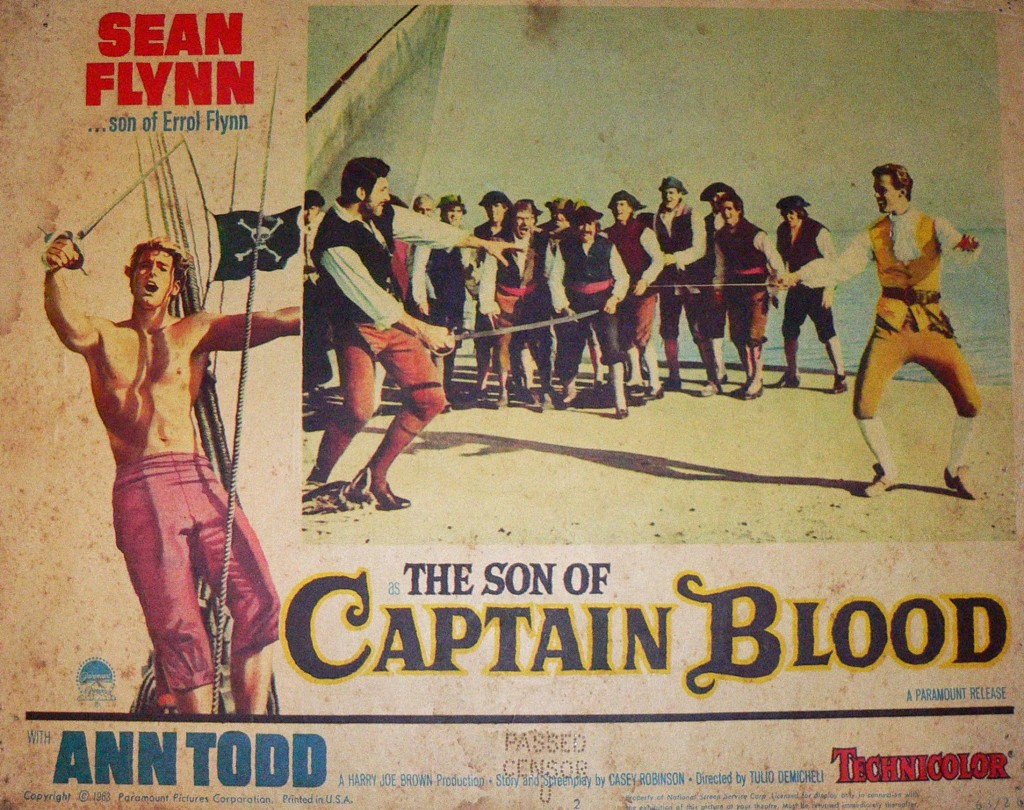

There’s also the dealers’ area—four rooms this year. Truth be told, prints are only offered by a very small contingent of vendors. Lots of DVDs (and home-made DVD-Rs). Rare books at reasonable prices. Paper predominates, with wares ranging from low, low, low to AAA investment. The rules governing market value on one-sheets, inserts, lobby cards, stills, and press books are daunting and complex. Don’t try touching any ’30s original (even, or perhaps especially, for a Monogram western) for less than a few hundred bucks. Louise Brooks and Charlie Chaplin fetch a premium, even in reproduction. Auteurist paraphernalia is surprisingly affordable, with material from such lost causes as Some Came Running, The Tarnished Angels, While the City Sleeps, Party Girl, The Savage Innocents, Underworld, U.S.A., and Avanti! at blowout prices. You might think you know movies, but shuffle through enough boxes of $1 lobby cards and you’ll come across genuine jaw-slackers like The Son of Captain Blood, starring Sean Flynn … son of Errol Flynn.

Budgeting time in the dealers room is a challenge in itself, as films generally run in the main room from nine in the morning to a shade past midnight. Everyone has priorities, but no one wants to miss the annual William J. Burns Detective short. (Made for one season at Educational, the Burns films are the ur-talkies, artifacts even when they were new. Outside of Cinefest regulars, does anyone acknowledge their unsettling existence?) No one sees all the films—or no one should admit to it.

I’m going to concentrate on the pictures about which there is something to say. Many others contained isolated pleasures—the fine art titles of Happiness (1917, Triangle), Gary Cooper’s too-brief nude scene in Wolf Song (1929, Paramount), the battle sequences of What Price Glory? (1926, Fox), a surprisingly youthful and spry supporting turn from Ned Sparks in Love Comes Along (1930, RKO)—but proved otherwise unmemorable. There’s no better way, of course, to learn something deep and detailed about a studio’s style or the dominant practices of a production year than acquaintance with a great many unmemorable pictures.

(I’m also going to refrain from saying anything about Lonesome or Jazzmania, as they were preserved and restored by my employer, the George Eastman House. Having projected the answer prints when they were fresh from the lab, I’m too close to these projects to say anything critical or substantial.)

Forgotten Commandments (1932, Paramount) is a curious artifact in more ways than one. It is primarily an anti-Communist propaganda picture that presents the travails of Paul, a wholesome, almost-American scientist in the university laboratories of Soviet Russia. Paul’s new mentor, Dr. Marinoff (a delectable Irving Pichel, in marked contrast to bland Gene Raymond’s Paul), advocates free love, socialized scientific advancement, and the abolition of Christianity. Anything less is derided as bourgeois. Paul should feel no obligation to his so-called “wife,” but his pursuit of Marinoff’s lover, Marya (lingeried Marguerite Churchill), is something else entirely—and the standard plot ensues.

To be sure, the anti-Western invectives peppered throughout are too narrowly conceived and repetitious to be satirical or insightful in their own right, but this rote aspect is notable: conceived long, long before Hollywood’s golden age of perfunctory Red Scare pictures, Forgotten Commandments sets about, primitively but sincerely, to see whether the revolution in personal relations has rendered the bread-and-butter entanglements of romantic melodrama obsolete.

As narrative and as ideology, Forgotten Commandments strains for feature length. Luckily, Paramount pads out the running time with scenes from DeMille’s silent version of The Ten Commandments, with explanatory voice-over from an earnest, almost-Orthodox priest as he preaches to Moscow’s Dead End Kids in a bombed-out orphanage. The connection to the free love story is tenuous at best. Essentially ransacking the vaults for most every scene from the Biblical prologue of DeMille’s 1923 hit (including, according to Anthony L’Abbate, several alternate takes and camera angles distinct from the surviving version), Forgotten Commandments serves as an index of how low the silent art had fallen by 1932. Presented with its original, now extraneous, intertitles intact, Ten Commandments plays like a disheveled antique—the million-dollar-plus spectacle that thrilled millions reduced to a cheap special effect in a movie that played to a small, small fraction of that. Deemed obsolete junk, it fittingly found its way into another movie that Paramount considered obsolete junk while it was being made. Anyone but the youngest children seeing Forgotten Commandments in 1932 likely harbored fond memories of the DeMille picture—what nerves did reacquaintance touch off?

The co-directors of Forgotten Commandments represent equal parts innocence and experience. William Schorr leaves a scanty paper trail and no other directorial credits. Louis J. Gasnier, meanwhile, as production chief of Pathé’s American office and apparent auteur of The Perils of Pauline and The Exploits of Elaine, literally embodies the silent era almost as fully as DeMille himself. That he here presides over an exhumation of mute spectacle is appropriate and sad. Both are ably assisted (or saved?) by cinematographer Karl Struss, who makes the most out of the recycled sets and the ten-day shooting schedule. An overhead tracking shot through the cardboard cubicles of a communal apartment building is genuinely impressive, as is the uncredited montage that flashes scenes of Marya’s betrayal against shots of the microscopic bacteria that will one day lead the Soviet state.

The Struss touch is also apparent in The Story of Temple Drake (Paramount, 1933), but not to that picture’s credit. Long sought-out by pre-Code fanciers, Temple Drake was dogged by the twin sins of intense salaciousness (there was no way this one would or could be re-cut for Code approval or television distribution after the fact) and a complicated rights situation (it was eventually re-made at Fox, which presumably controlled Temple Drake thereafter). It used to screen exclusively via 16mm collectors’ prints and VHS bootlegs, and even then, rarely and surreptitiously. The Museum of Modern Art recently made a sparkling 35mm print from nitrate elements, but Temple Drake has the same problems in 35 that it did in 16.

Never less than visually stunning, but also never more than just pretty, this neutered Faulkner adaptation (of Sanctuary) barrels along without recourse to subplots or social color. A threadbare moral test foisted upon Miriam Hopkins’s spoiled scion slut, Temple Drake is dramatically and psychologically prosaic, with all sexual transgressions provoking guilt and second-hand shock. Explicit or not, the dynamics are effectively those of stage conventions from two or three decades before, done up with much gloss but little imagination or feeling. The suggestive scene of Hopkins writhing in a ditch filled with corn cobs before her (mostly off-screen) rape is a veiled reference to the rather more explicit situation in Faulkner’s novel, which itself provoked an ugly strain of tittering in the theater. (Pre-Code pictures tend to attract an out-sized amount of hipster gawking, though the Cinefest audience is hardly hipster.)

Temple Drake is ultimately ill-at-ease with itself, tripe-trash with half-sincere misgivings. Much more interesting—and genuinely sexy—is the Lubitsch-directed “Origins of the Apache” number with Maurice Chevalier and Evelyn Brent from Paramount on Parade (1930), which was featured in Richard Barrios’s “A Song in the Dark” clip show, so named after his book on the history of the early musicals. Unfussily staged and never over-pleased with itself, this gem is just verbal jousting ending with a suggested striptease, but, like The Love Parade and The Smiling Lieutenant, it conveys a complicated understanding of and respect for desire while Temple Drake skims the surface and makes some naughty faces. (KW)

To be continued…

For more information on Cinefest, the Syracuse Cinephile Society, and their weekly Monday night series at the Spaghetti Warehouse (!), please visit their website: http://www.syracusecinephile.com/