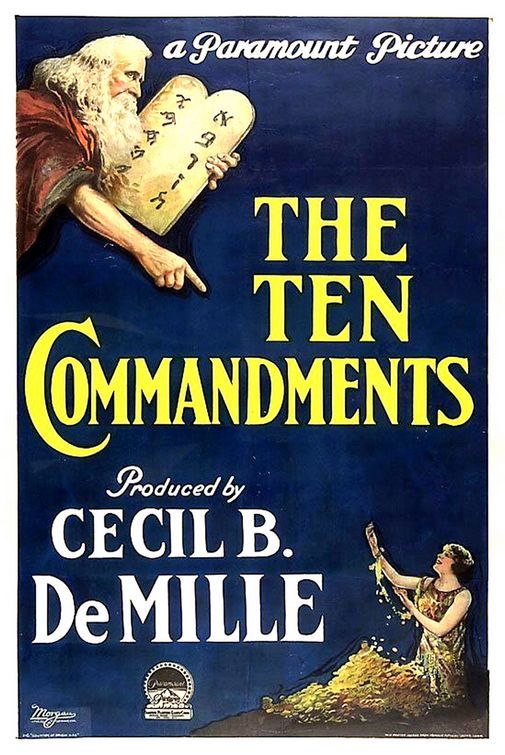

Tonight we’ll be screening an original IB Technicolor 35mm print of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments at the Portage. This 1956 epic is unequalled in its elemental power—its confusing mix of knotty, alien carnality and religious fervor has rightly frightened generations of children. (It’s also sufficiently iconic and hip enough to earn a nod in Arnaud Desplechin’s recent A Christmas Tale, alongside Nietzsche and Blackalicious.) But this four-hour spectacle wasn’t DeMille’s first attempt at bringing the Exodus to the screen. As a prologue to tonight’s festivities, we’re presenting a lengthy account of DeMille’s 1923 version. (To put that in some perspective, Charlton Heston was born in 1923.) Written in 2008, but previously unpublished, we hope you enjoy this article. And remember: You cannot break the Ten Commandments—they will break you. – Ed.

Tonight we’ll be screening an original IB Technicolor 35mm print of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments at the Portage. This 1956 epic is unequalled in its elemental power—its confusing mix of knotty, alien carnality and religious fervor has rightly frightened generations of children. (It’s also sufficiently iconic and hip enough to earn a nod in Arnaud Desplechin’s recent A Christmas Tale, alongside Nietzsche and Blackalicious.) But this four-hour spectacle wasn’t DeMille’s first attempt at bringing the Exodus to the screen. As a prologue to tonight’s festivities, we’re presenting a lengthy account of DeMille’s 1923 version. (To put that in some perspective, Charlton Heston was born in 1923.) Written in 2008, but previously unpublished, we hope you enjoy this article. And remember: You cannot break the Ten Commandments—they will break you. – Ed.

• • •

“Intolerance unfortunately was the picture really that broke [Griffith], because he made a dramatic error that should never be made,” remarked Cecil B. DeMille in 1958. “He told four stories under the guise of one, and consequently all four failed. Because that is a formula that so far as I know has never been successful on the stage. One-act plays can be successful but not … the same theme running through four separate stories as one play.” DeMille himself never made any film as structurally ambitious as Griffith’s masterwork but his first rendition of The Ten Commandments perhaps comes closest. Intrinsically bifurcated rather than mosaical, DeMille’s 1923 super-production nevertheless stands as one of the very few Intolerance descendants to seriously attempt anything resembling Griffith’s thematic integration of parallel spectacles.

DeMille embarked on his own ‘dramatic error’ after a string of failed pictures. The latest of them, Adam’s Rib, struck many critics as another unnecessary entry in that most frivolous of genres, the high-society marital farce, which DeMille had practically created in 1918 and had been more or less confined to working in ever since by the Famous Players-Lasky front office. Meanwhile epic pictures from Fairbanks’s Robin Hood to Universal’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame were brought to the screen in hopes of sating a public primed for expensive costume spectacles by German imports such as Lubitsch’s Madame DuBarry. Famous Players-Lasky even had the effrontery to let James Cruze, then a relative neophyte, spend $782,000 on The Covered Wagon while forcing its star director to hew to a formula of diminishing appeal. Unlike Griffith, DeMille’s screen career began with and paralleled the development of the feature, his name practically synonymous with a certain notion of middle-class entertainment. Producers everywhere now laid claim to an audience that DeMille had nurtured. DeMille insisted on entering the million-dollar picture race himself, which would mean working on a scale he had not been permitted since Joan the Woman of 1916.

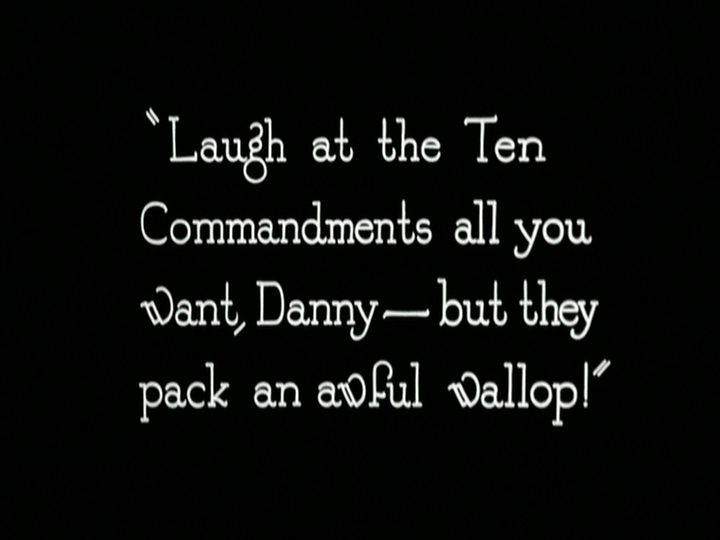

To make especially sure that his next picture would strike a chord with audiences DeMille made the unusual maneuver of soliciting scenarios directly from the public through a contest in the Los Angeles Times. Among thousands of submissions, DeMille was particularly taken with that of one F. C. Nelson, Lansing, Michigan, lubricant manufacturer: “You cannot break the Ten Commandments—they will break you.” For that line Nelson won a thousand dollars.

To make especially sure that his next picture would strike a chord with audiences DeMille made the unusual maneuver of soliciting scenarios directly from the public through a contest in the Los Angeles Times. Among thousands of submissions, DeMille was particularly taken with that of one F. C. Nelson, Lansing, Michigan, lubricant manufacturer: “You cannot break the Ten Commandments—they will break you.” For that line Nelson won a thousand dollars.

Seven other entrants also suggested a Commandments picture and each received comparable compensation, but it was Nelson’s phrasing that had the strongest influence on DeMille’s conception of The Ten Commandments. Late in the film an intertitle reprints Nelson’s injunction, but his sense of vernacular bluntness hangs over the whole enterprise.

At first DeMille instructed his regular scenarist Jeanie Macpherson to translate Nelson’s dictum into a string of parables, each one illustrating the consequences of breaking one or perhaps two Commandments. When that structure proved unsatisfactory Macpherson concocted a convoluted scenario in which one emblematic modern man violates all ten. That was better but something was still missing.

“‘Seeing is believing,’” recounted Macpherson, “and we believed the spectator would be much more impressed with a story based on the Commandments if he first had seen the history of them, how they were given and what effect they had upon the people who had come in contact with them during that far-away time of the birth of the Decalogue, than as if this spectator had merely a vague memory from far off Sunday-school days that somewhere at some time the Ten Commandments had been given to somebody.”

No viewer of DeMille’s version would fail to recollect the story of the Lawgiver. Whether Adolph Zukor or Jesse Lasky knew it or not, no expense would be spared in the commission of this holy spectacle. “I cannot and will not make pictures with a yardstick,” DeMille told Zukor, though neither was shy about releasing the following statistics for purposes of ballyhoo: the Exodus was recreated in Santa Barbara’s Guadalupe sand dunes with the labor of 500 carpenters, 400 painters, and 380 decorators. The construction of the entrance to Rameses’s city required 300 tons of plaster, 55,000 board feet of lumber, and 25,000 pounds of nails. Costumes used 16 miles of cloth. The scenes themselves would require some 3,000 animals and 2,500 extras, including a smattering of Orthodox Jews to lend authenticity. The cast and crew lived out of a tent city that measured 24 square miles, with two mess halls, 125 chefs, and 10 tons of hay consumed by the livestock on a daily basis. Communication was facilitated by an extensive army field telephone system, the largest of its kind used since the Great War.

(Considering the scale of the production, the trick photography marshaled to achieve the parting of the Red Sea was rather modest: technical director Roy Pomeroy devised a traveling matte system that allowed the Jews to march across the seafloor between two wavering mountains of gelatin.)

(Considering the scale of the production, the trick photography marshaled to achieve the parting of the Red Sea was rather modest: technical director Roy Pomeroy devised a traveling matte system that allowed the Jews to march across the seafloor between two wavering mountains of gelatin.)

The Ten Commandments had no less than six cinematographers—four credited technicians along with additional inserts by famed photographer Edward S. Curtis and color footage by Ray Rennahan. His employer, the Technicolor Motion Picture Corporation—which had already released its own feature, The Toll of the Sea, through Metro—hoped to induce more Hollywood producers to utilize their two-color system. They offered Rennahan’s services on ridiculously generous terms: if DeMille liked the footage, he could use it in the picture gratis and if he did not it would be destroyed. Though DeMille preferred the more artisanal (and expensive) look achieved by the Handschiegl stencil process, he could not refuse Technicolor’s deal and agreed to let Rennahan shoot the Exodus and the parting of the Red Sea. (Release prints included the Handschiegl footage, the Technicolor footage, or some assortment of both, though the Technicolor version was predominant.)

By this time DeMille’s profligacy had well exceeded that of Cruze, whose western saga had already settled into a very profitable eight-month run in Hollywood. DeMille agreed to waive his guarantee but insisted on his keeping his weekly salary. Neither this gesture, nor DeMille’s promise that The Ten Commandments would be “the biggest picture ever made, not only from the standpoint of spectacle but from the standpoint of humanness, dramatic power, and the great good it will do,” much assuaged Zukor, who seriously contemplated selling the negative back to DeMille and forfeiting Paramount’s stake in any profits for a million dollars. Lasky prevailed upon him, however, and DeMille went forward with location shooting in San Francisco for the modern story. The final cost was $1,475,836.93. To remain solvent in light of that sum, Famous Players-Lasky shut down all other productions from October 1923 to year’s end.

Early reaction in the industry was overwhelmingly positive. Lasky himself lauded “the sincerity with which Cecil has handled this tremendous subject … almost as if he were inspired, a new and much bigger Cecil DeMille.” This theme was repeated by Motion Picture Magazine: “Just when humorists were finding in the DeMille tales of distorted society life ample material for their somewhat mordant jesting, he comes forth and blazes his name on the roster of the great.” Moving Picture World echoed that sentiment, too, proclaiming that “[e]very member of the large cast gives an excellent performance and all seem to be imbued with the bigness of the theme.” At Photoplay James Quirk went further still: “The best photoplay ever made. The greatest theatrical spectacle in history. The greatest sermon on the tablets which form the basis of all law ever preached. Strong words, indeed, but written two weeks after seeing it, after serious consideration of Griffith’s Intolerance and The Birth of a Nation. It will last as long as the film on which it is recorded.”

Early reaction in the industry was overwhelmingly positive. Lasky himself lauded “the sincerity with which Cecil has handled this tremendous subject … almost as if he were inspired, a new and much bigger Cecil DeMille.” This theme was repeated by Motion Picture Magazine: “Just when humorists were finding in the DeMille tales of distorted society life ample material for their somewhat mordant jesting, he comes forth and blazes his name on the roster of the great.” Moving Picture World echoed that sentiment, too, proclaiming that “[e]very member of the large cast gives an excellent performance and all seem to be imbued with the bigness of the theme.” At Photoplay James Quirk went further still: “The best photoplay ever made. The greatest theatrical spectacle in history. The greatest sermon on the tablets which form the basis of all law ever preached. Strong words, indeed, but written two weeks after seeing it, after serious consideration of Griffith’s Intolerance and The Birth of a Nation. It will last as long as the film on which it is recorded.”

Any sympathetic account of the picture has to engage with the context from which it emerged. The 1922 rediscovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb had touched off immense popular interest in all things Egyptian, so much so that the Los Angeles Times printed an Egyptologist’s critique of DeMille’s film that alleged that, as the historical record was concerned, Rameses was the ‘Wrong Pharaoh’ for the Exodus saga. More significant, however, was the emergence of a new brand of evangelical Christianity in America, exemplified in the figure of Aimee Semple McPherson, who embodied many contradictions not dissimilar to DeMille’s own. McPherson brought that most ‘old time’ of all religious denominations—Pentecostalism, including speaking in tongues and faith healing—into the Hollywood mainstream, dressing like a starlet and delivering sermons in the form of elaborate production numbers that rivaled the proscenium prologues of the big picture houses. The passion play was quickly being replaced by a less anti-Semitic, inherently more ecumenical form of mass religious address with the aesthetics of Hollywood and the Holy Land converging into one unbeatable box office formula. (DeMille’s own King of Kings would go even further in this respect.)

For his part DeMille apparently subscribed to a kind of Millenarianism that elegantly dovetailed with the promotion of his latest picture: “The world is eagerly awaiting a universal religion. The time is ripe for a greater and truer religious understanding…The world is weary of creeds, dogmas, forms, rituals, and isms, but it finds that without religion it is like a ship without a rudder…. Religion does not need to be clothed in the garment of Confucianism, Buddhism, Christianity, Mohammedanism or any other set form of worship. The principles of all are the same. Look up the covenants of each, and you will find the essentials of the Ten Commandments of the Mosaic law.”

Some journalists, particularly those at the newspaper that had sponsored DeMille’s scenario gambit, found that C. B.’s new film agreeably cut through much doctrinal dross. One Los Angeles Times columnist opined: “I wonder if there is any religious creed or cult that is based strictly and exclusively upon the Ten Commandments … As those Ten Commandments are flashed in mighty forcefulness direct from Heaven in the film story, one is conscious of amazed surprise at their straight-forward simplicity…. There isn’t a word about prohibition, gambling, dancing, smoking, women’s clothes, divorce, prize fights, card-playing, evolution, nudity, or any of those bitterly controversial subjects that occupy so much attention from some pulpits.”

Some journalists, particularly those at the newspaper that had sponsored DeMille’s scenario gambit, found that C. B.’s new film agreeably cut through much doctrinal dross. One Los Angeles Times columnist opined: “I wonder if there is any religious creed or cult that is based strictly and exclusively upon the Ten Commandments … As those Ten Commandments are flashed in mighty forcefulness direct from Heaven in the film story, one is conscious of amazed surprise at their straight-forward simplicity…. There isn’t a word about prohibition, gambling, dancing, smoking, women’s clothes, divorce, prize fights, card-playing, evolution, nudity, or any of those bitterly controversial subjects that occupy so much attention from some pulpits.”

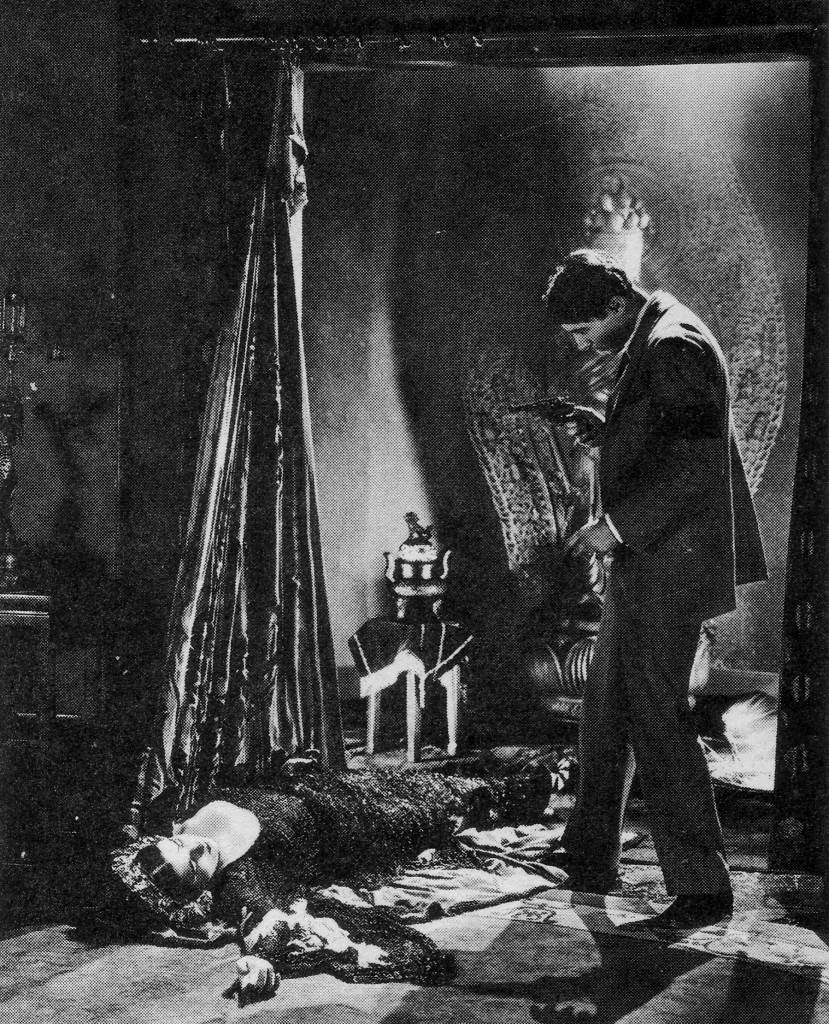

Precisely by ignoring these contemporary concerns and focusing instead on Technicolor, tumbling jute cathedrals, and Franco-Chinese leprosy-carrying vamps did The Ten Commandments become the quintessential frivolous-sincere expression of spirituality in Coolidge-era America. It might have earned its costs back on that basis alone, but DeMille and Paramount could not have taken such a risk.

Zukor was still bitter about the cost overruns, a fact reflected in the virtual absence of The Ten Commandments from the firm’s trade paper ads, leaving outfits like Simplex and Technicolor to tout their affiliation with the project in their own full-page spreads. That spite did not spill over to the film’s public profile. Zukor signed off on a quarter-million dollars’ worth of accoutrements for the film’s 21 Dec 1923 New York premiere at the George M. Cohan Theatre, which included much Egyptian lobby décor and two screen-sized tablets that flew open like stone curtains at the start of the picture. At the end of its 36-week run at the Cohan, The Ten Commandments moved to the Criterion, which had recently hosted 59 weeks of The Covered Wagon.

Zukor was still bitter about the cost overruns, a fact reflected in the virtual absence of The Ten Commandments from the firm’s trade paper ads, leaving outfits like Simplex and Technicolor to tout their affiliation with the project in their own full-page spreads. That spite did not spill over to the film’s public profile. Zukor signed off on a quarter-million dollars’ worth of accoutrements for the film’s 21 Dec 1923 New York premiere at the George M. Cohan Theatre, which included much Egyptian lobby décor and two screen-sized tablets that flew open like stone curtains at the start of the picture. At the end of its 36-week run at the Cohan, The Ten Commandments moved to the Criterion, which had recently hosted 59 weeks of The Covered Wagon.

The Hollywood premiere of “DeMille’s ultra-drama of the ages,” conveniently held at Grauman’s Egyptian on 4 Dec 1923, boasted some 300 Lasky celebrities and a stage show, “A Night in Pharaoh’s Palace.” As the picture’s seven-month run wore on “Pharaoh’s Palace” purportedly drew as many spectators as the feature itself. This prologue to a prologue, copyrighted by Sid Grauman, was seized upon by Paramount as an example for other big houses to emulate, filming its last performance for that very purpose. Attendees of the 350th screening of The Ten Commandments at Grauman’s received miniature bronze replicas of Moses’ tablets.

The road show continued with a touring twenty-piece orchestra that played Hugo Riesenfeld’s score at every performance. Eighteen weeks at Chicago’s Woods. Fourteen at Philadelphia’s Aldine. The initial three-week engagement in Washington, D.C. was expanded to five; the National was still doing capacity business when it had to pull the picture to make way for a long-standing booking of Music Box Revue. “It is realized,” noted the Washington Post, “that the De Mille epic is not a movie super-special of the kind that plays a flock of neighborhood houses directly [after] the “key” run at a downtown theater is concluded. In fact, no version of The Ten Commandments will be put into movie houses for many months to come.” The Ten Commandments did not return to the capital until 1926!

International screenings proved similarly strong and equally ham-fisted. The Prince of Wales and the royal family purportedly attended the picture more than once during its 250-performance London engagement. Australian exhibitors hoping to present The Ten Commandments faced stiff contracts that stipulated an American-style publicity campaign. Eleven road shows toured the continent; each came with a Paramount agent who would spend two weeks in a given territory prior to the premiere, rustling up media coverage and recruiting locals to perform in the “Grand Atmospheric Egyptian Prologue.”

Skeptics emerged. A Presbyterian church board member of St. Paul, Minnesota, related that “When I saw the first [half] of this photoplay I said to myself I would like to show it to my Sunday school class. But when I saw the second half I said it wouldn’t do.” One rogue Los Angeles Times correspondent who attended a New York screening noted “[t]he audience was wildly enthusiastic over the colored photography so who am I to say that it looked to me like a geographical case of measles. Throughout the biblical sequence the enthusiasm ran high but the modern story did not go over so well.” ‘Mae Tinée,’ the composite critic at the Chicago Tribune, reprimanded DeMille for a complicated two-part structure and then delivered the ultimate blow: “As in Intolerance one suspects the average picture-seer will leave the theater after having seen this production asking aloud or otherwise: ‘What’s it all about, anyways?’”

Skeptics emerged. A Presbyterian church board member of St. Paul, Minnesota, related that “When I saw the first [half] of this photoplay I said to myself I would like to show it to my Sunday school class. But when I saw the second half I said it wouldn’t do.” One rogue Los Angeles Times correspondent who attended a New York screening noted “[t]he audience was wildly enthusiastic over the colored photography so who am I to say that it looked to me like a geographical case of measles. Throughout the biblical sequence the enthusiasm ran high but the modern story did not go over so well.” ‘Mae Tinée,’ the composite critic at the Chicago Tribune, reprimanded DeMille for a complicated two-part structure and then delivered the ultimate blow: “As in Intolerance one suspects the average picture-seer will leave the theater after having seen this production asking aloud or otherwise: ‘What’s it all about, anyways?’”

DeMille disagreed. Defending Macpherson’s scenario as ‘Euripidean,’ he speculated that those who applauded the prologue but maligned the modern story “probably somewhere on their mental horizon have been affected far more than they knew, not by the actual Red Sea catastrophe, but by its modern prototype, the scenes where a single man is just as surely destroyed by a mental and emotional Red Sea.”

Engulfed, uncomprehending, or otherwise stupefied, picturegoers continued to flock to The Ten Commandments, which topped exhibitors’ polls as the most popular attraction of 1924 and 1925. More dangerous than tepid critical reaction was the very real antipathy towards DeMille on the part of Zukor and other Paramount executives. Though this holy folly eventually grossed an impressive $4,169,798.38, DeMille found himself confined to cheaper programmer pictures throughout 1924. Unhappy with material like The Golden Bed, DeMille formed his own independent company when his Paramount contract expired in 1925—by which time M-G-M’s six-million dollar bill for Ben-Hur made DeMille’s extravagance look like a pittance. With some not insignificant exceptions, the remainder of his career would be devoted to films rather more in the mold of the Ten Commandments prologue than that of the modern story.

By 1932, however, DeMille was back at Paramount, which had recently used his 1923 footage to bring a ten-day anti-Bolshevik quickie called Forgotten Commandments up to feature length. Not content to see his great achievement made obsolete by the talkies, DeMille eventually remade the picture in 1956 as a four-hour, entirely Biblical Vistavision blockbuster. For the second time in the studio’s history The Ten Commandments emerged as Paramount’s most expensive venture to date.