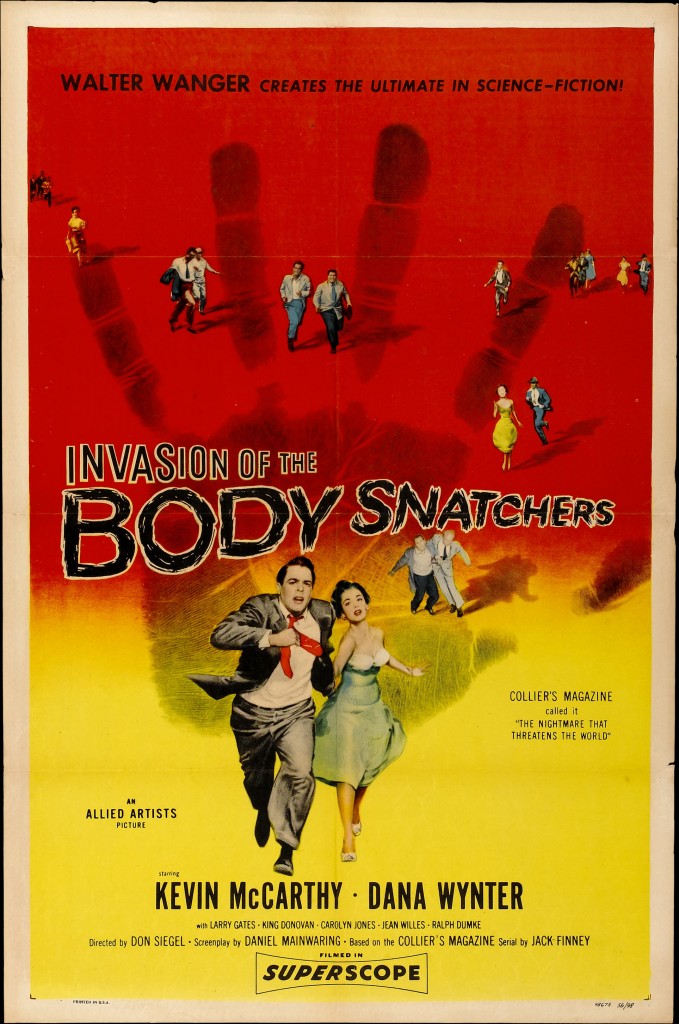

This week’s feature, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, has long been regarded as a political hot potato. Like High Noon, it’s either a preachment for vigilance in the face of a Communistic menace or a cautionary allegory of a conformist overreaction to that selfsame menace. But for a certain kind of cinephile, the aspect ratio of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is just as contested as its ideological underpinnings. Moviegoers shouldn’t be passive pods for received wisdom, so we thought it would be edifying to discuss the context of theatrical exhibitions in the 1950s and beyond. – Eds.

This week’s feature, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, has long been regarded as a political hot potato. Like High Noon, it’s either a preachment for vigilance in the face of a Communistic menace or a cautionary allegory of a conformist overreaction to that selfsame menace. But for a certain kind of cinephile, the aspect ratio of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is just as contested as its ideological underpinnings. Moviegoers shouldn’t be passive pods for received wisdom, so we thought it would be edifying to discuss the context of theatrical exhibitions in the 1950s and beyond. – Eds.

The shape and configuration of theatrical film has been basically unchanged since the earliest days of the twentieth century—35mm in width, four uniform perforations per frame. The relative apportionment of image and sound within that frame has changed tremendously, however, and projectionists have long been expected to extract images of all shapes and sizes from the same old film strip. Through a combination of specialized lenses, lens attachments, aperture plates, and screen masking, they present a range of rectangular images known in industry parlance as aspect ratios.

These shapes are expressed in numeric terms, as a ratio of image width to image height. The common aspect ratio 1.37:1, for example, means that the image on screen is 1.37 times wider than it is high. Counterintuitively, many of the wider aspect ratios like 1.85:1 achieve this apparent horizontal superiority simply by artificially constricting the height of the frame; since we’re talking in ratios rather than absolutes, cropping the top and bottom from the frame does yield a wider image, albeit with some loss of clarity when blown up on an enormous theater screen. The ultra-wide Cinemascope—2.39:1—uses a two-piece lens to anamorphically stretch a heavily compressed image on a conventional film strip.