Get updates and see more images from this project via Instagram!

Submissions welcome, send to: info@chicagofilmsociety.org

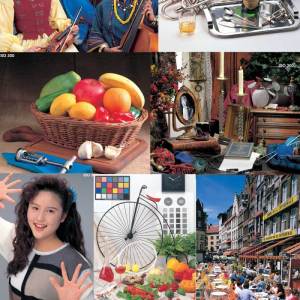

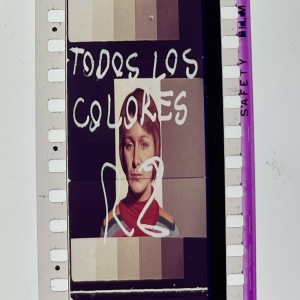

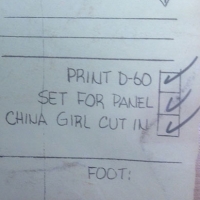

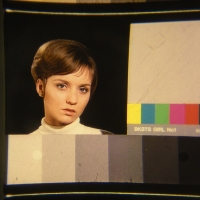

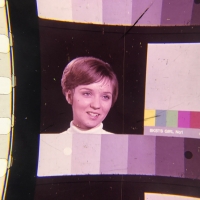

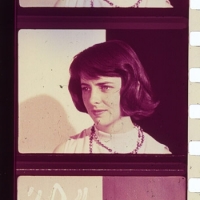

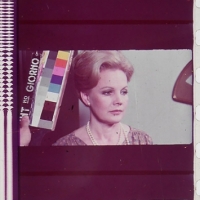

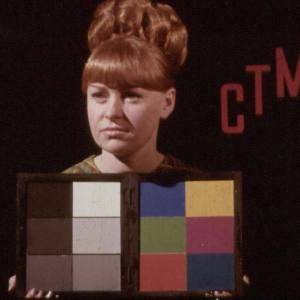

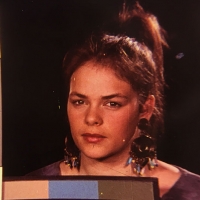

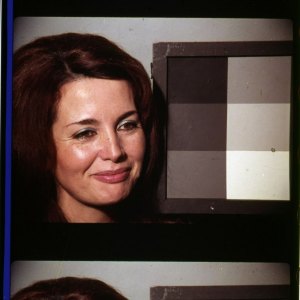

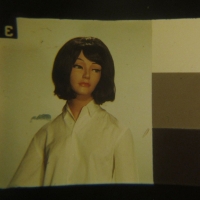

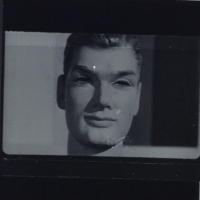

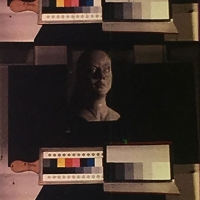

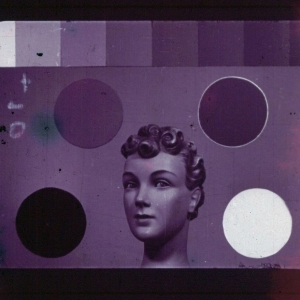

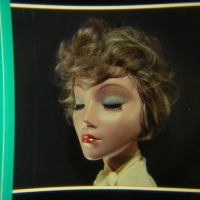

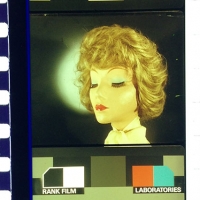

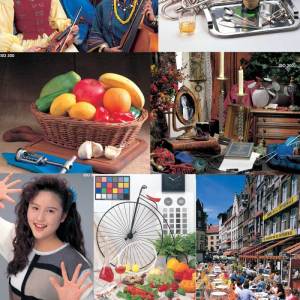

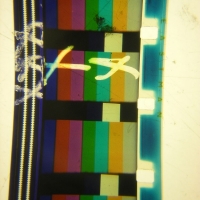

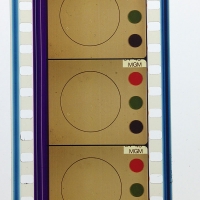

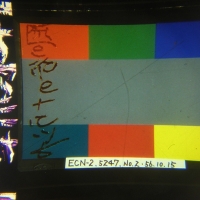

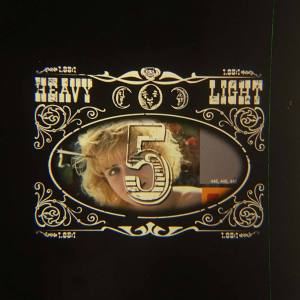

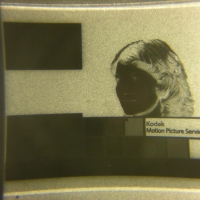

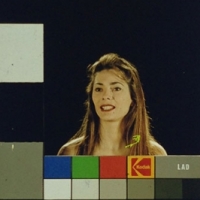

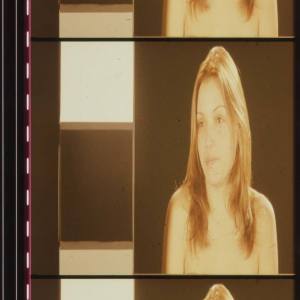

Started in 2011, the Leader Ladies Project presents a collection of “China Girls” (or “Leader Ladies,” as we’ve heard at least one person call them) – the test images of (most often) women that sometimes appear in the countdown that begins every reel of motion picture film meant for exhibition, often accompanied by color bars and gray patches. Their images were used by film lab workers setting color timing or black and white density – and they were sometimes film lab workers themselves. These images are a mix from-the-rewind-bench snapshots we’ve taken ourselves, as well as scans and photos from archivists, projectionists, and film collectors from around the world. Normally not visible to anyone outside a fairly small subset of the film industry, this is the largest publicly viewable collection in the country.

The origin of the term “China Girl” is debated, but theories abound. One popular theory connects the term to a “Chinese-style” garment (most often a colorful shirt) worn by the model in some test frames. Another suggests that early test frames used porcelain (“china”) mannequins instead of live women. Regardless of origin, “china girl” is by far the most common American term for them. (Others recorded include “lady wedge”, “china doll”, “girl head”, and “leader lady”). In France, they’re called “Lili,” perhaps after the traditional name of the slate used in Technicolor shoots.

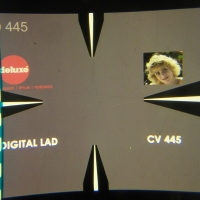

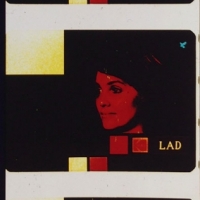

Whatever you call them, their presence on the film (secretly sharing space with Hollywood’s starlets) is a fleeting visual document of the film industry’s vast off-screen labor pool. They remind us that every film made on film stock has a physical history, that each print we encounter in the projection booth, or projected onto the screen from the audience (or reproduced digitally on a laptop screen) passed through the hands of lab workers and technicians before it came to us. (In fact, the creator of the successor of the traditional China Girl, the “LAD Girl” – pictured below – won an Oscar in 2001 for his work. His acceptance speech can be seen here, and an excerpt can be read just above the image gallery).

The most substantial study of “China Girls” that we know of was assembled by Julie Buck and Karin Segal at the Harvard Film Archive in 2006. Write-ups of their exhibition of frame restorations can be read here, and details on various other projects and exhibitions can be found here. They also used their work to assemble a wonderful short subject called “Girls on Film“. A similar French exhibition in 2009 also produced a short subject, which included some stunning examples we have never seen on this side of the Atlantic. Genevieve Yue’s 2020 book “Girl Head: Feminism and Film Materiality” is a fascinating study that explores role of gender and race in film production processes, including a history of the China Girl.

A very special thanks to all the people who have submitted images to us over the years. Projectionists, archivists, film collectors, or just people who love film. Their names and organizations appear in the image captions.

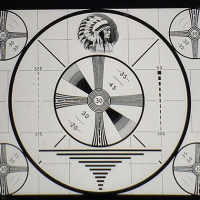

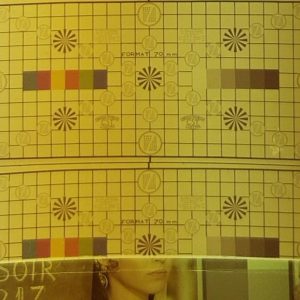

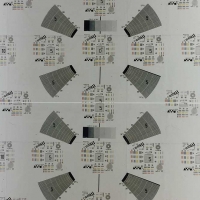

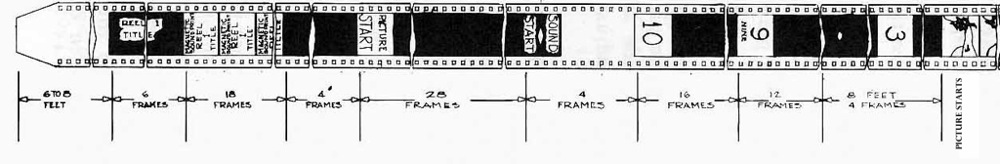

Here is a diagram of typical film head leader. “China Girls” usually appear somewhere between the “10” and the “3” shown in the countdown below (though they appear elsewhere as well).

Have your highlights lost their sparkle?

And the midtones lost their scale?

Are your shadows going smokey?

And the colors turning stale?

Have you lost a little business to labs whose pictures shine?

Because to do it right – takes a lot of time.

Well, here’s a brand new system. It’s simple as can be!

Its name is LAD – an acronym for Laboratory Aim Density.

– John P. Pytlak

A brief explanation of how China Girls are used in the lab:

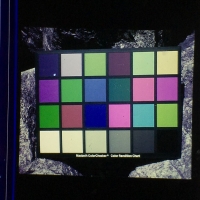

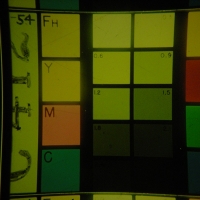

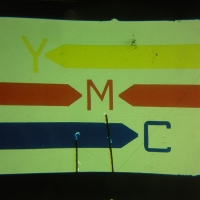

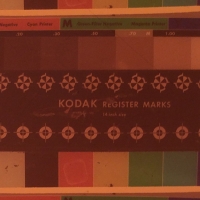

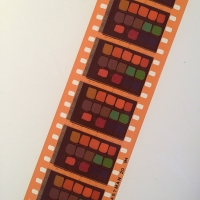

“Typically, complete reels of a china girl were shot on camera negative either by Kodak or the lab itself – to a very tight standard of exposure and processing. Once a film was shot and edited, a few frames of the china girl would be cut into the head leader of the film. Then when any print was being made from the negative, the china girl could be used as a colour control reference. Printing and processing film is a complex set of optical and chemical steps, and it’s easy for the colours to shift from one copy to the next: by including a known standard image, lab QC technicians could take densitometer readings of the grey squares, and also make a visual assessment of the facial flesh tones to determine if the print was within tolerance. This is obviously more objective and consistent than judging any scene in the film, which might have been shot or graded deliberately dark, or reddish etc. for story-telling purposes.

Different labs may have used different techniques to produce their stocks of chinagirl. The ones that I produced for our lab (Colorfilm) a long time ago were shot in a studio under very precise conditions, aiming at a very precise density on the grey card. I wouldn’t have risked any variation in outdoor light over a lengthy shoot (we shot several reels in one batch) as obviously every frame must be absolutely identical in colour and density.”

— Dominic Case (Former technical manager at Colorfilm, Atlab and Deluxe, a few of the images Dominic designed can be found in the gallery below.

An excerpt from “Girl Head” (Genevieve Yue, 2020)

“From one perspective, the China Girl is an analytic tool equivalent to test patterns, color swatches, and other instruments used in quality control procedures. Its appearance is only incidental to its function, which was rendered minimal by the late 1970s. From another perspective, the China Girl is a suggestive image, and however depersonalized, it still carries a charge of personal significance, even of life. Though laboratory technicians will often cite the former as the rationale for using the China Girl, it is the latter that accounts for its persistence. Film too, is often conceived in terms of this contradiction: both a mass-produced object and an image imbued with and organically underpinned by a quality of life.”

Recent Additions:

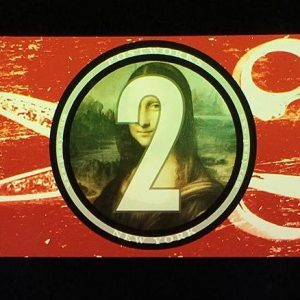

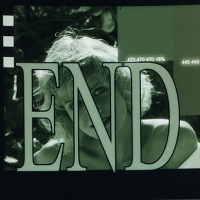

LEADER LADIES GALLERY:

Click Image to Enlarge & Read Captions

Artificial Leader Ladies:

Color Bars,Charts, & Countdown:

Kodak LAD Lady Variations: